Share and Follow

“I like to think of myself as a former otaku now,” she shared with SBS News.

In 2024, a significant milestone was reached in the anime industry as international revenues from anime production surpassed domestic sales for the second consecutive year. In response, the Japanese government unveiled its New Cool Japan Strategy, targeting a substantial increase in global content-related business, aiming for a $198 billion market by 2033.

In Australia, fans eagerly gather at conventions such as Oz Comic Con, drawn by the allure of anime and manga attractions.

As Australia prepares to reassess its National Cultural Policy next year, there is growing advocacy for the government to take a leaf out of Japan and South Korea’s book, enhancing the global reach of Australian-produced content.

Australia records ‘worst’ trade deficit in content

In a submission to the federal government’s 2022 cultural policy review, ANA presented analysis that showed that for every $1 Australia exports in creative goods, $8 is imported from other countries.

In 2023, Arts Minister Tony Burke launched Creative Australia as part of Labor’s National Cultural Policy, Revive. Source: AAP / Jane Dempster

Fielding says the National Cultural Policy launched in response in 2023 still had “limited focus on international [exports] within that”.

“I think that probably Australia has had a long journey to really developing and appreciating our own cultural and creative industries, and … part of the lag for us as a nation has been maturing and understanding that we have excellent cultural and creative contributions to make to the world.

I think it is time for us to really step forward as a mature nation and take those steps.

A spokesperson for the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Communications and the Arts says artists can also access funding to explore international collaboration and development via Creative Australia and Screen Australia.

“That doesn’t need to be a comprehensive mapping.”

Australia’s soft power problem

Australia’s creative and cultural exports were identified in a 2017 foreign policy white paper as potential avenues for the nation to exert soft power — which is the ability to attract and influence other countries through non-military measures — along with international education, tourism and migration.

A spokesperson for the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade told SBS News the department “works closely with Australia’s world-class cultural sector to showcase our creativity, values and diversity internationally”.

Despite its global fame, Australia has little involvement with Bluey’s international distribution and its success, as it’s operated by BBC Studios. Source: AAP / Bianca De Marchi

“Our cultural exports — from film and television to literature, music, design and art — are among the best in the world. They tell the story of who we are and play an important role in strengthening Australia’s voice and relationships,” the spokesperson said.

What can Australia learn from its Asian allies?

“[The rise of anime] happened organically, picked up by the Japanese consumers first, then picked up by the foreign consumers,” he tells SBS News.

The whole movement happened outside of government control.

According to Kimura, the growing revenue from international consumers, coupled with the huge economic losses from piracy, has pushed the Japanese government to consider a new economic strategy to maximise profits from the industry.

“With major changes taking place in the environment surrounding [Cool Japan], the soft power of [Cool Japan] is an extremely potent means of ensuring Japan can maintain its presence and influence on the global stage,” the 2019 Cool Japan Strategy paper reads.

‘A tool of global influence’

Since then, successive South Korean governments — whether conservative or progressive — have launched initiatives to support the creative sector’s development.

“Australia could adopt a similar whole-of-government framework linking creative funding with trade, diplomacy and education, turning its artistic strengths into a cohesive and globally recognisable cultural brand,” she says.

To amplify soft power, treat artists well first

But simply having a strong cultural sector doesn’t necessarily elevate soft power, says Roald Maliangkay, a professor of culture, history and language at the Australian National University’s College of Asia and the Pacific.

During his Golden Globe Award speech, South Korean director Bong Joon Ho (middle in the second row) famously claimed that once audiences “overcome the one-inch-tall barrier of subtitles”, they would be introduced to a new world. Source: AAP / EPA / Kim Hee-chul

He says international consumers often view a country’s cultural products through the lens of their impression of the nation.

“We do not have a more modern culture that people would fondly associate with. [Also,] South Korea and Japan both have a very unique language,” he says.

One of the things that people have really enjoyed when they listen to K-pop or watch Korean TV dramas is the idea that by learning a little bit, you gain some cultural capital.

Kimura says the Japanese government offers little support for individual anime creators.

