Share and Follow

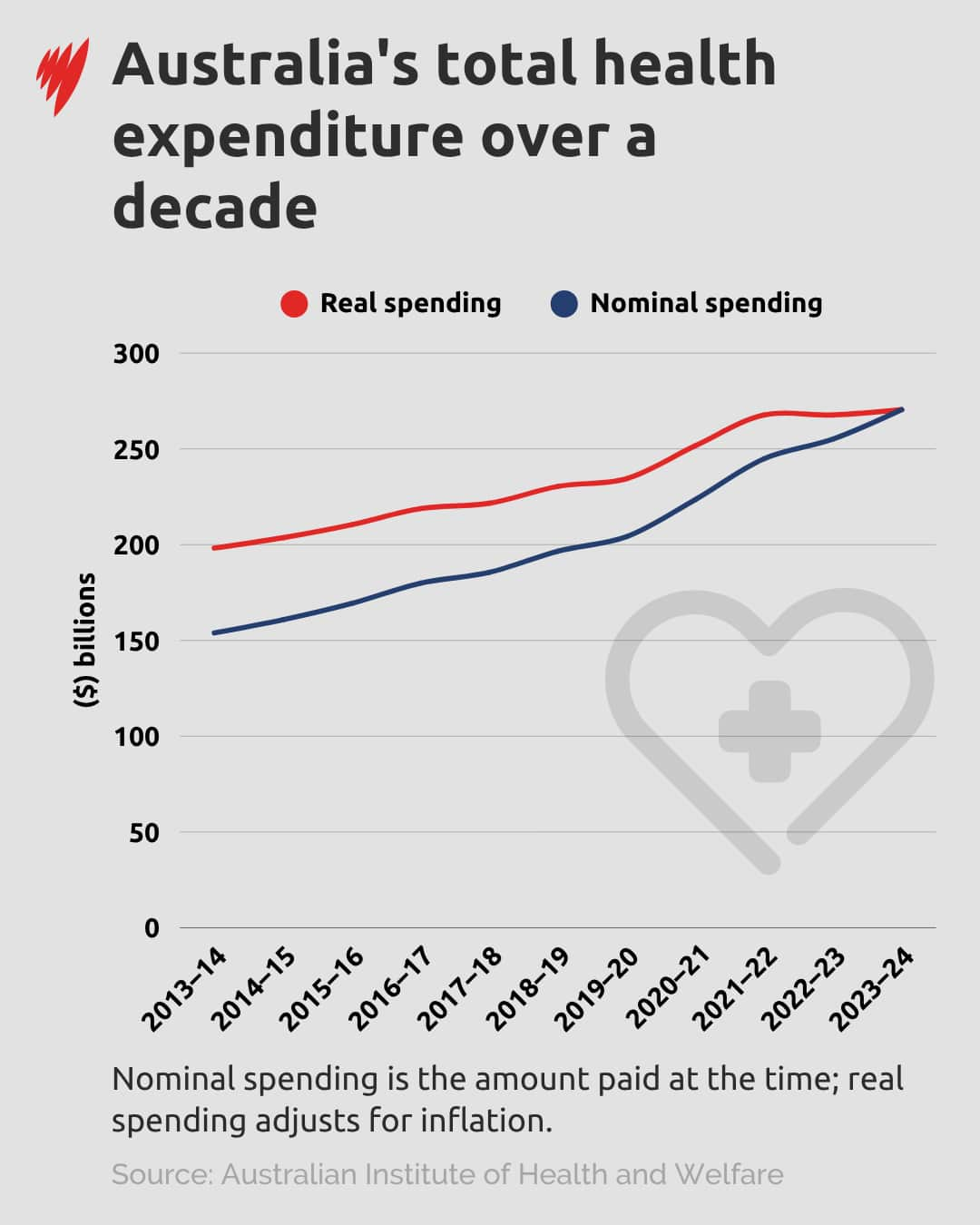

The proportion of government spending allocated to healthcare has shifted slightly, dipping from 17.1% in the fiscal year 2022-23 to 16.8% in 2023-24. This change indicates that health expenditure is rising at a slower pace compared to other sectors of government spending, according to a recent report.

In the financial year 2023-24, health-related expenses have transitioned into a post-pandemic phase, reaching a total of $270.5 billion. This figure represents 10.1% of the nation’s gross domestic product, reflecting the ongoing significance of healthcare in the country’s economy.

