A Sydney woman who wanted to donate her eggs altruistically to those struggling to conceive at a major IVF clinic, says she was shocked to find couples could exclude donors based on their sexuality.

Alana (not her real name) agreed to donate her eggs through a program at one of Australia’s largest fertility clinics, IVF Australia, which connects hopeful couples with donated eggs and sperm.

As part of this process, Alana, who is bisexual and child-free by choice, was given access to the online profiles of couples seeking donated eggs.

The 35-year-old says she felt uneasy reading the details of people’s lives, including what they did for work, their close family relationships and notes about their fertility challenges.

She was also deeply distressed to read some couples only wanted eggs from heterosexual donors.

Alana says she was shocked there was even a question asking if there was a preference for the sexuality of the donor.

I was even more shocked to see how many people — despite their long heartfelt stories about their fertility journeys — saying that they would only prefer heterosexual donors.

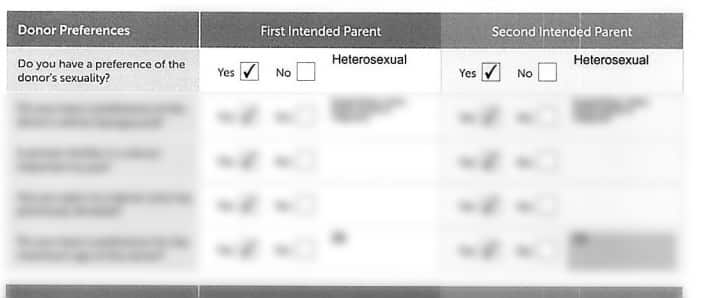

SBS News has been provided with copies of questionnaires completed by potential recipients as part of their profiles. One of the questions asked by IVF Australia in the document is whether the recipients “have a preference of the donor’s sexuality”. Some responses indicate a preference for a “heterosexual” donor.

Alana was also asked to specify her sexuality in a questionnaire she completed.

A questionnaire filled out by parents going through treatment at IVF Australia, who are seeking a donor egg, states a preference for a “heterosexual” donor. Source: Supplied

Alana says she wasn’t warned through counselling sessions with IVF Australia that her sexuality could play a part in the selection process for couples.

I found that quite confronting as a queer person to see how many people were like ‘we don’t want your gay eggs’.

‘Her eggs are as good as any other woman’s’

Stephen Page, a fertility law expert and a board member of the Fertility Society of Australia and New Zealand, says he is shocked to hear about Alana’s experience and believes it’s not lawful under anti-discrimination legislation.

Page says he does not understand why sexuality was included as a specification for potential recipients.

“Let’s put it clearly: surely her eggs are as good as any other woman’s,” he says.

However, a spokesperson for Anti-Discrimination NSW tells SBS News that asking about a recipient’s preference for donor sexuality is unlikely to fall within the discrimination provisions of the act as “the clinic is providing a service to the recipient, and not to the donor”.

In a statement provided to SBS News, Virtus Health, which owns IVF Australia, as well as a number of other IVF and fertility clinics around Australia, says it is “committed to providing inclusive, respectful, and supportive fertility care for all individuals, regardless of their sexual identity, gender, or background”.

“We do not engage in prohibited discrimination on the basis of sexual identity in any aspect of our donor programs,” the statement read.

Virtus Health also says that while some recipient profiles may include personal preferences, “these preferences are self-nominated and not determined or endorsed by Virtus”.

‘Surprise’ over sexual orientation question

Research, including a study led by a University of Queensland researcher and published in the peer-reviewed journal Science in 2019, suggests there is no meaningful way to accurately predict sexual orientation as it can be influenced by a complex mix of factors. This differs from traits such as eye colour, which are based on specific genes being passed down.

Associate professor Alex Polyakov, medical director at Genea Fertility, which owns 19 IVF clinics around Australia, says he is “surprised” sexual orientation is included as a question for donors and recipients.

While matches of donors and recipients that happen outside of clinics are unregulated and may be based on social considerations such as religious beliefs or whether the donor has a tertiary education, Polyakov says donor banks do not tend to include this kind of information.

The National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) guidelines on assisted reproductive technology, which all IVF clinics must comply with, says clinics must allow recipients of donated gametes (egg or sperm) access to donor’s “medical history, family history and any existing genetic test results that are relevant to the future health of the person who would be born”, as well as physical characteristics. The sexual orientation of donors is not mentioned.

Monash IVF, which operates 20 fertility clinics nationwide, told SBS News it actively recruits “donors from all walks of life” and abides by the NHMRC guidelines and “relevant state legislation relating to gamete donations”.

