Share and Follow

“We together have a front-row seat to history: We’re returning to the moon after over 50 years,” NASA acting deputy associate administrator Lakiesha Hawkins said at a news conference on Tuesday.

The Artemis 2 crew comprises of astronauts (from right to left) Reid Wiseman, the mission’s commander who last flew on a Russian Soyuz rocket to the International Space Station in 2014; Victor Glover, the pilot who flew to space in 2020 on a SpaceX ISS mission; Christina Koch, a mission specialist who flew on a Soyuz ISS mission in 2019; and Canadian astronaut Jeremy Hansen, another mission specialist who will fly to space for the first time. Source: Getty / Austin DeSisto / NurPhoto

The Artemis 2 mission follows an uncrewed mission that put a spacecraft into lunar orbit in November 2022 and returned it to Earth roughly four weeks later.

According to NASA, the Artemis project’s goals are to “explore the Moon for scientific discovery, economic benefits, and to build the foundation for the first crewed missions to Mars”.

A ‘free ride’ and a ‘slingshot’

“This is done in such a way that they’ll use, in essence, the moon’s gravity to get a free ride back — just in case anything happens,” he said.

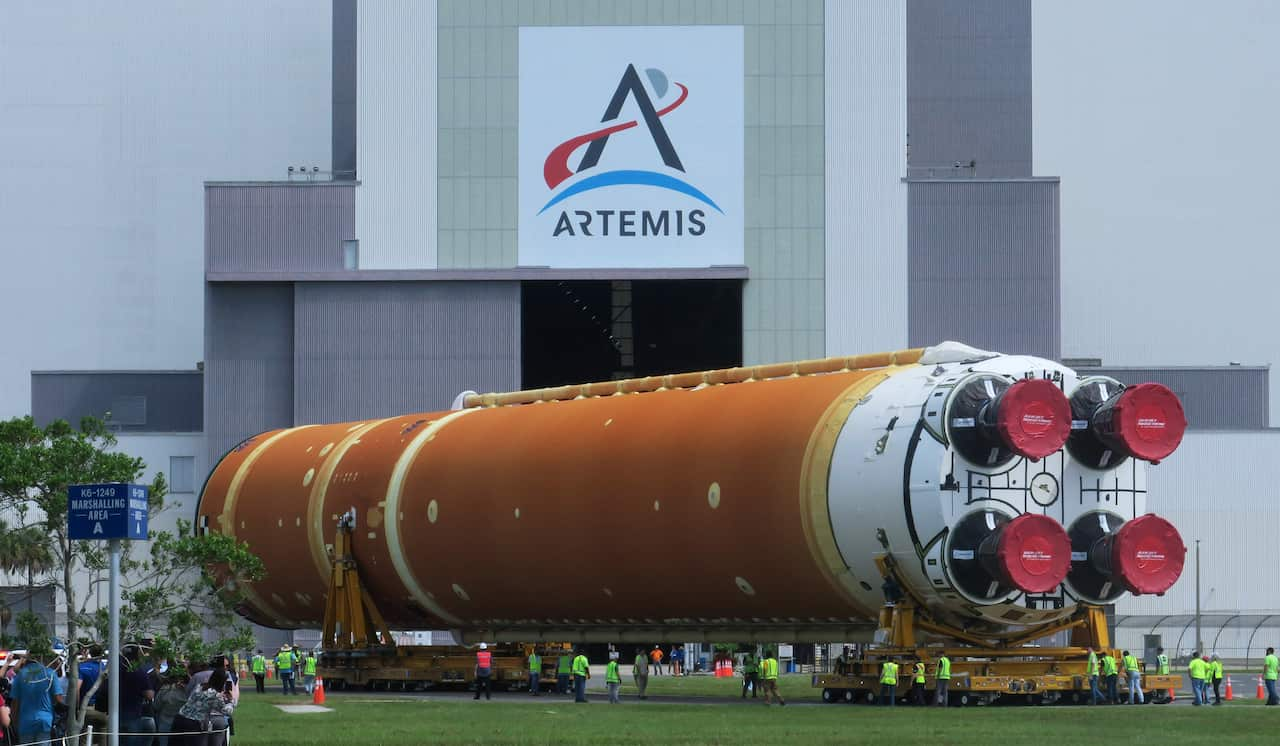

Workers transport the 64m tall SLS core stage for the Artemis II moon rocket at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida in July last year. Source: Getty / Paul Hennessy / Anadolu

“So it’s a full circle around the earth, and then a slingshot around the moon back to the Earth.”

NASA has said, should the mission go according to plan, the Artemis 2 spacecraft will land in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of San Diego.

‘The Apollo program for our era’

“They want to bring people back to the Moon, not just for three years as they did during the Apollo era, but for a more sustainable presence.”

“At the moment, we’ve had a few sample return missions, most recently by the Chinese. But what they bring back is a relatively small volume of material, often no more than one or two kilograms of regolith, which is the lunar soil,” he said.

A 3.2-billion-year-old rock of sintered lunar soil collected by Apollo 15 inside a pressurised nitrogen-filled case. Source: AP / Michael Wyke

“With humans there, you could look at larger volumes, and particularly what’s of interest for scientists is ‘where does the moon come from?’.

According to NASA, “several theories about our moon’s formation vie for dominance” but nearly all agree that the moon “was born out of destruction” — most likely an object or series of objects crashing into the Earth and flinging molten and vaporised debris into space around 4.5 billion years ago.

‘Some very difficult conversations’

“Over the last couple of years, there has been a lot of interest in the southern hemisphere of the moon, particularly south of the moon’s polar circle, where there might be frozen water that could potentially be used for resources for more permanent settlement or even as a reservoir for further journey into the solar system,” he said.

“And so there’s going to be some very difficult conversations and hopefully some really good understanding reached, to ensure that we get the best for everybody with a minimum harm.”

A new space race?

The Trump administration has referred to a “second space race,” a successor to the 20th-century Cold War competition over spaceflight technology between the US and the Soviet Union.

De Grijs, who is also executive director of the International Space Science Institute–Beijing, says that it may be “seen as a space race from the US side”, but that’s not a feeling shared by China.

A Yaogan-45 satellite blasts off from the Wenchang Spacecraft Launch Site in Hainan Province, China, on 9 September. Source: AAP / Yang Guanyu / EPA

“Many people in the West, particularly, say: ‘this is a new space race with China’, and that’s how it’s characterised, but I actually disagree with that assessment,” he told SBS News.