Share and Follow

An Antarctic glacier has experienced an unprecedented reduction, shrinking by almost 50% in just two months, marking the fastest retreat ever documented. This rapid change could have significant consequences for global sea level rise.

The Hektoria Glacier, comparable in size to the Australian city of Newcastle, is located on the Antarctic Peninsula—a narrow mountain range extending from the continent like a thumb towards South America. This region is one of the most rapidly warming areas on Earth.

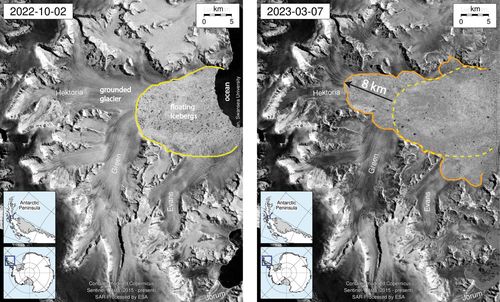

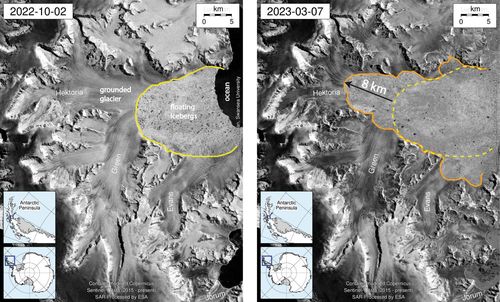

Typically, grounded glaciers like Hektoria, which are anchored to the seabed rather than floating, retreat only a few hundred meters annually. However, between November and December 2022, Hektoria retracted by an alarming 8 kilometers, as revealed in a study published in the journal Nature Geoscience.

“The rate of retreat is astonishing,” remarked Ted Scambos, a senior research scientist at the University of Colorado Boulder and co-author of the study. “It’s simply extraordinary.”

Gaining insight into the reasons behind this phenomenon is crucial; should larger glaciers undergo similar rapid retreats, the effects on sea level rise could be catastrophic, the authors warned in a statement accompanying their findings.

Antarctica holds enough ice to raise the global sea level by about 60 metres.

Hektoria’s near demise was discovered by chance. Researchers had been surveying the bay where it is located for a separate study. They were keeping a close eye on the area’s “fast ice” – sea ice fastened to land that doesn’t move with the wind or tides – believing it was about to break off and float out to sea.

As Naomi Ochwat, a study co-author, studied the data, she noticed Hektoria had lost an enormous amount of ice over a very short period.

She and her co-authors started to dig into what was happening, looking at satellite images and data from flyovers.

They identified several steps that led to Hektoria’s rapid retreat. In 2011, the bay filled with fast ice, stabilising the glaciers around it, allowing them to advance into the bay and form thick, floating ice tongues. In 2022, this fast ice broke out of the bay, destabilising the glaciers, causing them to lose their ice tongues and retreat.

The reason Hektoria fell apart much faster than its neighbouring glaciers was due to what lay beneath it, the scientists found.

Hektoria rests on an ice plain, where sliding ice glides over flat sediment on the seabed. Ice plains can prompt fast retreat because as the glacier thins, the ice starts to rise up and water pushes underneath into its crevasses, exerting pressure and causing large slabs to break off – in a process called calving.

As one iceberg calves, it exposes the glacier behind it to the same pressures and calving happens again. Scambos likens the process to “dominoes toppling backwards, their feet slipping out from under them, one after the other.”

This kind of ice plain melting has happened before. Models show that between about 15,000 and 19,000 years ago, during a period of warming that ended the last Ice Age, glaciers with ice plains retreated hundreds of metres a day.

But “we hadn’t seen it play out live before, certainly not at this rate,” Ochwat said.

Hektoria’s retreat was heavily influenced by climate change, she added. The loss of sea ice in the ocean next to Hektoria, believed to have been driven by ocean warmth, allowed wave swells to reach the fast ice and break it up, leaving the glacier exposed to ocean forces.

As climate change accelerates, “we are likely to see more reductions of sea ice in this region,” said Bethan Davies, a glacial geologist at Newcastle University in the UK who was not involved in the study. This could result in other glaciers losing the sea ice that currently buttresses them, she told CNN.

Hektoria is a relatively small glacier by Antarctic standards, and its partial demise would not cost the planet much in terms of sea level rise, Scambos said.

However, “it’s a smaller cousin to some truly gigantic – I mean size of the island of Britain – glaciers in Antarctica that could conceivably go through the same process, as this whole evolution of the ice sheets on earth evolves with global warming,” he said.

The next stage is to better establish which areas in Antarctica are vulnerable to the same process. If a huge glacier were to disintegrate quickly, “it means that we might have a step change in sea level rise,” Ochwat said.