This article contains references to self-harm and sexual assault.

At first glance, Sara Mashalian looks like she’s living a happy suburban life in Australia.

The 42-year-old lives with her partner, Ali Gharaei, in Sydney’s West and works as a dental assistant; Gharaei owns an IT business.

The pair are renovating their home and building a veggie patch in their backyard, complete with a classic Hills hoist.

The Australian government has decided against allowing Mashalian to settle permanently in the country due to the circumstances surrounding her arrival.

“I left Iran in 2013 after becoming a Christian. Converting from Islam is considered a crime punished by death. And it was no longer safe for me to stay,” she tells SBS News.

“I came to Australia by boat. The journey was far more terrifying than anything I could have imagined: extremely dangerous, traumatic, and full of fear,” Mashalian says.

“But we didn’t have any choice.”

Under the policy, any asylum seeker arriving by boat and sent to mandatory offshore detention would never be settled permanently in Australia.

It was a position then-prime minister Kevin Rudd said would deter people smuggling operations and unauthorised boat arrivals.

In her late twenties, Mashalian, along with her 56-year-old mother, made their way to Australia, only to be transferred first to Christmas Island and subsequently to Nauru. Here, they endured years in immigration detention.

The relentless anxiety and fear of their situation took a heavy toll on Mashalian’s mental health. She recounts enduring sexual harassment from staff within the detention center.

Mashalian describes limited access to clean water and adequate food, mouldy living quarters, and a polluted environment left behind by years of phosphate mining on the island.

“This experience inflicted long-lasting physical and psychological harm on both me and my family,” Mashalian shared. “I developed asthma, chronic neck and back pain, and anxiety. My mother’s health deteriorated significantly, leading to severe heart issues.”

“Sexual assault, constant trauma and toxins from phosphate [mining] made many people sick,” Mashalian says.

During their time in detention, her mother’s heart condition worsened, culminating in a heart attack when officials attempted to return them to Nauru.

Immigration detention trauma

Mashalian and her mother had to be medically evacuated from Nauru in 2015 and were transferred to detention facilities in Darwin and Brisbane for treatment.

Her mother had developed heart problems while in detention and suffered a heart attack when authorities tried to send the pair back to Nauru.

Sara Mashalian is picking tomatoes from her garden before heading to work as a dental assistant. Source: SBS News / Alexandra Jones

Mashalian recalls many other detainees also resorted to extreme measures to protest being forced to return to Nauru or Manus Island when they were deemed well enough.

Through tears, she describes some of the horror she witnessed in a Darwin detention centre.

“Every midnight, 2am or 3am, the immigration officer would come, [tie up] the hands and go put people [into vehicles] for travelling back to Nauru,” Mashalian says.

“One lady was pregnant, maybe three months … She cut it with a knife, her stomach. The baby’s come out.”

That’s few years ago but it stays in my mind, I feel it.

“And the kids cutting their hands and because they don’t want to go back [to Nauru]. And people crying loudly. They shoot the people’s leg. They keep them [up against] the wall,” Mashalian says.

The incident involving a pregnant woman was one of dozens of reports of self-harm at the Darwin detention facility at Wickham Point in 2015, and illustrative of a broader pattern of self-harm in offshore and onshore detention facilities.

Ali Gharaei (left) and Sara Mashalian say the uncertainty around Mashalian’s visa situation has led them to put off having children. Source: SBS News / Alexandra Jones

“Can you clean my mind?” Mashalian says, referring to memories that still haunt her a decade later.

Lost chances

Mashalian and her mother were eventually sent to community detention in Sydney before being released in 2018.

Years later, despite being in a registered relationship with an Australian citizen and working and paying tax in Australia, Mashalian still must apply for a new temporary bridging visa every six months.

“Every time immigration calls me, I get too much stress,” she says.

“Every six months, my visa expires. Every six months, my Medicare expires. For more than three months, I don’t have Medicare. [I’m] not allowed to study. Even I can’t buy a mobile SIM card.

“I can’t drive in Australia because if I have even one penalty … immediately immigration can cancel my visa.”

Mashalian says the constant anxiety she and her mother experience in “visa limbo” has caused them both mental and physical health issues.

“Immigration exactly says to me, ‘if we call you, immediately you should answer your phone’ If I [am in the] toilet and don’t answer my phone, immigration can cancel my visa. Yes. Just for not answering the phone,” she says.

“Last time when they called my mum to renew the visa, she had [another] heart attack.”

