Share and Follow

Having dedicated over 30 years to training older adults, I’ve witnessed a recurring trend affecting countless individuals: the gradual decline of muscle mass. Starting around the age of 30, people typically experience a muscle mass reduction of about 3-8% per decade. However, this decline intensifies significantly after the age of 60. By the time many reach 70, they may have lost 30-40% of the muscle they once possessed during their peak physical years.

Why You’re Losing Muscle After 60 and What It Means for Your Independence

This phenomenon is medically termed sarcopenia. It’s crucial to understand the underlying causes of this condition. As we grow older, our bodies produce less protein and become less responsive to the protein intake from our diet. This means that even with a nutritious diet, our bodies don’t process protein as efficiently as they once did. Moreover, the natural decline in hormones, particularly testosterone and growth hormone, contributes to this issue. Coupled with a general decrease in physical activity as we age, these factors create an ideal environment for muscle loss.

The consequences of muscle loss are significant and multifaceted. Everyday tasks become increasingly challenging: rising from a seated position requires more effort, carrying groceries becomes strenuous, and opening jars might necessitate two hands instead of one. Climbing stairs can feel exhausting as legs become heavier. However, the most pressing concern is the increased risk of falls. Weak leg muscles hinder one’s ability to regain balance after a stumble, leading to potential trips to the emergency room for injuries that would have been minor in younger years.

Furthermore, weakened muscles can adversely affect balance, as they fail to provide the necessary rapid adjustments to maintain stability. A lesser-known effect of muscle loss is its impact on metabolism. As muscle mass decreases, so does metabolic rate, making it easier to gain weight even if dietary habits remain unchanged. Additionally, diminished muscle strength places extra stress on joints, accelerating conditions such as arthritis and contributing to joint pain.

Your balance suffers too because weak muscles can’t make the quick corrections needed to keep you steady. And here’s something most people don’t realise—losing muscle slows down your metabolism, making it easier to gain fat even when you’re eating the same amount. Weaker muscles also mean more strain on your joints, which accelerates arthritis and joint pain.

Why Chair Exercises Work Better Than You Think

Chair exercises work because they remove the biggest barrier I see with older adults—fear. When you’re holding onto or sitting on a stable chair, you feel safe. That confidence means people actually do the exercises instead of avoiding them.

The chair gives you support where you need it while still forcing your muscles to work hard. When you do a chair squat (sitting down and standing up), you’re lifting your entire body weight against gravity. That’s proper resistance training, not some watered-down version. Your muscles don’t know the difference between a gym squat and a chair squat—they just know they’re working.

We can also progress chair exercises in ways that suit different fitness levels. Someone who hasn’t exercised in years can use the chair for heavy support. Someone stronger can use it for light balance only. This adaptability means you’re not stuck doing the same easy routine forever—you can keep challenging your muscles as they get stronger.

The other thing I love about chair exercises is they train the exact movements we need for daily life. Standing up from a chair, stepping up, reaching overhead while staying stable—these aren’t gym exercises, they’re life exercises. When your muscles get stronger doing these movements, everything in your day gets easier immediately.

Chair Squats (Sit-to-Stands)

Which muscles does it build:

- Your quadriceps (front of thighs) do most of the work

- Your glutes (buttocks) and hamstrings (back of thighs) kick in as you stand

- Your core muscles stabilise you through the movement

- Your calves help with balance

This is the single most important exercise for older adults. It directly builds the strength you need to get off the toilet, out of the car, up from the sofa.

How to do it:

- Sit in your chair with feet flat on the floor, hip-width apart

- Your knees should be roughly over your ankles, not pushed forward

- Place your hands on your thighs or cross them over your chest

- Lean forward slightly from your hips (don’t round your back)

- Push through your feet and stand up fully

- Lower yourself back down with control—don’t just drop into the chair

- Tap the seat lightly and immediately stand back up

Start with 8-10 repetitions. When that feels manageable, aim for 3 sets with a minute rest between.

Avoid these mistakes:

- Don’t use momentum by rocking back and forth—this defeats the purpose

- Don’t let your knees cave inward as you stand (keep them in line with your toes)

- Don’t hold your breath—breathe out as you stand up

- Don’t stand up too fast if you feel dizzy—take it slower

- Don’t use your hands to push off your thighs unless you absolutely need to (we want your legs doing the work).