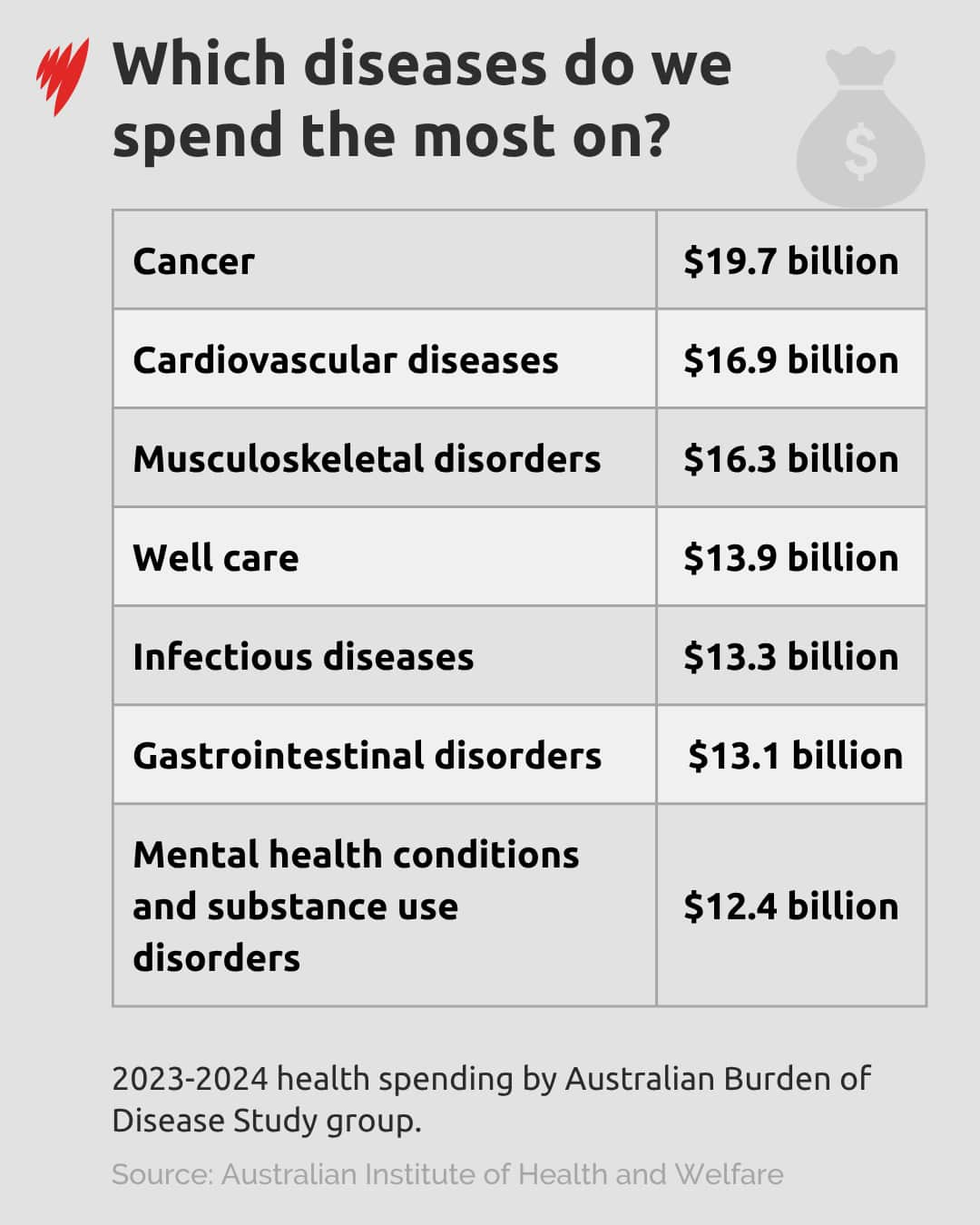

Data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) further dissects healthcare spending into 17 distinct categories related to diseases and injuries. Within these categories, expenditure rose from $170.2 billion in the previous year to $180.4 billion in 2023-24.

The difference between this sum and the overall health spending can be attributed to $73.9 billion allocated to non-treatment-related expenses. These include administrative costs and public health initiatives that do not correspond to specific disease treatments.