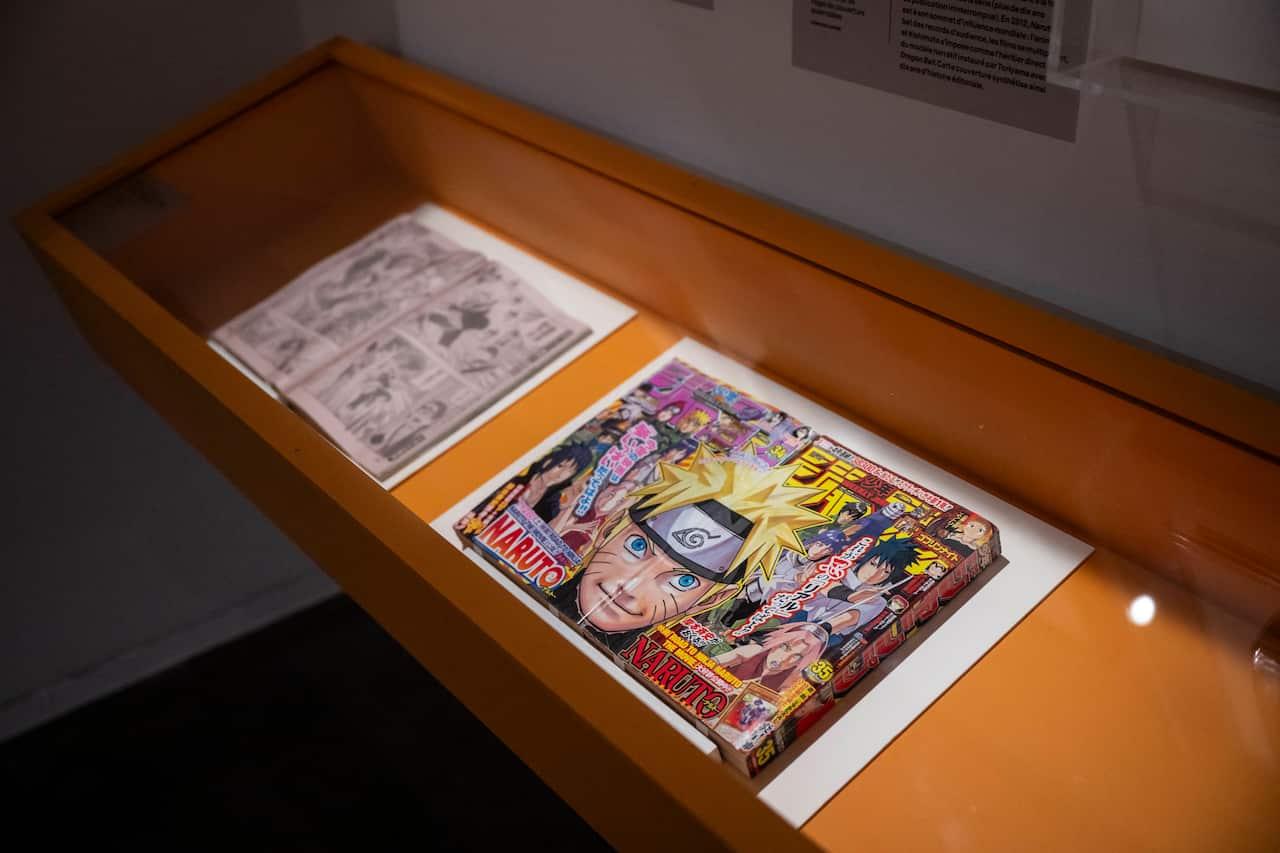

Individual artists and creators have played key roles in the huge success of Japan’s anime sector, creating cultural icons that resonate with overseas audiences. Source: AAP / ABACA / PA / Blondet Eliot

“A lot of those people … are really, really low paid, and a lot [of them] do not see a promised future unless there’s a sacrifice made by the Japanese creators,” he says.

She also says South Korea’s heavy dependence on global streaming platforms has limited its control over revenue and cultural representation —- an issue that Australia’s music industry has long identified with platforms like Spotify.