Share and Follow

Would a love letter mean the same if you knew it was written by a robot?

What about a law?

Republicans are asking similar questions in their investigations into former President Joe Biden’s use of the autopen — an automatic signature machine that the former president used to sign a number of clemency orders near the end of his term.

Trump and his allies claim that Biden’s use of the autopen may have been unlawful and indicative of the former president’s cognitive decline. If Biden had to offload the work of signing the orders to a machine, then how can we know he actually approved of what was signed? And if Biden wasn’t approving these orders, then who was?

It is unclear what the outcomes of these investigations will be. More importantly, however, these probes get at a larger concern around how different kinds of communication can lose their meanings when robots or AI enter the mix.

Presidents have used the autopen for various purposes (including signing bills into law) for decades. In fact, the prevalence of the autopen highlights how, today, a presidential signature represents more than just ink on paper — it symbolizes a long process of deliberation and approval that often travels through various different aides and assistants.

The Justice Department under George W. Bush said as much in a 2005 memo advising that others can affix the president’s signature to a bill via autopen, so long as the president approves it.

Trump himself has admitted to using the autopen, albeit only for what he called “very unimportant papers.” House Oversight Chairman James Comer (R-Ky.) even used digital signatures to sign subpoena notices related to the investigation for his committee.

President Obama used the autopen in 2011 to extend the Patriot Act. Even Thomas Jefferson used an early version of the autopen to replicate his handwriting when writing multiple letters or signing multiple documents.

But the dispute around the use of the autopen is more than just partisan bickering; it is an opportunity to consider how we want to incorporate other automating systems like artificial intelligence into our democratic processes.

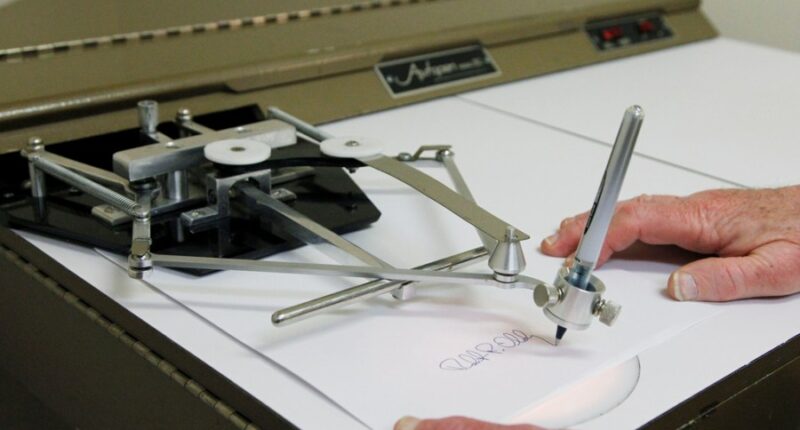

As a researcher who studies the impacts of AI on social interaction, my work shows how automating legal, political, and interpersonal communications can cause controversy, whether via a low-tech robotic arm holding a pen, or through complex generative-AI models.

In our study, we find that autopen controversies illustrate that although automation can make things more efficient, it can also circumvent the very processes that give certain things — like signatures — their meaning.

Generative AI systems are posed to do the same as we increasingly use them to automate our communication tasks, both within and beyond government. For instance, when an office at Vanderbilt University revealed that it had used ChatGPT to help pen a condolence letter to students following a mass shooting at Michigan State University, students were appalled. After all, the whole point of the condolence letter was to show care and compassion towards students. If it was written by a robot, then it was clear the university didn’t actually care — its words were rendered empty.

Using GenAI to automate communication can therefore threaten our trust in one another, and in our institutions: In interpersonal communications, one study suggests that when we suspect others are covertly using AI to communicate with us, we perceive them more negatively. That is, when the use of automation comes to light, we trust and like each other less. The stakes of this kind of breach are especially high when it comes to automating political processes, where trust is paramount.

The Biden fiasco has led some, like Rep. Addison McDowell (R-N.C.), to call for a ban on the use of the autopen in signing bills, executive orders, pardons and commutations. Although Rep. McDowell’s bill might prevent future presidents from experiencing the kind of entanglement the Biden administration has gotten caught up in, it doesn’t address how other kinds of emerging technologies might cause similar problems.

As attractive automating technologies like generative AI become more and more popular, public figures should understand the risks involved in their use. These systems may promise to make governing more efficient, but they still come at a significant cost.

Pegah Moradi is a Ph.D. candidate in Cornell University’s Department of Information Science.