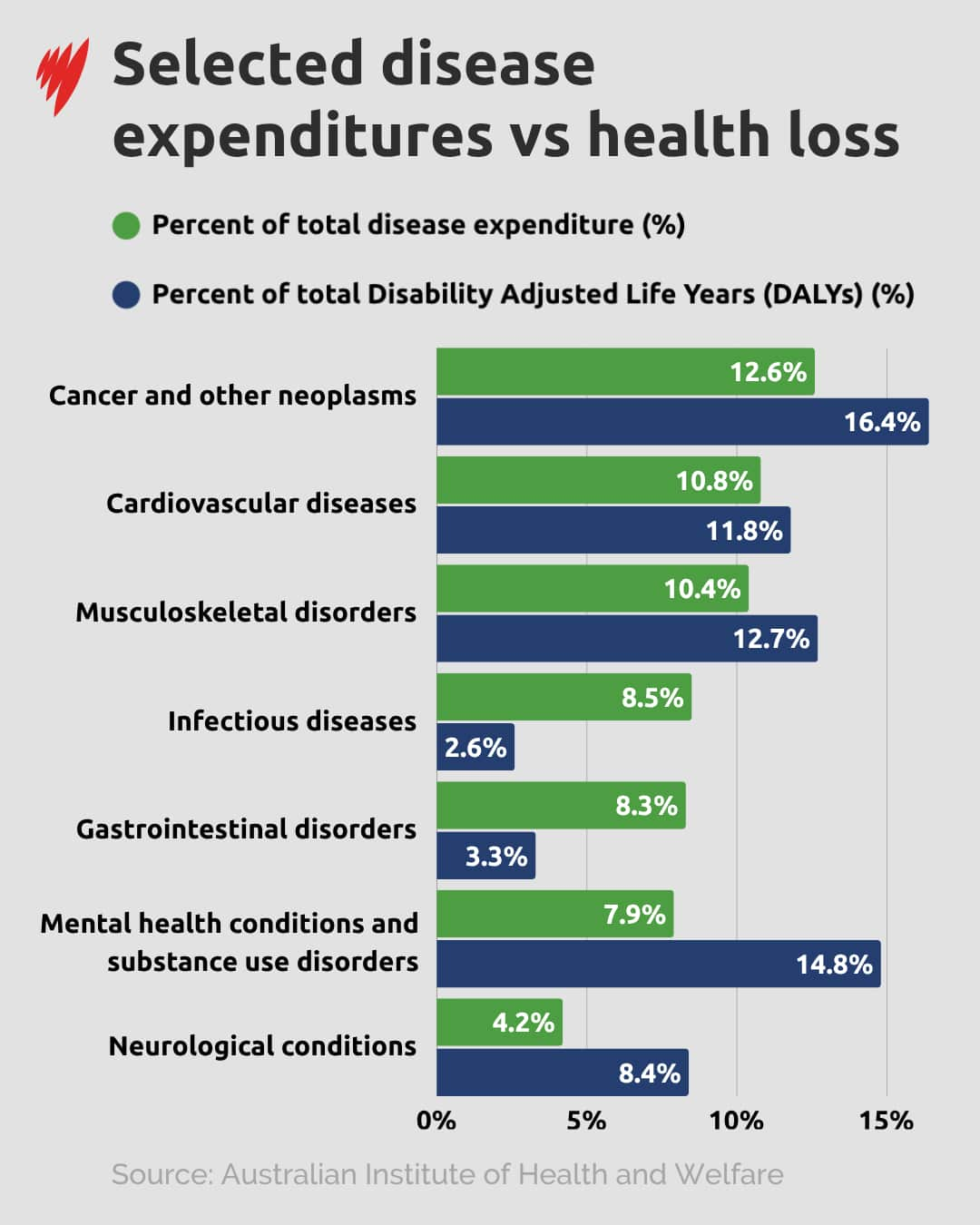

Disability-adjusted life years, also known as health loss, is a metric calculated from the years of life people lose due to premature death or disability caused by illness or injury.

In 2023–24, cancer was the disease group with the highest spending ($19.7 billion), followed by cardiovascular diseases ($16.9 billion) and musculoskeletal disorders ($16.3 billion). Source: SBS News

In second and third place are cardiovascular diseases at $16.9 billion and musculoskeletal disorders at $16.3 billion.

Cancer, cardiovascular diseases and musculoskeletal disorders have been the top three spending groups in all but one year since 2013-14.

The AIHW report notes there can be many reasons why certain disease categories have steeply divergent costs and spending levels.

Cancer was the disease group with the highest disease burden in Australia in 2024, accounting for 16.4 per cent of total disability-adjusted life years. Source: SBS News

“In cases where a particular disease has relatively high human cost but low spending, it does not necessarily mean that health spending should be increased,” the authors write.

They only include spending within the healthcare sector, but the AIHW notes that the costs of disease extend far beyond this into people’s lives.

What’s killing us?

Coronary heart disease was the biggest underlying killer of men, accounting for 10.8 per cent of deaths, while dementia was fatal to most women, accounting for around 12.2 per cent of deaths in that year.