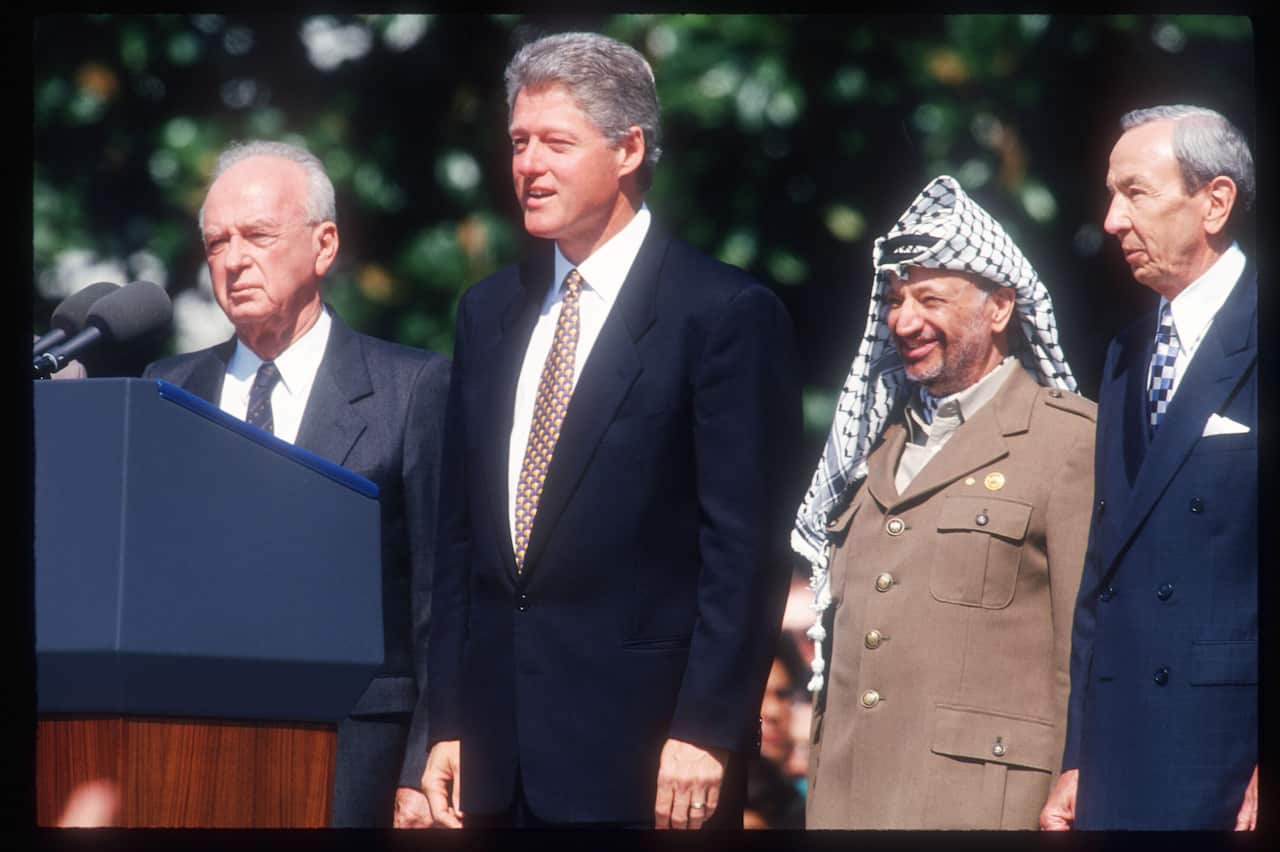

When the first of the Oslo Accords were signed on the White House lawn more than 30 years ago, there was hope within the international community that the Israeli-Palestinian agreement would establish a foundation of peace in a land marked by “warfare and hatred”.

Then-United States president Bill Clinton described it as a “brave gamble”, contending the future could be better than the past. It was signed by then-Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin and then-Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) chair Yasser Arafat.

As part of the agreement, the PLO recognised Israel and its citizens’ right to live in peace, and in turn, Israel recognised the PLO as the representative of the Palestinian people.

It also led to the creation of the Palestinian Authority (PA), which was to act as an interim government in the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

(Left to right) Then-Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin, then-US president Bill Clinton, then-Palestine Liberation Organization chair Yasser Arafat and former US secretary of state Warren Christopher pose during the signing of the Oslo peace accord in 1993. Source: Getty / Dirck Halstead

But the promise of the PA to establish Palestinian self-governance stalled after Rabin was assassinated in 1995 by a Jewish extremist. Twenty years later, the latest bloody conflict — on October 7 2023 — has led to an escalation of the ongoing war in Gaza.

Much rests now on the PA, as Arab and Western countries move towards recognising a Palestinian state, and its future role in governing Gaza once the war ends.

But how would politics under the PA work?

Who represents the Palestinian people?

This week, Australia announced its intention to recognise a Palestinian state at the United Nations General Assembly in September, following similar announcements from France, Canada and the United Kingdom.

