This article contains references to rape, sexual assault and child abuse.

Dateline’s latest episode, Surviving My Father, on 26 August live at 9.30pm on SBS or SBS On Demand.

At a park in the modern metropolis of Shenzhen in southern China, a father meets his daughter. It looks like an ordinary encounter but the daughter, Li, has been preparing for this moment for years.

“I was all in black seeing him that day as if attending his funeral,” she said.

“My heart was beating fast …”

Across the footpath, hiding in the shrubs, her fiancé secretly films the encounter while Li wears a microphone to capture the confrontation.

“Pain is all I can remember about my first sexual experience,” Li tells her father, Tang, in her attempt to bring her father to justice for child sexual abuse.

“It only lasted one or two seconds.”

Over the course of the conversation, Tang admits to raping and repeatedly sexually harassing his daughter between 2009 to 2013.

It’s strong evidence for Li’s lawyer, Wan. She encourages Li to call the police and make a report, so that the evidence can be used in later criminal proceedings.

In 2009, when the abuse started, Li was 15 years old.

‘It took root in my heart’

Looking back, Li said she wasn’t aware that what she experienced during her teenage years was sexual assault.

Li’s mother, Lui, didn’t approach the authorities when she was told of the abuse, and said her reluctance to help her daughter remains a source of regret for them both.

“What I regret the most is not calling the police in 2009 because I felt embarrassed to even mention it,” Lui said.

“I feel miserable. I’d rather go to jail myself than have her cry.”

Almost a decade later, it continues to put a strain on their relationship.

“It has haunted me for many years … It took root in my heart and I hope we can cut it open,” Li said.

“I must dig out the root.”

Prolonged impact of trauma

Li’s fiancé, Ma Ke, said delays in disclosing and reporting the abuse has meant Li continues to experience ongoing trauma.

“When our relationship turned romantic, she suddenly brought it up with me. She simply asked me if I could not accept her past … we could break up.

“I was shocked at first. My heart aches knowing what happened to her.”

He said Li still has nightmares and can wake up screaming during the night.

Ma Ke has supported Li in her journey to justice. He believes it’s important she has someone behind her, “encouraging her and guiding her through it”. Credit: Supplied

“She doubted whether it made sense to do this or whether she was right or wrong.

“Even worse, she thought it was her fault.”

While Li said she has “moved on” from the experience, she was forced to confront her past and relive “painful memories” as part of the process of finding evidence to help prove her allegations.

“I want to try my best and consider everything that I might overlook, leaving no possibility of escape for the perpetrator [Tang].”

Reporting China’s sexual violence rates

The prevalence of sexual abuse in China has been projected to increase, according to Iranian academics who modelled data from the Global Burden of Disease archives.

Researchers found other countries with upward trends included North Korea and Taiwan – while sexual violence in most of the world continues to decline.

Most cases of child sexual abuse are not publicly disclosed or reported in China and no national statistics are published. This means it can be hard for NGOs and the media to establish accurate figures, according to a 2024 report by The University of Auckland and The University of New South Wales.

The report also found there were a number of factors contributing to victims and survivors of child sexual abuse in China not disclosing their experience. This ranged from individual barriers, like a lack of awareness about abuse, to cultural barriers like internalised shame or fear of damaging their reputations.

But after China’s #MeToo movement, a series of sexual harassment allegations did make headlines.

In 2018, a female intern took a high-profile news anchor to court for sexual abuse. It inspired a wave of women to share similar experiences online, but the court ultimately dismissed her appeal due to “insufficient evidence”.

The woman at the centre of the case, Zhou Xioxuan told media at the time, “I’m disappointed but it’s also somewhat expected”.

In July 2024, a PhD student posted an hour-long video to the social media platform, Weibo, accusing her supervisor of ongoing physical and verbal harassment. Within a day, the university had fired the professor. In its statement the university cited his “moral misconduct”, not sexual abuse.

Last year, Sophia Huang Xuequin, an independent Chinese journalist who covered gender-based violence was sentenced to five years’ jail for “inciting subversion of state power”.

The court said that a regular gathering she organised with labour activist Wang JiangBing “incited participants’ dissatisfaction with Chinese state power under the pretext of discussing social issues”, according to the Free Huang XueQuin & Wang JianBing group,

Guangzhou People’s Intermediate Court found #MeToo activist Huang Xueqin guilty of subversion. Source: Getty / South China Morning Post

Potential barriers to disclosing child sexual abuse have also been attributed to Chinese cultural values, which emphasise family loyalty, including to elders and attitudes around sexuality in China, according to the study by The University of Auckland and University of New South Wales.

