Share and Follow

The paper is stained red for the blood of thousands that were massacred during the Yugoslav Wars.

Painted barbed wire, gravestones and monuments over the map of Bosnia and Herzegovina are a poignant reminder of the atrocities that occurred there. The artwork was gifted to Graham Blewitt as he concluded his decade-long tenure as deputy prosecutor of the ICTY. Source: SBS News / Alexandra Jones

The work is a glimpse into Blewitt’s decade-long tenure as the deputy prosecutor for the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY).

“It’s something I’m very proud of being involved in,” Blewitt says.

During the Bosnian War, the country’s capital Sarajevo was under siege for nearly four years. An estimated 14,000 people including more than five thousand civilians were killed. Source: SBS News / Alexandra Jones

But becoming a pioneer wasn’t something the 78-year-old set out to do.

After a career spent seeking justice for victims and more than a decade investigating war crimes, Blewitt now finds himself watching others struggle to enforce international criminal law in his footsteps.

What’s happening today throughout the world is a complete disappointment.

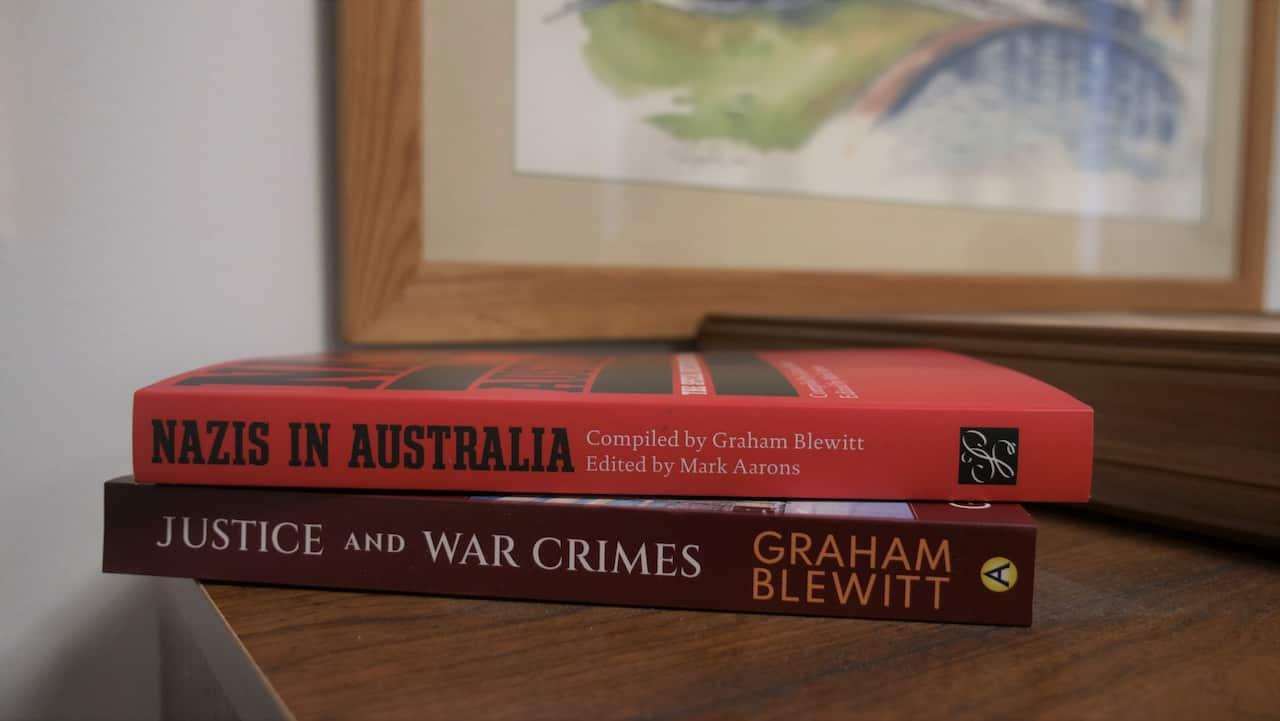

Graham Blewitt’s experiences in war crimes investigations and prosecutions are documented in two published books. Source: SBS News / Alexandra Jones

Nazis in Australia

This included gathering testimonies from persons in Canada, the United States, Israel and Europe.