RELATED: 5 Chair Moves That Slim Your Waist Faster Than Crunches After 50

Seated Leg Extensions

Which muscles does it build:

- Your quadriceps (front thigh muscles)

- Your hip flexors get some work too

- Your core stabilises your torso

This exercise is brilliant for people who find standing exercises too difficult at first. It builds strength in the exact muscles you need for walking and climbing stairs.

How to do it:

- Sit upright in your chair with your back supported

- Your feet should be flat on the floor to start

- Hold the sides of the chair for stability

- Straighten one leg out in front of you until it’s parallel to the floor (or as straight as you can manage)

- Hold for 2-3 seconds at the top

- Lower your foot back down with control

- Complete all reps on one leg before switching

Start with 8-10 reps per leg. Work up to 3 sets.

Avoid these mistakes:

- Don’t kick your leg up with momentum—lift it smoothly

- Don’t arch your lower back as you lift (keep your core engaged)

- Don’t lock your knee joint hard at the top (keep it slightly soft)

- Don’t let your heel drop as you extend (flex your foot so toes point up)

- Don’t lean back in the chair—stay upright

Seated Marching

Which muscles does it build:

- Your hip flexors (muscles that lift your knee)

- Your quadriceps

- Your core muscles (particularly the lower abs)

- Your lower back stabilisers

This exercise builds the strength you need for walking and climbing stairs. I’ve seen it make a massive difference to people who shuffle when they walk.

How to do it:

- Sit towards the front of your chair (not right at the edge though)

- Sit upright with your back straight, not leaning on the backrest

- Place your hands on the chair beside your hips for support

- Lift your right knee up as high as comfortable (aim for hip height eventually)

- Lower it back down with control

- Immediately lift your left knee

- Keep alternating in a marching rhythm

Start with 20 total lifts (10 each leg). Build up to 3 sets of 20.

Avoid these mistakes:

- Don’t lean back as you lift your knee (this makes it easier but less effective)

- Don’t use momentum to swing your leg up

- Don’t hold your breath—breathe naturally throughout

- Don’t lift one leg higher than the other (keep the movement even)

- Don’t let your upper body rock side to side

Chair Push-Ups (Armchair Press-Ups)

Which muscles does it build:

- Your triceps (back of upper arms)

- Your shoulders

- Your chest muscles

- Your core stabilisers

This exercise builds the upper body strength you need to push yourself up from a chair or out of bed. It’s also brilliant for improving your ability to catch yourself if you start to fall.

How to do it:

- Sit upright in a sturdy chair with armrests

- Place your hands firmly on the armrests

- Push down through your hands to lift your bottom slightly off the seat

- You don’t need to lift high—even an inch counts

- Hold for 2-3 seconds

- Lower yourself back down with control

Start with 5-8 reps. Work up to 3 sets of 10.

Avoid these mistakes:

- Don’t shrug your shoulders up by your ears (keep shoulders down)

- Don’t hold your breath—breathe out as you push up

- Don’t lean to one side (push evenly through both arms)

- Don’t attempt this if your chair rocks or has wheels

- Don’t worry if you can’t lift off the seat at first—just pushing hard builds strength

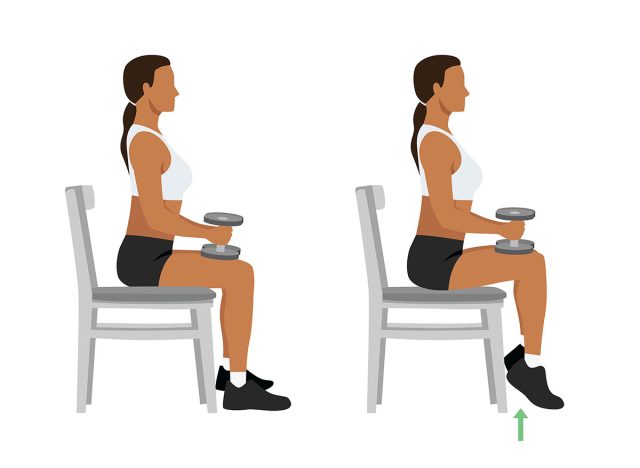

Seated Heel Raises

Which muscles does it build:

- Your calf muscles (gastrocnemius and soleus)

- The small stabilising muscles in your feet and ankles

Strong calves are essential for balance and walking. This exercise is particularly important because calf strength directly affects your ability to catch yourself when you stumble.