Discrimination against members of the LGBTIQ+ community in Australia’s IVF industry has been widely reported before in the media, with same-sex couples reporting they have been denied access to services.

Ashley Scott, executive officer at advocacy organisation Rainbow Families, told SBS News the IVF industry “is generally speaking quite heteronormative and geared towards straight couples”.

LGBTQ+ people and single people accessing IVF often do face discrimination.

Until recently, same-sex couples faced major hurdles accessing Medicare rebates for IVF treatments due to requirements around medical infertility.

Treated like an ‘egg factory’

Alana says she was first drawn to the idea of donating her eggs after seeing close family and friends struggling with their fertility.

There is a growing demand for donated eggs in Australia; however, few are altruistically donated.

Of the relatively small number of pregnancies achieved using donated eggs in Australia, most consist of women donating eggs to same-sex partners, family and friends.

Alana says she decided to donate her eggs after reflecting on the profound impact it could have on the lives of people struggling to start families.

“I became aware of how few egg donors there are and started thinking more about the fact that I really believe that people who really want to be parents should have that opportunity,” she says.

Alana (not her real name) says she wanted to help couples struggling with fertility. Source: SBS, Getty

While some potential recipients’ profiles excluded her on the basis of her sexuality, Alana notes others wrote heartfelt letters thanking donors in advance and outlining how their children would be loved and cared for.

Despite this, she says she felt some personnel at the clinic lacked empathy for her and treated her as though she were an “egg factory”.

I think egg donation is so rare perhaps that some of the things they have there are just geared towards their usual clients who are going through fertility treatment.

One doctor pressed Alana — who is in a long-term relationship — on why she didn’t want children of her own and said he assumed she must be single.

Alana says she was also told to “not worry about it” when she asked about the statistical likelihood of her eggs resulting in a pregnancy.

While Alana stresses many of the clinicians she interacted with were supportive and professional — some of whom even thanked her for what she was doing — she also feels strongly that the system was not well-designed for her or other altruistic donors.

‘Weird’ request for partner’s consent

Alana was also asked by IVF Australia to get consent for the egg donation from her long-term partner.

While Alana’s partner supported her decision to donate her eggs, the couple felt it was uncomfortable for the clinic to ask for his consent as it encroached on her autonomy.

Following one counselling session, Alana was sent a consent form by the clinic that included her partner’s details.

After expressing her discomfort about this to the clinic, Alana was told that if her partner “wasn’t supportive” they could proceed regardless — but Alana wanted to make it clear that this wasn’t the case.

“It was just that we didn’t want to go down that route of asking him for permission,” she says.

“[He] didn’t want to, [he] didn’t feel he had the right to give permission for my gametes to be donated either, so we both felt weird about it.”

Under Victorian, NSW and Queensland law, spouses are not required to give consent for their partners to donate gametes.

The NMHRC guidelines for gamete donation say clinics “should encourage the potential donor to include their spouse or partner in the discussions about their gamete donation” and in counselling sessions.

However, some clinics insist it is a requirement and many online resources in these states say it is legally required.

Page says this confusion is an example of the ways that the legislation for IVF in Australia is a “mess”.

“The [Fertility Society of Australia and New Zealand] has called for a national law or uniform laws so that we don’t have eight systems for 27 million people,” he says.

‘Not enough focus on the egg donor journey’

Alana says while the physician who ended up performing her egg retrieval was extremely warm and professional, the process of altruistic donation as a whole was fraught and emotionally taxing.

I would love to just recommend to anyone thinking about donating eggs [to] go ahead, but I don’t think I can do that without reservation and without disclaimers because you honestly don’t really know until you get in there what you’re going to get.

Page says IVF clinics should be doing what they can to encourage altruistic donors, considering the scarcity of eggs and the high demand for them in Australia.

“Prospective parents should not have to go overseas to access eggs, as some do,” he says.

“I would encourage all clinics to make their processes as warm and welcoming as possible with donation, not only for prospective donors but also for prospective recipients.”

Alana says she has no plans to donate eggs again.

“I don’t think I would do it again. I have thought about it — regardless of whether this leads to a pregnancy or multiple pregnancies for the recipient, I think I am ‘one and done’,” Alana says.

While helping a couple struggling with their fertility was always front of mind for her, Alana says at times she felt she wasn’t treated “as a human being with my own complex thoughts and feelings and experiences”.

“I do think there’s not enough focus on the egg donor journey and experiences because I guess you’re just a means to an end for someone else who is their main client.”