We undertook investigations by going to those areas, interviewing survivors, interviewing witnesses who were still there and those who had become refugees after the war.

Polyukhovich was accused of helping massacre more than 850 Jews in the northern Ukrainian village of Serniki.

“But we did, and the forensic evidence was overwhelming. It corroborated the evidence of the witnesses that we had found.”

The SIU exhumation team counting bodies at the Serniki mass grave in Ukraine, in June/July 1990. The team recovered German-manufactured bullet cases, date-stamped 1941. The SIU’s photographs and artefacts from the mass graves were donated to the Sydney Jewish Museum. Source: Supplied

Although none of the prosecutions resulted in convictions, Blewitt says the forensic evidence was not challenged.

“It was an important piece of work for Australian legal history and it also gave me the confidence and the experience that I could apply when I got to The Hague later on,” he says.

Graham Blewitt visited the Serniki mass grave site in December 1992, three years after the exhumations. The area has been fenced off and a headstone laid to memorialise the victims. Source: Supplied / Graham Blewitt

Setting up the war crimes tribunal

Its first prosecutor, Richard Goldstone, was appointed in August after being released from the constitutional court in South Africa by Nelson Mandela.

A sketch now hanging in Graham Blewitt’s home office captures the intensity of his early days at the ICTY, establishing the prosecutor’s office, recruiting staff, and launching investigations. Source: SBS News / Alexandra Jones

Prosecuting a genocide

Blewitt says his team “established very early in the piece” that the attack on Srebrenica was carried out by Bosnian Serb forces under the military command of General Ratko Mladić, and leadership of Radovan Karadžić. They set out to indict both.

General Ratko Mladic (left) with Republika Srpska leader Radovan Karadzic (right) in Pale, Bosnia and Herzegovina on 5 August 1993, two years before the attack on Srebrenica that would later be determined to be a genocide. Source: AAP / Stringer/EPA

The investigation soon revealed the existence of mass graves, containing the bodies of thousands of victims who had been executed.

“Once the Serbs found out we were aware of the grave sites, they started to remove the bodies and took them to more remote locations to bury them in secondary graves. We were able to identify both the primary grave sites and the secondary sites, and we decided to carry out exhumations of the bodies in those grave sites.”

“They were able to link the secondary sites with the primary sites, and all that forensic evidence became very important in the subsequent prosecutions that took place.”

ICTY investigators clearing soil and debris from a mass grave containing the bodies of Srebrenica victims near the village of Pilica, on 18 September 1996. Source: AAP / AP

In November 1995, indictments were issued against Karadžić and Mladić, preventing them from attending peace talks in Dayton, Ohio.

“But our view was that you can’t have peace without justice and that they were the primary persons responsible for the genocide, so they had to be prosecuted,” Blewitt says.