How to do it:

- Sit upright in your chair with feet flat on the floor

- Your knees should be at 90 degrees

- You can hold the sides of the chair lightly for balance

- Lift both heels off the floor, rising up onto the balls of your feet

- Go as high as you can

- Hold at the top for 2 seconds

- Lower your heels back down with control

Start with 15-20 reps. Build up to 3 sets of 20.

Avoid these mistakes:

- Don’t let your knees push forward as you lift (keep them still)

- Don’t roll onto the outside edges of your feet (stay balanced)

- Don’t rush the movement—control matters more than speed

- Don’t tense your upper body (keep shoulders relaxed)

- Don’t skip the hold at the top—that’s where the strength builds

What Kind of Chair You Need (Hint: Probably the One You’re Sitting On)

A regular kitchen or dining chair works perfectly. You don’t need anything special. In fact, I prefer people use their everyday chairs because that’s what they’ll have access to when they need it.

The chair needs to be:

- Stable (no wheels, no rocking)

- The right height (when you sit, your knees should be at roughly 90 degrees with feet flat on the floor)

- Heavy enough that it won’t slide or tip

- Without arms for most exercises (though you’ll need arms for chair push-ups)

Your standard wooden or upholstered dining chair ticks all these boxes. If your chair is too high and your feet don’t reach the floor properly, put a thick book or yoga block under your feet. If it’s too low (your knees are higher than your hips), add a firm cushion to the seat.

Avoid:

- Office chairs with wheels

- Folding chairs (they can collapse)

- Bar stools or very high chairs

- Soft, deep sofas or armchairs (you sink too far down)

- Anything rickety or unstable

For chair push-ups specifically, you’ll want a sturdy chair with armrests. A dining carver chair or solid armchair works well.

How Often You Should Do These Exercises and How Long Each Session Takes

Three times per week is the sweet spot. Monday, Wednesday, Friday works well, or Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday. The key is having at least one rest day between sessions—this is when your muscles actually rebuild and get stronger.

Each session takes 15-20 minutes once you’re doing all five exercises. When you’re starting out and just doing one set of each, you’ll be done in 10 minutes. As you progress to three sets with proper rest periods, plan for 20 minutes.

Here’s what a typical session looks like:

- Chair squats: 3 sets of 10 reps (3 minutes)

- Seated leg extensions: 3 sets of 10 reps per leg (4 minutes)

- Seated marching: 3 sets of 20 total (3 minutes)

- Chair push-ups: 3 sets of 8 reps (2 minutes)

- Seated heel raises: 3 sets of 20 reps (3 minutes)

- Rest periods between sets: about 5 minutes total

Don’t train the same muscles on consecutive days. They need recovery time. If you want to exercise more than three times per week, do something different on the other days—go for a walk, do some stretching, work on balance exercises.

I’ve seen people try to do these exercises every single day thinking more is better. It’s not. They end up tired, sore and discouraged. Three times per week, done consistently, beats seven days per week done until you burn out.

What Results You Can Realistically Expect and When You’ll Notice Them

You’ll start to feel different before you see changes. Within a couple of weeks, everyday tasks will start to become noticeably easier—standing up doesn’t require pushing with your hands, going upstairs doesn’t leave you winded and your shopping feels lighter. Your nervous system is getting better at activating your existing muscle fibres.

Weeks 6-8 your muscles will start feeling firmer. Your legs feel more solid. This is when the actual muscle growth starts. Tasks that were really tough at the start now feel routine.

By 12 weeks (three months), you’ll see measurable changes. Your trousers might fit differently around your thighs. You’ll stand taller. Friends might comment that you’re moving better. This is proper muscle rebuilding.

Realistically, here’s what I see with most people over 60 who stick with it:

- A 10-15% strength increase in the first 8 weeks

- A 20-30% strength increase by 6 months

- Noticeable muscle size increase by 4-6 months (though this varies with age and nutrition)

The initial improvements are more dramatic the older you are (or the longer it’s been since you exercised). I’ve worked with people 70+ who doubled leg strength in 6 months because their initial baseline was so low.

What matters most is that you’ll regain independence. The things you stopped doing because they were just too hard become possible again. Getting up off the floor. Gardening for an hour or two. Playing with your grandkids. Walking without being scared you’ll fall.

Consistency is key. Three sessions a week, every single week you can. Missing the odd week here or there is fine, but if you only do the workouts when you feel like it you won’t see results. Our muscles need stimulus regularly to grow. Think of it like taking medicine—it only works when you do what’s prescribed.