A joint statement released by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and Foreign Minister Penny Wong says Australia’s recognition will contribute to international momentum towards a two-state solution, a ceasefire in Gaza and the release of hostages.

“The international community is moving to establish a Palestinian state consistent with a two-state solution,” the joint statement reads.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has announced Australia will recognise Palestinian statehood in September. Source: AAP / Dean Lewins

In response, the Opposition spokesperson for foreign affairs, Michaelia Cash, raised the question of whether it was even possible for Australia to recognise Palestinian statehood.

“He’s [Albanese’s] now committed Australia to recognising as a state — an entity with no agreed borders, no single government in effective control of its territory and no demonstrated capacity to live in peace with its neighbours,” she told ABC’s Radio National Breakfast program.

International law expert at the Australian National University, Professor Donald Rothwell, believes the Palestinian territories do satisfy the Montevideo Convention criteria for statehood: that it has a permanent population; a defined territory; government; and capacity to enter into relations with other states.

While the boundaries of a Palestinian state are contested by some, Rothwell says this is not exceptional, pointing to the recent boundary dispute between Cambodia and Thailand, and so wouldn’t preclude formal statehood.

The PA could also be seen as a legitimate government, even though there are doubts about its effectiveness, Rothwell says.

Even if the legal criteria are met, he says the decision on whether a Palestinian state could be ratified is subject to a “diplomatic and political equation”.

For example, Taiwan also meets all the criteria of the Montevideo Convention, but its statehood is not recognised by the vast majority of the international community, including Australia, for political and diplomatic reasons.

Perceptions of the Palestinian Authority

Australia is just one of the countries that appears to be relying on the PA being an authoritative representative of the Palestinian people.

In his statement flagging Australia’s recognition of Palestinian statehood, Albanese said the country’s position is “predicated on the commitments we have received from the Palestinian Authority”.

“The world is seizing the opportunity of major new commitments from the Palestinian Authority, including to reform governance, terminate prisoner payments, institute schooling reform, demilitarise and hold general elections,” he said.

He said the PA had also restated its recognition of Israel’s right to exist.

“The president of the Palestinian Authority has reaffirmed these commitments directly to the Australian government,” Albanese said.

The statement appears to acknowledge concerns around the PA and how it has operated in the past.

In July, the US state department announced it would introduce sanctions against officials of the PA and members of the PLO, for continuing to support terrorism, including the incitement and glorification of violence (especially in textbooks), and providing payments and benefits in support of terrorism to Palestinian terrorists and their families.

Professor Greg Barton, chair of global Islamic politics at Deakin University, says the PA is widely seen as corrupt and incompetent.

For 20 years, it has been led by Mahmoud Abbas, who will turn 90 in November. Abbas was originally elected for a four-year term, but his rule was extended indefinitely after a vote by the PLO Central Council in 2009.

It’s remained an old school kind of family concern with power centred around some individuals, who are now very aged.

“That’s not to say the PA hasn’t done any good, but the perception among the Palestinian people is that it’s been slow to share the resources that have been given to it,” Barton says.

Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas will be turning 90 later this year. Source: AAP / Alaa Badarneh/EPA

In an interview with SBS News this week, PA foreign minister Varsen Aghabekian Shahin, said the authority is committed to reform and conducting elections.

She said Abbas also wants a demilitarised Palestinian state in the future, but these guarantees could only be delivered if there is a ceasefire in Gaza.

Once the Palestinian Authority is enabled to govern in Gaza — when that situation materialises on the ground — the people will see a different kind of future, rather than today’s reality, which is plagued by killing, destruction [and] starvation.

Palestinian Authority has been ‘undermined’

Barton says while the PA has acted as its own enemy in many ways, it has also been undermined by Israel.

“It’s partly their fault … and partly because of the conditions that Israel has put in place so that it’s difficult for them to ever be in a situation where they’re going to get popular,” he says.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who does not support a two-state solution, said in a speech in February last year: “Everyone knows that it was me who — for decades — has blocked the establishment of a Palestinian state that would endanger our existence.”

Netanyahu was also an outspoken critic of the Oslo Accords when he first came to power in 1996, a year after Rabin was assassinated. He is now in his third term as prime minister.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was an outspoken critic of the Oslo Accords when he first came to power in 1996. Source: AAP / Abir Sultan/AP

Netanyahu’s latest move to take control of Gaza City has also raised concerns internationally, despite his claim that the move would implement a “transitional authority” and “civilian administration” in Gaza, seeking to live in peace with Israel.

Shahin said if Israel continues to undermine Abbas, his government and the Palestinian leadership, then Palestinians will continue to lose faith in the PA.

“If [they] continue to be undermined through demographic changes by Israel, geographic changes by Israel, through exploitation of our resources, through violation of our rights, then the people would continue to lose trust in a leadership that promised them peace,” she said.

“We need to see movement on the ground that shows people that there is a light at the end of the tunnel.”

Barton says settlement expansion in the West Bank, both legal and illegal, is one example of how the Israeli government has sabotaged the PA.