Response from family members

It took Li years to report her father’s abuse, and she said it can be a gruelling and emotional process.

But after Li contacted authorities, she claims she experienced more abuse, this time, in the form of threatening voice messages from her uncle. In one, her uncle threatened:

“Remember your life is a failure just like your mum’s. Shame on you.”

But Li’s lawyer, Wan, reassured her:

“They equate prosecuting your father with harming the interest of the family. It’s not that you hurt the family, it’s your father. He should take responsibility for what he did.”

Li responded with a simple statement over text.

“Stop blaming my mother. Her only fault was marrying your brother in the first place.”

In 2016, China enacted its first domestic violence laws, which include physical and psychological abuse. It also allowed people to apply for protections, including restraining orders.

But Chinese domestic violence legislation and rape laws have continued to face criticism. Currently, marital sexual assault and rape is not explicitly defined as a crime, which may make it difficult to prosecute.

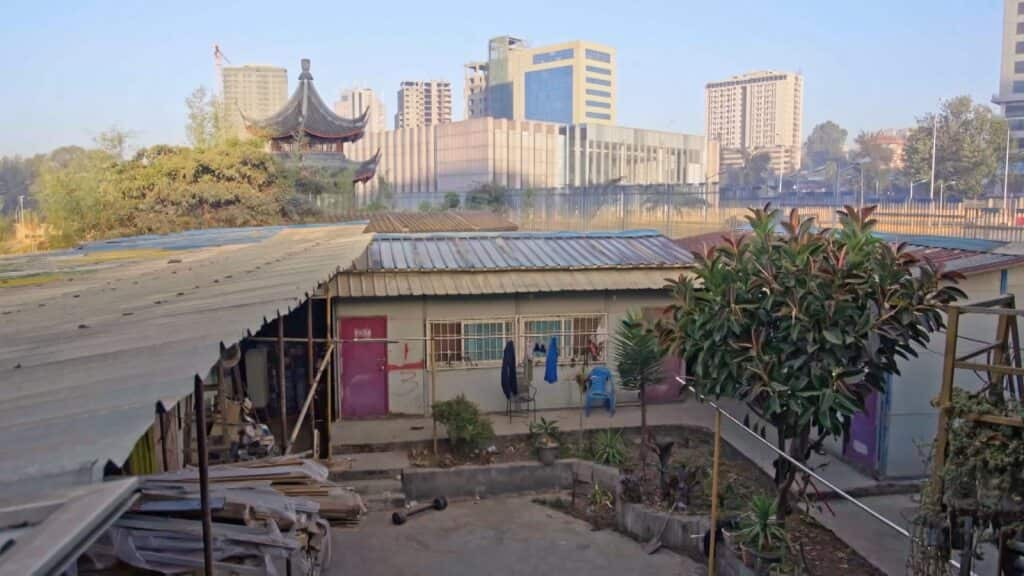

Li has moved overseas with her partner, Ma Ke. She said they have established a new life in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Credit: Supplied

In hopes of distancing herself from her parents and her past, Li relocated to Ethiopia in East Africa.

“Having a house means breaking away from your parents. Working abroad, all the more so.”

‘I’ll never forgive them’

Unable to attend her court hearing in China in person, Li provided evidence via video from Ethiopia. Her mother also agreed to testify in support of her.

Ultimately, Li’s father Tang was found guilty of sexual assault and rape and sentenced to 12 –and-a-half years in prison.

After the trial, Li said she remains unsure if she will keep in contact with her mother.

She recently tied the knot with Ma Ke but did not invite her mother to the wedding.

Now, she is trying to move forward with her life.

“It took me a lot of courage to speak up … about Tang’s brutality,” Li said.

But while Li is satisfied with the trial results, which she said has given her closure, the trauma continues to stay with her.

“I feel much better knowing that the wrongdoer has been punished. I think reporting these things to the police can help victims recover from the trauma.

“I want to live my life well. I won’t live my life with resentment.

“But I’ll never forgive them.”

If you or someone you know is impacted by family and domestic violence or sexual assault call 1800RESPECT on 1800 737 732 or visit 1800RESPECT.org.au. In an emergency, call 000.

Anyone seeking information or support relating to sexual abuse can contact Bravehearts on 1800 272 831 or Blue Knot on 1300 657 380.

The Men’s Referral Service, operated by No to Violence, can be contacted on 1300 766 491.

Readers seeking support can ring Lifeline on 13 11 14 or text 0477 13 11 14 and Kids Helpline on 1800 55 1800 (for young people aged up to 25).