Share and Follow

Brown describes the site as “virtually a concentration camp for the old people”.

“I’ve had spiritual things happen to me here, and I’ve had the old people come and visit me while I’ve been here.

When you walk around, you feel a lot of sadness here too. There’s only certain places I’ll go on this property because of that reason.

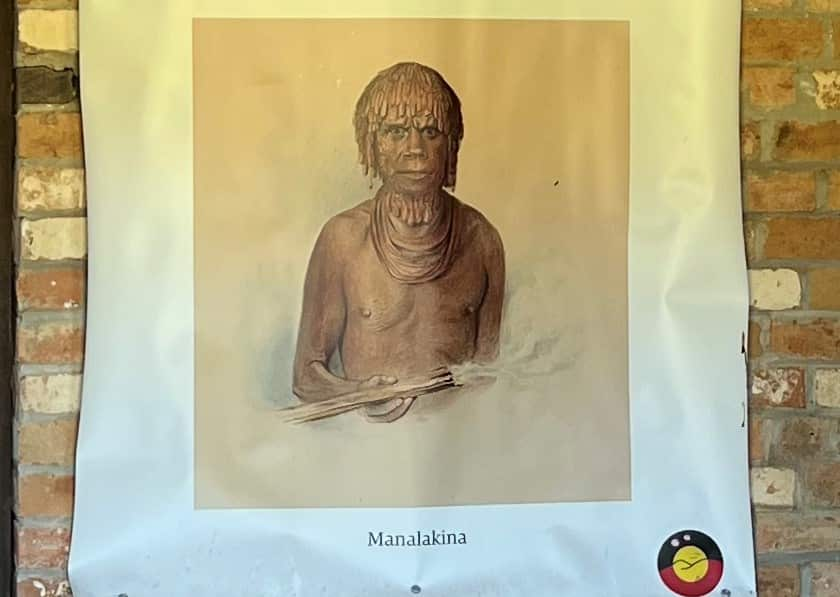

Manalakina was among many Tasmanian Aboriginal people who would ultimately die at Wybalenna.

Who was Manalakina?

Manalakina was a chief of the north-east nations and one of the only chiefs to survive the British invasion of Lutruwita — the palawa kani word for the main island of Tasmania — and the subsequent war.

A watercolour portrait of Manalakina by Thomas Bock sits inside the door of the Chapel at Wybalenna. Source: SBS News / Kerrin Thomas

From the beginning of the invasion in 1803, the British dispossessed Aboriginal people of their lands, took some captive and slaughtered hundreds more. The conflict peaked between the mid-1820s and early 1830s in what became known as the Black War.

Manalakina was used by Robinson to find more Aboriginal people, and when he came to Wybalenna, Manalakina realised he’d been betrayed: The treaty he thought had been negotiated had been broken. Instead, his people had been effectively imprisoned on the island to be “civilised and Christianised”.

