Share and Follow

Blue Origin achieved a significant milestone on Thursday with the successful launch of its second New Glenn rocket, dispatching two small NASA satellites on an ambitious journey to Mars. The mission’s aim is to gather invaluable data on how the sun has gradually stripped away the once-dense atmosphere of the red planet.

The New Glenn rocket, standing at an impressive 321 feet, represents a crucial element of Jeff Bezos’ expansive vision for space exploration through Blue Origin. At precisely 3:55 p.m. ET, the rocket’s seven methane-fueled engines came to life, propelling the massive booster into the sky with a powerful 3.8 million pounds of thrust, creating a breathtaking spectacle.

This launch was originally scheduled for earlier in the week but faced delays due to adverse weather conditions both on Earth and in space. A particularly intense solar storm had bombarded Earth’s atmosphere with a surge of high-energy radiation, posing potential risks to the rocket and its onboard instruments.

Fortunately, conditions improved by Wednesday, allowing for a successful launch. Blue Origin’s team members, stationed a safe distance from the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, erupted in cheers and applause as the rocket ascended, with the thunderous roar of its engines echoing across the Space Coast moments later.

This mission follows the New Glenn’s inaugural flight last January, which successfully delivered a Blue Origin payload into orbit. However, the attempt to land the reusable first stage on an offshore platform, aptly named after Bezos’ mother Jacklyn, was unsuccessful. This latest mission marks another step forward in refining and perfecting the technology for future endeavors.

The launch came three days late due to stormy weather on Earth and in space, where a powerful solar storm buffeted Earth’s atmosphere with a torrent of high-energy radiation that could have caused electrical problems with the rocket or its payloads.

The storm had abated by launch time Wednesday, and Blue Origin employees, looking on from viewing sites several miles from the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station launch pad, cheered and applauded as the booster climbed skyward, followed moments later by the booming roar of its engines sweeping across the Space Coast.

Blue Origin

The New Glenn’s maiden flight last January successfully boosted a Blue Origin payload into orbit, but the reusable first stage failed in its attempt to reach an offshore landing ship, named after Bezos’ mother Jacklyn.

The 188-foot-tall first stage launched Wednesday, nicknamed “Never Tell Me The Odds,” featured a variety of upgrades to improve performance. This time around, the big rocket flew itself to an on-target touchdown, prompting more cheers and applause from Blue Origin workers.

Much like returning SpaceX Falcon 9 rockets, the larger New Glenn booster will be hauled back to Port Canaveral and, depending on its condition, be refurbished and readied for use on an upcoming New Glenn flight.

Spaceflight Now/Blue Origin

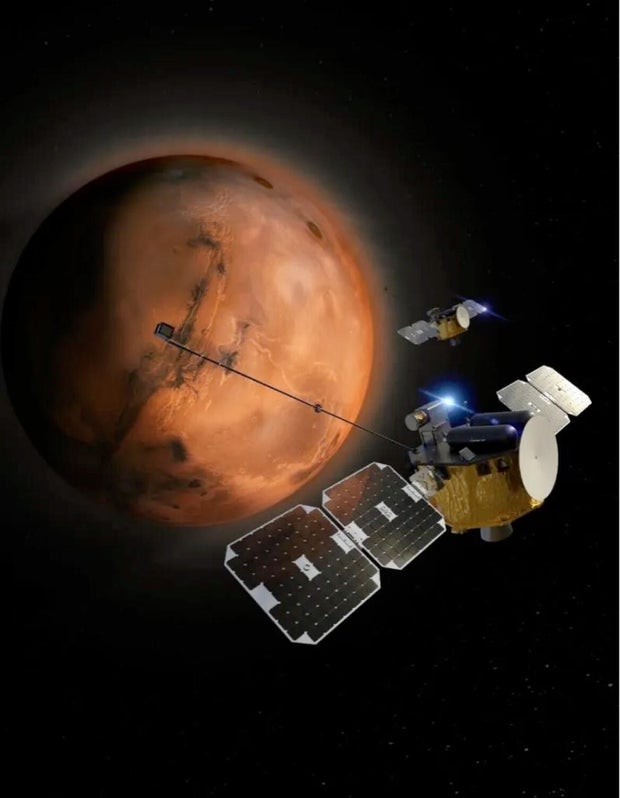

The second stage, meanwhile, pressed ahead, carrying out two firings of its twin engines to reach the planned Earth-escape trajectory. Thirty-three minutes after liftoff, the ESCAPADE satellites were released to fly on their own.