Mashalian says she also put off having children, wanting to ensure she had security and visa safety in Australia before doing so.

She fears she may have lost her chance to become a mother.

“I’d like to be having children,” she says.

“But how can I imagine having children? I am 42 years old. I have a limited time, I can be a mother.”

No permanent pathway for ‘transitory persons’

Mashalian and her mother, along with around 900 other former detainees, are deemed “transitory persons” under Australia’s immigration laws.

The cohort has no pathway to permanent visa status, despite many having family members or partners who are Australian citizens.

Ferdos, 23, who requested SBS News omit her surname, is part of that cohort.

She and her family also fled Iran in 2013 and sought asylum in Australia by boat. Ferdos was 10 years old at the time.

“Coming to Australia was the right choice even though the path was extremely difficult,” she says.

That experience was traumatising. No child should ever experience what we went through.

“After arriving, we were sent to offshore detention and first we spent 11 months in Christmas Island and then five years in Nauru detention centres,” Ferdos says.

Earlier this year, the 23-year-old wrote to Immigration Minister Tony Burke, several other federal ministers and her local member.

Ferdos, 23, says children like her who were sent to offshore detention have already suffered enough. Source: SBS News

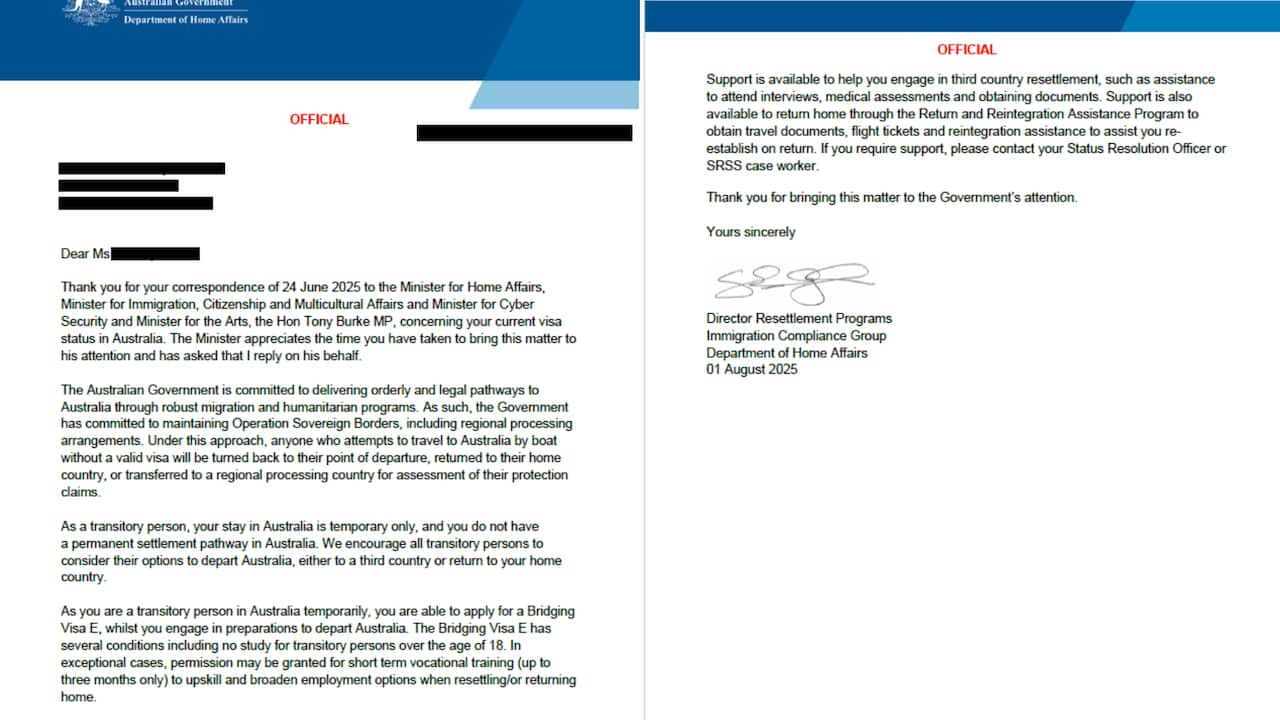

Ferdos received a response from an unnamed representative of the Department of Home Affairs’ Director Resettlement Programs Immigration Compliance Group, writing on behalf of Burke.