“It’s just made it very hard for the Palestinian Authority to exercise any real control and to build popular support,” he says.

No influence in Gaza

The PA currently has no authority in Gaza and its administrative centre is based in Ramallah City in the West Bank.

Israel pulled out of occupying Gaza in 2005 — the same year Abbas won the presidential election, but the militant political group Hamas won legislative elections in 2006.

Fatah, the party that leads the PA, fought a war with Hamas between 2006 and 2007, after failing to reach a power-sharing deal and agreement over control of border crossings.

It led to Hamas taking over the Gaza Strip in 2007, which Barton says has meant Fatah leaders and other members of the PA face a degree of persecution in the area.

A map showing Gaza, Israel and the West Bank. Credit: SBS News

According to the global Islamic politics expert, Hamas had been running Gaza similar to a mafia state before October 7.

“They were controlling the economy, intimidating anyone who threatened them, carrying out summary punishment — public executions of people who oppose them — terrifying the population [and] getting people to inform on their neighbours,” Barton says.

When asked whether Hamas, which is also opposed to a two-state solution, still holds influence over the Palestinian people, Shahin said most of its senior leaders had been targeted and assassinated by Israel, and the rest are most likely outside Gaza.

“When people see a change, when people see a move towards peace, when people see a move towards a better life, I think the whole situation will change,” she said.

There has been widespread destruction in Gaza since a terrorist attack on October 7, 2023 saw Israel engage in an ongoing war with Hamas. Source: Getty / Salah Malkawi

Shahin said the PA has no direct contact with Hamas’ senior leaders that she knows of.

“But I think there are numerous contacts between other intermediaries. Egypt speaks with Hamas, Qatar speaks with Hamas, Türkiye speaks with Hamas, so we have discussions through other entities,” she said.

Former Australian ambassador to Israel, Dave Sharma, who is now a Liberal senator for NSW, tells SBS News he also doesn’t think Hamas has any official communication channels with Israel.

“To the extent, [that] diplomatic channels exist, it’s through intermediaries like the Egyptians or the Qataris,” he says.

The importance of other nations

Barton says there’s a chance the PA can emerge as an authoritative representative of the Palestinian people, but it isn’t going to happen “organically” and help is needed.

He says the PA could be remade “to bring in new leaders and to build capacity, and bring in accountability mechanisms and turn it into something that’s viable”.

The smartest thing for Abbas to do would be to support a leadership transition rather than oppose it, he says.

Barton points to the reconstruction of the Gaza Strip and the massive scale of work that will be required in the aftermath of the war.

“It would be with Saudi Arabia, and perhaps with the UAE, and with the support of Jordan and Egypt and with Qatar and possibly Türkiye,” he says.

That would also require support from Europeans and others, including potentially Australia.

Shahin acknowledges the long road ahead to rebuild Gaza.

“What is needed in Gaza in ‘the day after’ is just mind-boggling,” she said.

“We cannot even begin to imagine the enormity of the need, given the destruction and the devastation, so the more support, the better.

“That support will be very much needed in terms of financial support, and in terms of technical support, and in terms of political support in the international arena.”

Who’s going to defend Palestinian state?

If a Palestinian state does emerge that is not occupied by the Israel Defence Forces, Rothwell points out, it will also be defenceless.

“There’s going to be a need for some discussion among this sort of growing group of Western like-minded countries — probably in conjunction with the Arab League — of inserting some sort of security stabilisation force, not only to provide internal security within Palestine, but also to protect Palestine from attacks from its neighbours,” he says.

Once Palestinian statehood is recognised in September, Rothwell says Australia could enter into legally binding treaties, engage in trade and directly fund aid without going through the UN or other agencies.

Perhaps most importantly, Australia can directly contribute to the rebuilding of Gaza, which is going to be an important project at the end of the conflict.

Rothwell notes Albanese’s statement also hinted at defence force personnel being deployed.

“We will work with partners on a credible peace plan that establishes governance and security arrangements for Palestine and ensures the security of Israel,” it reads.

A turning point

Barton says the good intentions of the Oslo process have so far been stymied, but it’s possible the world is at an inflection point.

“The international community is now at a point where it says we can’t allow the Israeli government just to do whatever it wants [even if it’s in response to October 7],” he says.

“Rebuilding the Gaza Strip is a pressing need.”

He also points to a statement from the Arab League — including Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Egypt — that calls for Hamas to disarm and relinquish power in the Gaza Strip.

This is the first time we’ve seen such concerted agreement to speak critically of Hamas and recognise that Hamas has no future role to play in Palestine.

“That’s the first time we’ve come to this point.”

Barton says the UN assembly meeting next month will be critical.

“Despite the failure for decades [to] bring about change, now might be the beginning in which things begin to change.”

While the conflict might seem intractable, Barton says there are historical examples of former enemy states, such as Egypt and Jordan, now working together.

“It’s not as hopeless as it might sound.

“There are challenges but they’re not insurmountable.”