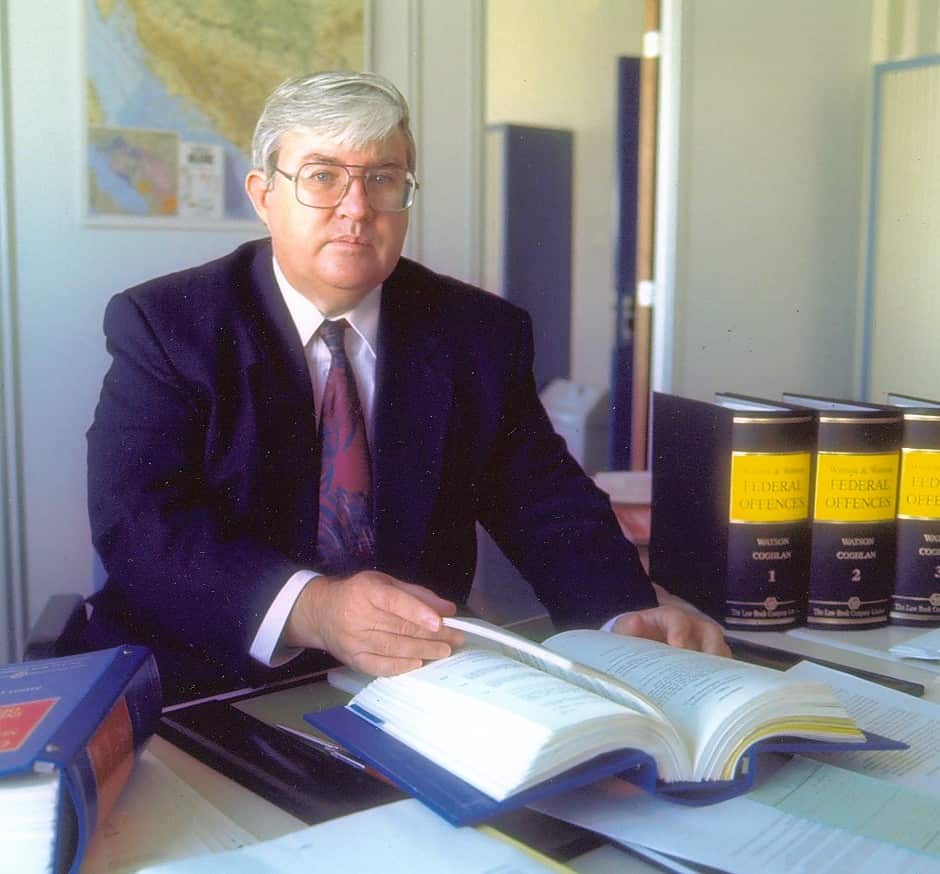

Graham Blewitt setting up the ICTY’s prosecutor’s office in The Hague in 1994. Many of the staff he recruited were Australians who had worked with him on the SIU’s Nazi cases. Source: Supplied

How to arrest an alleged war criminal

“Once the first arrest attempt took place, it opened up the floodgates.”

Before we knew it, the detention centre in The Hague was full and it was necessary to build two additional courtrooms to accommodate all the accused.

“[It] gave confidence to those setting up the permanent international court — the ICC — and when that was established, then clearly the legacy of the tribunal had made itself clear.”

Graham Blewitt (front right) and Richard Goldstone (front left) with the ICTY’s 11 judges at The Hague in 1994. Source: Supplied

Alleged war criminal drinks poison in courtroom

A post-mortem determined he died of a heart attack.