The letter reads: “As a transitory person, your stay in Australia is temporary only, and you do not have a permanent settlement pathway in Australia.”

“We encourage all transitory persons to consider their options to depart Australia, either to a third country or return to your home country.”

The letter encourages her to apply for a Bridging Visa E — a class of temporary visa offered to people to stay in Australia for a short period while preparing to depart. It also lists support services to help “engage in third country resettlement”.

For Ferdos and others who have now lived in Australia for nearly a decade, going home to face likely persecution or to another country is out of the question.

“It’s either you go back to your home country, or you choose a third country. But Nauru was the third country. I’ve spent five years there and I think I’ve done my time,” she says.

“Nauru took away my childhood and it is something that will stick with me for the rest of my life.”

The letter Ferdos received regarding her request for ministerial intervention from the Department of Home Affairs. Source: Supplied

Ferdos completed high school in Australia, despite missing out on five years of education between the ages of 10 and 15.

She’s now working as an employment specialist, helping other Australians apply for jobs.

“I work in the community sector delivering services and employment opportunities, and my job is all about transforming lives,” she says.

“It’s so beautiful seeing this country has all these opportunities while helping others achieve their goals and dreams.

“Unfortunately, my goals and dreams are on hold simply because I’m not recognised as a permanent resident or citizen.”

Ministerial intervention the only option

Laura John is an associate legal director at the Human Rights Law Centre, and Mashalian’s lawyer.

She’s among advocates pushing for ministerial intervention in so-called ‘legacy cases’ that remain unresolved.

“The Minister for Immigration already has the power to intervene and to grant Sara [Mashalian] a permanent visa and to grant all people who were in this group a permanent visa so they can fully rebuild their lives and live in safety and dignity here in Australia,” John tells SBS News.

“The problem here is that we have a government policy that was implemented over a decade ago that no longer reflects the practical reality of people’s lives.”

Associate legal director at the Human Rights Law Centre, Laura John, says “it’s time” for ministerial intervention in legacy offshore detention cases. Source: SBS News

In 2013, when Rudd announced the expansion of Australia’s offshore processing policy, he described it as a “very hard-line decision”.

Within seven weeks of its implementation, Rudd lost the election to Liberal leader Tony Abbott, who led the Liberal-National Coalition to victory with his ‘stop the boats’ campaign.

The campaign laid the groundwork for Operation Sovereign Borders, a policy of zero tolerance towards asylum seekers arriving by boat, then referred to by the government as “illegal maritime arrivals”.

But applications were only open to those who had arrived before Operation Sovereign Borders started on 18 September 2013, or who already held temporary protection visas (TPV) or safe haven enterprise (SHEV) visas.

Despite arriving in Australia before the cut-off, Mashalian and Ferdos were in offshore detention by September 2013, and never granted a TPV or SHEV.

John explains that Mashalian is also ineligible for a partner visa due to her status as a ‘transitory person’, despite her relationship having been formally registered.

The only visa option available is a bridging visa, which expires every six months and can be subject to processing delays, John says.

“During that period, technically [visa applicants are] not able to work. It means that you’re not able to consistently access Medicare, and it also means that you live under the constant fear that the government may require you to leave your family and the community that you’ve built in Australia,” she says.

These are people who work alongside us, whose children go to schools and childcare. These are people who are Australian in every sense of the way other than their visa status.

“It’s time for the minister to intervene and to grant people in this group permanent visas to accept what is already the case. They are Australian. This is their home, and they deserve to be able to stay here with their families.”

