Share and Follow

When it comes to dark matter, seeing is no longer believing. An astounding revelation has emerged, captivating astronomers worldwide, as scientists unveil the existence of a colossal dark object in the cosmos, completely invisible to the human eye. This groundbreaking discovery has been detailed in a recent study published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

The mysterious entity, yet to be christened with a name, possesses a staggering mass—about a million times greater than that of our sun—yet it emits no light, according to reports from Phys.org. Intriguingly, this cosmic enigma is situated more than 10 billion light-years away from us, meaning we are viewing it as it existed when Earth was merely 6.5 billion years old, less than half its current age.

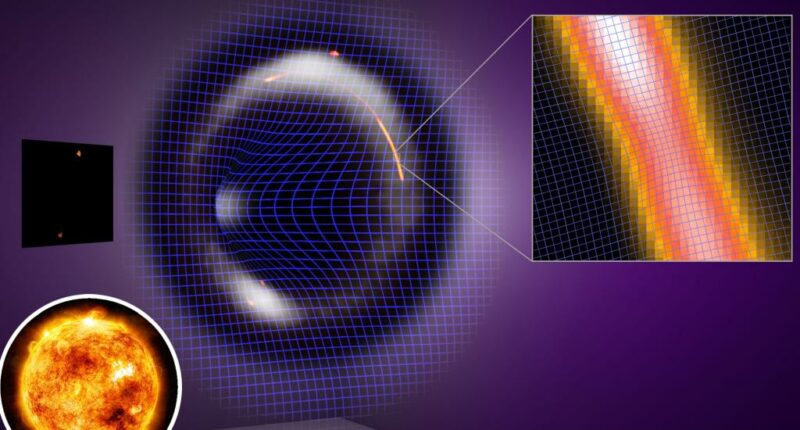

Due to its invisibility, researchers utilized the phenomenon of gravitational lensing to detect the presence of this dark matter. This process involves observing how the light from a more distant object is distorted and bent by the gravitational pull of the dark matter, akin to gazing into a cosmic funhouse mirror.

“Hunting for dark objects that do not seem to emit any light is clearly challenging,” explained Devon Powell, the lead author of the study from the Max Planck Institute of Astrophysics in Garching, Germany. “Since we can’t see them directly, we instead use very distant galaxies as a backlight to look for their gravitational imprints.”

“Hunting for dark objects that do not seem to emit any light is clearly challenging,” said lead author Devon Powell of the Max Planck Institute of Astrophysics in Garching, Germany. “Since we can’t see them directly, we instead use very distant galaxies as a backlight to look for their gravitational imprints.”

Despite dwarfing our solar star, this particular object was the lowest-mass object ever discovered using the gravitational lensing method — by a factor of 100.

To shine a proverbial light on said mysterious object, the team relied on a network of telescopes around the world, including the Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia and the Very Long Baseline Array in Hilo, Hawaii.

They then correlated the resultant data to create an “Earth-sized super telescope,” as the researchers described it, with which they could capture the subtle signs of gravitational lensing and make it less of a cosmic shot in the dark.

They also had to develop advanced computational algorithms and even harnessed supercomputers to crunch the sprawling datasets.

Thankfully, their analysis paid dividends.

“From the first high-resolution image, we immediately observed a narrowing in the gravitational arc, which is the tell-tale sign that we were onto something,” said John McKean, of the University of Groningen of the Netherlands, who spearheaded the data collection. “Only another small clump of mass between us and the distant radio galaxy could cause this.”

Discovering clumps are significant because they expand our understanding of dark matter, material that is believed to exist in space but without visible light to prove it.

In fact, some studies have suggested that dark matter may even predate the Big Bang, the rapid inflation of our universe some 13.8 billion years ago.

“Finding dark matter clumps like this is a critical test of our understanding of how galaxies form,” said Dr. Powell. “The discovery fits beautifully with the number of dark objects we expected to find, but every new detection helps refine or challenge our theories.”

He added, “Having found one, the question now is whether we can find more and whether their number will still agree with the models.”