Share and Follow

It’s living history, and a new owner can live in its history, too.

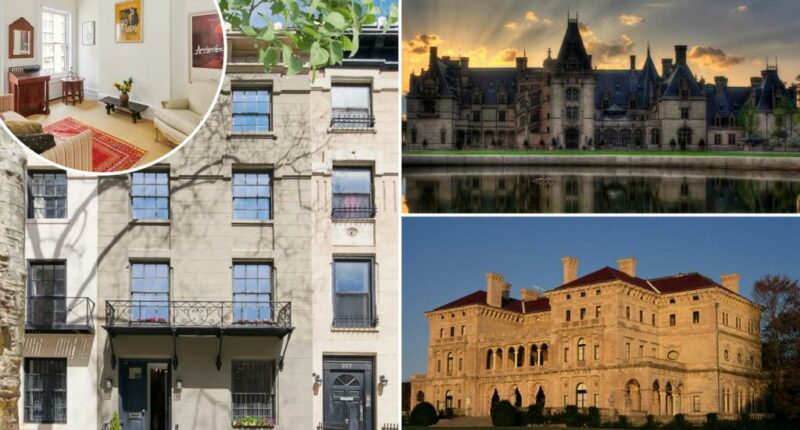

On the market for the first time in approximately 25 years at $5.49 million, the four-story townhouse located at 225 E. 62nd St. is a remarkable surviving piece of Manhattan architecture crafted by Richard Morris Hunt. The Post has discovered that Hunt was the pioneering architect who introduced the Beaux-Arts style to the United States.

Hunt is famed for his work on the Biltmore Estate in North Carolina and the Breakers in Rhode Island. He also designed both the Statue of Liberty’s pedestal and the entrance façade of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Despite his significant contributions to architecture, “from what I understand, this was only one of four small residential townhouses in Manhattan that was designed by him,” Dianne Weston of Sotheby’s International Realty, the property’s listing agent, mentioned to The Post.

“Most of the other buildings were either public or large private homes, like the Vanderbilt mansions.”

Many of those grand mansions, including the Elbridge Gerry residence that once stood where the Pierre Hotel now rises, have long since been lost to the wrecking ball.

“The other thing that he designed, which was unfortunately demolished, was on the location of the Frick Museum called the Lenox Library,” Weston said. “So he really designed for people with the best addresses in town.”

That makes 225 E. 62nd St. a rare survivor, both architecturally and historically. And now, a lucky house hunter can claim it for themselves.

Built in 1873 in Hunt’s signature French Second Empire style, the townhouse sits within the Treadwell Farm Historic District, an enclave of just 75 homes stretching across two tranquil blocks between Second and Third avenues.

With its original stoop, wrought-iron railings and a charming Juliet balcony, the façade retains its 19th-century grandeur.

“It has been really well maintained,” Weston said, adding that the current owner purchased it in 2001 and undertook significant renovations the following year.

Inside, the 2,850-square-foot home is rich with preserved elements

“The three marble fireplace … the balustrades and the spindles going up the staircase … Most of those are original, as you can tell, because they’re not necessarily up to code,” Weston said. “But a lot of the other interior details were lost. When my owner bought it, it was a true wreck. And it was in very sad condition.”

The resulting renovation deftly marries modern comfort with period character.

The second-floor double living room spans the entire depth of the house and features 10-foot ceilings, Douglas fir floors, and sun pouring in through oversized windows. A hand-carved marble mantel anchors the space, while discreet lighting systems cater to collectors who might wish to highlight their art.

The chef’s kitchen on the parlor floor — fitted with solid maple cabinetry, a six-burner commercial range and a mosaic tile backsplash — flows into the dining room and opens out to a rear garden.

Beyond that sits one of the home’s most surprising features: a standalone brick garden studio built in the 1930s, reminiscent of a carriage house and outfitted with skylights, radiant heated floors and its own HVAC system.

“Everyone who comes there really likes that feature a lot,” Weston said. “It affords you additional space for whether it’s a home office as it has been used. It’s a beautiful private space… quite a comfortable little space. It could be an amazing little yoga studio, meditation space, anything like that.”

“There was no original carriage house back there. It would have been larger,” she said, adding that because the studio “is grandfathered in. You could demolish it if you want to create just a yard. But it really is an interesting little addition to the house.”

The home includes four bedrooms, 3.5 bathrooms, a library, a home office and a finished English basement level with its own street entrance, large bedroom, laundry room and full bath.

Weston believes the townhome’s smaller size compared to others, its history and flexibility set it apart from larger, darker townhouses.

“You get fabulous sunlight all day. And that’s rare on some of these townhouse blocks,” she said.

Though the property is steeped in old-world allure, Hunt’s vision was always one of forward movement.

After graduating from the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris — where he was later placed in charge of completing the Louvre after the death of its architect — Hunt returned to the US determined to elevate architecture’s role in shaping national identity. Through civic monuments, society homes, and artistic ideals, he believed America needed culture.

As for the seller, “It’s sort of part of downsizing and relocating his life elsewhere,” Weston said. “They have multiple homes overseas. And so they really don’t need the townhouse anymore, even though it has been a precious home to him.”

Weston is co-listing the property with Michele Llewelyn and Helene Warrick.