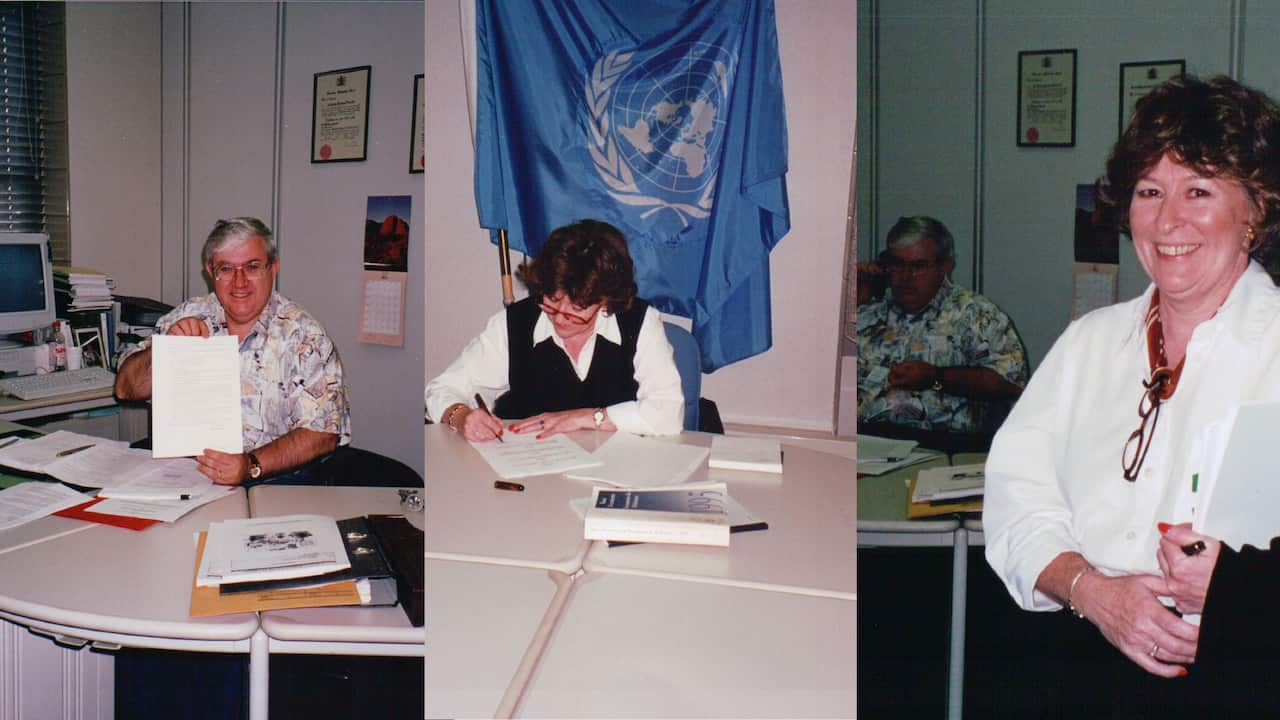

The indictment of Slobodan Milošević, the then Serbian president, in 1999. (Left to right) Graham Blewitt holding up the indictment, chief prosecutor Louise Arbour signing the indictment, and the pair preparing to hand the indictment to ICTY Judge David Hunt, from Australia. Source: Supplied

In 2017, Bosnian-Croat general Slobodan Praljak died after drinking poison in the courtroom.

“But at this point in time, I don’t hold that optimism anymore,” he says.

Frustration as world leaders undermine prosecutions

It noted the ICC — which relies on the cooperation of its 125 member states to carry out any arrest warrants — had no jurisdiction over either Israel or the US, as neither are parties to the Rome Statute, the treaty which created the court.

The ICC has condemned Trump’s executive order, which it said sought to “harm its independent and impartial judicial work”.

Alongside its investigation into Israel, the ICC has also been investigating war crimes and crimes against humanity alleged to have been carried out during the US invasion and occupation of Afghanistan between 2001 and 2021.

The ICC is currently handling 33 cases, has issued 61 arrest warrants, detained 22 people and issued 11 convictions. Source: AP / Omar Havana

Israel accused of war crimes

Netanyahu has repeatedly called the allegations against him “absurd and false”.

He claims a former colleague involved in the Netanyahu and Gallant indictments had resigned from the ICC due to stress after being advised by police to take security precautions, such as getting a bulletproof front door and windows installed at their home.

It’s one thing not to recognise the tribunal, the ICC, but it’s another thing to deliberately interfere with the processes.

The Israeli Prime Minister’s office has previously called the allegations about Mossad “false and unfounded”.