The NASA-sponsored payload, managed by the University of California, Berkeley, Space Sciences Laboratory, is made up of two small, low-budget satellites known as Blue and Gold that make up the heart of the ESCAPADE mission. The acronym stands for Escape, Plasma Acceleration and Dynamics Explorers.

The probes were built for UC Berkeley by Rocketlab under a NASA program intended to develop lower-cost, fast-track planetary missions.

ESCAPADE cost $107.4 million, a bargain compared to the cost of more traditional, more sophisticated planetary spacecraft that can cost hundreds of millions to well over a billion dollars each.

The ESCAPADE probes were originally expected to hitch a ride to Mars a few years ago with NASA’s Psyche asteroid probe. But for a variety of reasons, the Mars satellites mission ultimately ended up on New Glenn’s second flight.

Mars launch windows typically open every two years when Earth and the red planet reach favorable positions in their orbits to permit direct flights using current rockets. The next such window opens in 2026.

UC Bereley/NASA

To make Wednesday’s New Glenn launch work in 2025, mission planners with Advanced Space LLC came up with an innovative flight plan, one that will take Blue and Gold longer to reach Mars but will enable more flexible trajectories for future missions.

The probes were deployed on a trajectory that will carry them a million miles out, well past the moon’s orbit, where they will loiter for the next 11 months before heading back toward Earth.

Passing within 600 miles of Earth in November 2027, the ESCAPADE probes will make velocity-boosting gravity assist flybys, augmented by onboard propulsion, to finally head for Mars.

In all, the twin spacecraft will spend a full year in that initial kidney bean-shaped orbit out past the moon and back, and another 10 months in transit to Mars. The probes won’t reach the red planet until September 2027.

“We are using a very flexible … approach where we go into a loiter orbit around Earth in order to sort of wait until Earth and Mars are lined up correctly in November of next year to go to Mars,” said Robert Lillis, the principal investigator.

“This is an exciting, flexible way to get to Mars because in the future … we could potentially queue up spacecraft using the approach that ESCAPADE is pioneering” without having to wait for a planetary launch window to open, Lillis said.

While the ESCAPADE mission is modest compared to Mars rovers and more sophisticated orbiters, the probes are designed to answer key questions about the evolution of the Martian atmosphere.

Mars once had a global magnetic field like Earth, but its molten core, which powered that field, mostly froze in place long ago, leaving only patchy, isolated remnants of that once-protective field in magnetized deposits.

Without a protective global field like Earth’s, the Martian atmosphere faces a constant barrage of high-speed electrons and protons blown away from the sun and from dense clouds of charged particles erupting from powerful solar storms.

Working in tandem, first in the same orbit at different distances from each other and then from different altitudes, Blue and Gold will measure how the solar wind and energetic electrons and protons from solar storms interact with the Martian atmosphere.

Data from earlier Mars satellites showed the planet’s atmosphere is constantly being stripped by those interactions, but exactly how that happens over time is not fully understood.

“We really, really want to understand the interaction of the solar wind with Mars better than we do now,” Lillis said. “We know that atmospheric escape from Mars is a major driver for the evolution of the Martian climate. We know that Mars at least was episodically warm and wet for a couple billion years, but hasn’t been so for about 2 billion years or so. And we think atmospheric escape is a major reason for that.”

Blue and Gold will provide what amounts to a stereo view of those processes.

“If you only have one spacecraft, you can either measure what the sun is throwing at Mars, the so-called space weather environment upstream of Mars, or you can measure the conditions close to Mars in its upper atmosphere, where the atmosphere is escaping,” Lillis said.

“You can’t be in two places at once. But we can, because we have two spacecraft to do this. So we can really get that cause-and-effect at the same time. We’ve never had that before, and that’s really exciting,” Lillis said.