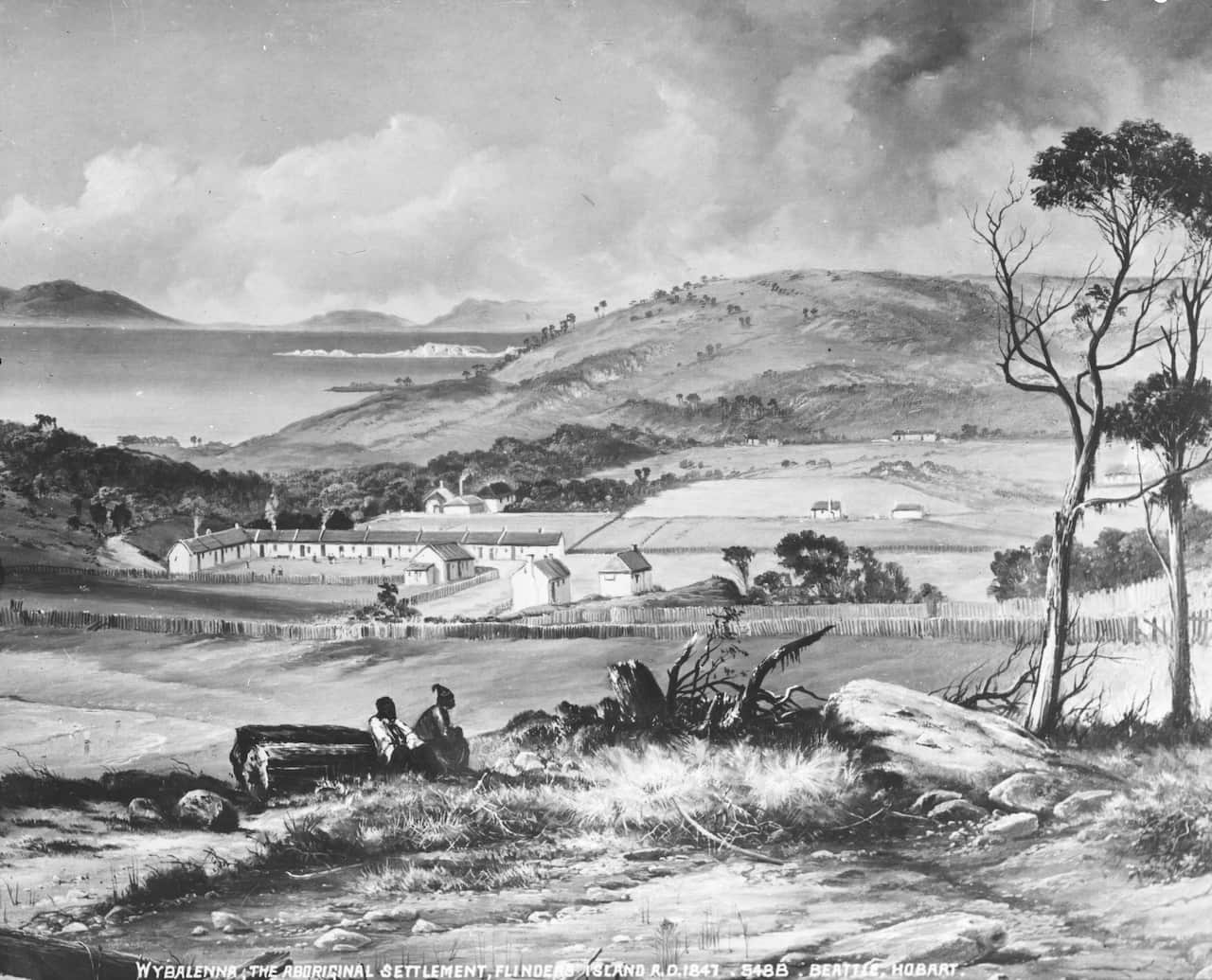

An early print of Wybalenna with various buildings, including the chapel and L-shaped Aboriginal residences. Credit: Tasmanian Archives NS1013/1/570

After surviving 30 years of invasion, he lived for around three years at Wybalenna before his death in 1835, never returning to his home country.

“He was brought here and made promises to and the promises were broken and he shaved his hair off and became a broken man.”

The legacy of Wybalenna

The cemetery at Wybalenna contains 107 confirmed but unmarked burial sites. The location of many others remains unknown.

A sign details the 107 known burials in the cemetery on Wybalenna with the unmarked graves beyond. Source: SBS News / Kerrin Thomas

Pakana woman and general manager of the Aboriginal Land Council of Tasmania, Sarah Wilcox, says, despite a lack of awareness among the broader Australian population, the site holds great significance.

“It was a place that was recognised when the term genocide was penned [in the 1940s], referring to the Tasmanian Aboriginal people.”

Land handback

“A big mob of us came from Cape Barren and there was a heap of locals here from Flinders. We all sat here and stayed here, occupied the place and took the place back.”

There are places on Wybalenna Brendan ‘Buck’ Brown won’t go. Source: SBS News / Kerrin Thomas

Wybalenna spans an area of almost 140 hectares on the west coast of Flinders Island and includes a homestead, chapel and graveyard, as well as an old shearing shed used until the 1970s by a previous owner, which has been repaired and has basic kitchen facilities.

“The generosity through those donors and those sponsors we’ve been able to get over time has been overwhelming for us. It’s an incredible and humbling experience in a way,” she says.

Healing and truth-telling

The work started under former Land Council manager, Rebecca Digney, who handed over the reins to Wilcox in June.

“Wybalenna is definitely a place that conjures up a variety of feelings. It’s one of great sadness; it can feel quite desolate at times. But also, it’s a good reminder of what my people have been through and how strong they are.

Our cultural practices continue – despite the attempts to Christianise our people here, our people survived against all odds, and we continue as a strong and vibrant community today.

“Also for families, so our younger generations and future generations understand the significance of that place.”

The chapel at Wybalenna is a “monument to the horrors” that occurred there as colonial officials sought to Christianise the Tasmanian Aboriginal people. Source: SBS News / Kerrin Thomas

The work so far has focused mostly on the Aboriginal community’s experience at the site.

“It’s a great opportunity for people to learn, to listen, to understand and to absorb that truth.”

NAIDOC commemorations

“It speaks to the leadership and strength within our community, past, present, and future,” he told attendees.

A flag-raising was held at Wybalenna to mark the start of NAIDOC Week 2025. Source: Supplied / Aboriginal Land Council of Tasmania

“Truth-telling at Wybalenna most certainly acknowledges the true story and legacy for our old people here at Wybalenna, it also shows the strength of our community with our continuing fight to have our stories told and vision for our community with the interpretations and works here at Wybalenna.

“It is a sad place, but at the same time it’s important that we’re here to take back that sense of pride at this place and honour our people.”

Wybalenna has been described by some as a desolate place, but it is also a place for truth-telling. Source: SBS News / Kerrin Thomas

Flinders Island Elder Aunty Lillian Wheatley was also in attendance. She is among a group of eight adults and eight children who occupied the homestead in the 1990s.

“My dream before I leave is to see my people come together on this country and respect it for what it is,” Wheatley says.

Share our old people’s story, it’s about them and what happened here needs to be told.

“Now it’s about truth understanding and it’s about truth acceptance and our people will always fight for a treaty.”