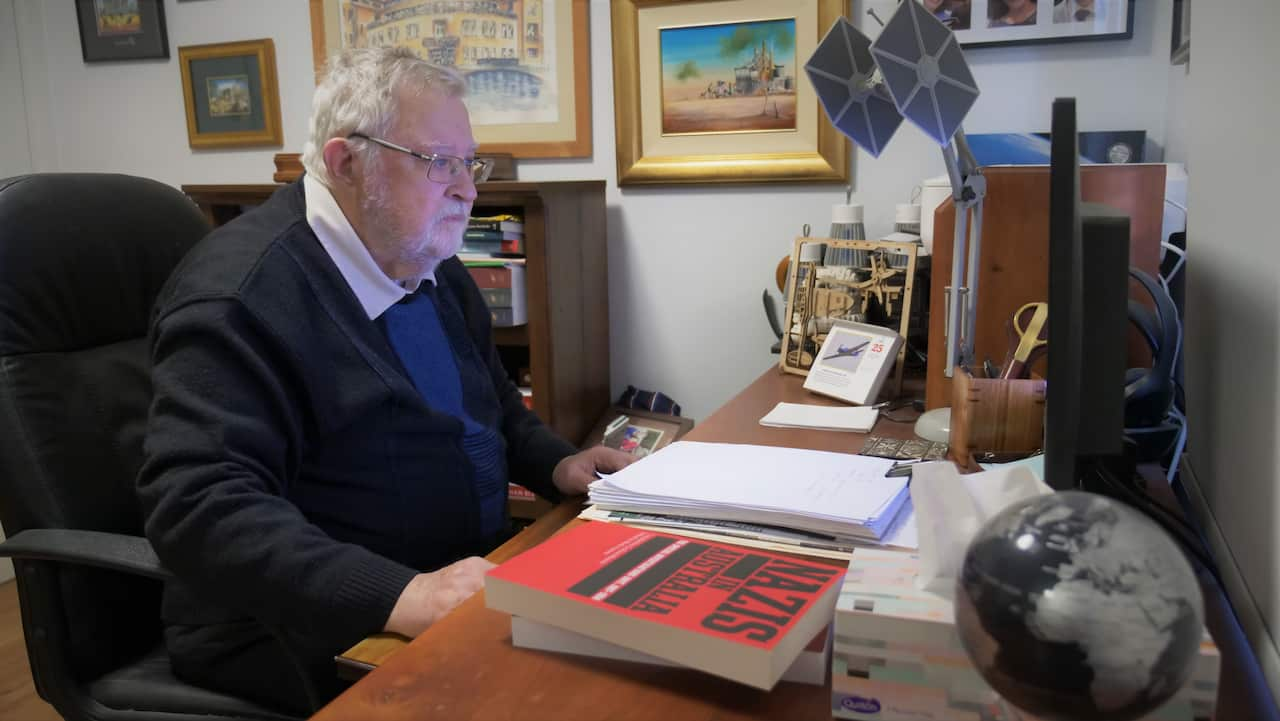

Graham Blewitt was instrumental in setting up the ICTY, which became the blueprint for the International Criminal Court. He has closely followed how its legacy is influencing the ICC’s approach to war crimes allegations in conflicts like Ukraine and Gaza. Source: SBS News / Alexandra Jones

Claims of genocide

Asked why he has this assessment, Blewitt says: “There’s no direct evidence apart from comments made by various Israeli leaders from time to time suggesting that they just want to wipe the Palestinians from the face of the Earth.”

“It is baseless. There is no intent, key for the charge of genocide,” Mencer said.

Israel has repeatedly denied targeting civilians and has accused Hamas of using civilians as “human shields”. Source: AP / Mohammad Abu Samra

How alleged Gaza war crimes could be investigated

Blewitt says the process of investigating alleged war crimes in Gaza would be very different from his experience in the 1990s, when there was no social media or iPhones.

Now anyone with a phone can record what’s happening and there’s no end of evidence for those investigating what’s happening in Gaza.

He explains the ICC can only bring indictments against Israel’s leaders if it can establish that Israel hasn’t fully investigated the alleged crimes and held those responsible to account.

No peace without justice

“If the ICC can outlast the Trump administration and can regain some credibility, then maybe it’ll be back on track,” he says.

Graham Blewitt in The Hague outside the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia at the end of his tenure as deputy prosecutor in 2004. Source: Supplied / Vincent Mentzel 2004

In recent weeks, international condemnation over Israel’s actions in Gaza has grown, particularly in relation to humanitarian aid and the growing hunger crisis.