Speaking out

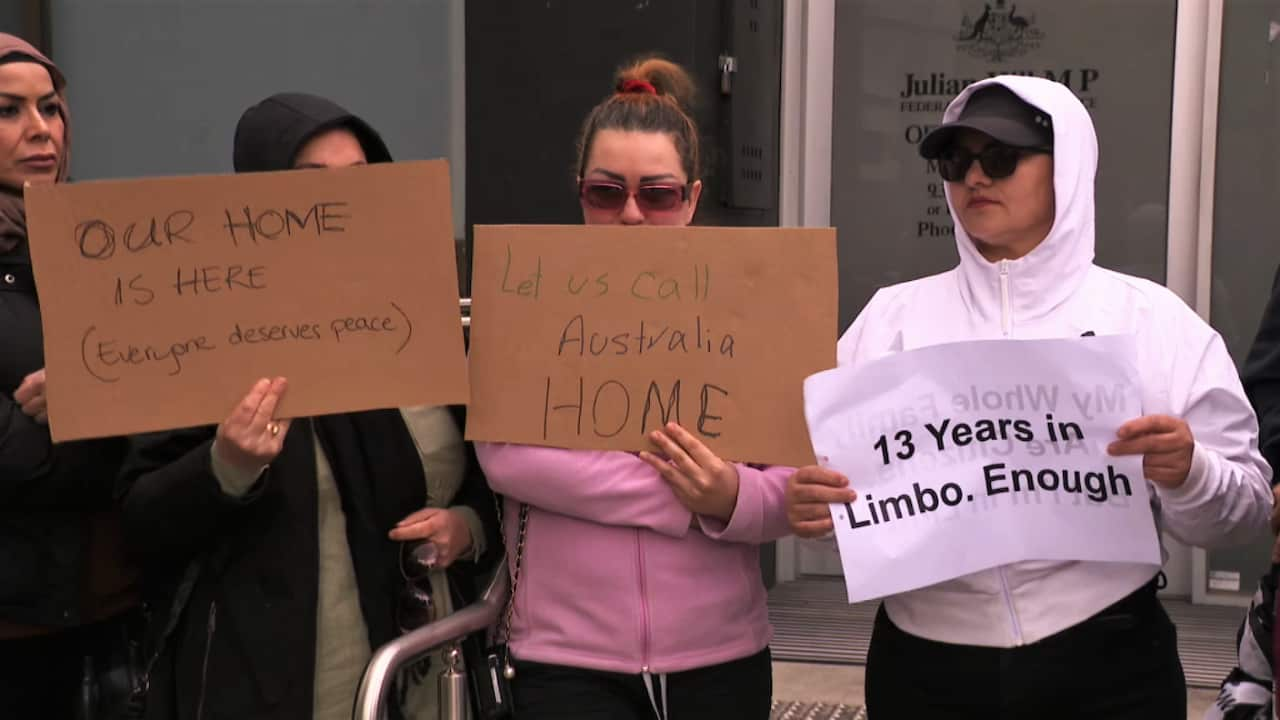

Mashalian is now leading a group of former detainees who have started protesting publicly as a last resort, in the hopes that the Australian government will listen to their stories and reassess their visa status.

In early November, the group held a demonstration outside the electorate office of Assistant Minister for Citizenship Julian Hill in Dandenong, Victoria.

Sara Mashalian (left) with her brother, mother and father in 2024. Her brother and father are Australian citizens. Source: Supplied

Among them were several children who were babies when they were sent to Nauru.

Hossam, 13, was one-year-old when he came to Australia with his family.

“My brother is ten now, he was born here and now he has citizenship, but the rest of my family here do not have citizenship,” Hossam says.

“We moved here to get a better life. I want to have the opportunity to call Australia home.”

Another young protester Amir, who is also 13, says he’s speaking out because he wants the government to hear his voice.

“I came here when I was ten months old. I have a little sister, she’s already got her citizenship [and] she’s 10 years old. I just want the government to give us a chance,” he says.

“We’ve already lived here for a while, and I think it’s only fair for us to live here longer and call this home.”

A spokesperson for Hill said: “The Federal Labor Government has provided permanent protection to over 20,000 genuine refugees whose lives were left in limbo for over a decade by the cruel policies of the previous Liberal Government.”

“Where a genuine refugee is eligible for permanent residency, most of the long-term outstanding cases involve complex identity or character issues.”

Protesters gathered outside the electorate office of Assistant Citizenship Minister Julian Hill in Dandenong, Victoria, in November. Source: SBS News

From her home back in Sydney, Mashalian says her message to Burke is simple.

“Please allow me to stay here permanently so I can live with safety and stability. I came to Australia seeking protection and peace,” she says.

“I just want to change to live a normal life, [to] study, work, and be with my family. I want to have children. I want to be relaxed without more stress. I want to contribute to Australia, not be trapped forever.”

I try to control it and not cry, but it’s very hard. Australia is my country, please Mr Tony.

A spokesperson for the Department of Home Affairs told SBS News in a statement: “The Australian Government is committed to resolving the transitory persons caseload temporarily in Australia through third country migration outcomes and continues to work with resettlement partners to identify resettlement opportunities.”

Sara Mashalian has been working as a dental assistant for around five years. Source: Supplied

“Transitory persons are encouraged to remain engaged in third country resettlement, notably with New Zealand, identify independent resettlement pathways or pursue voluntary return home.”

As at 30 June 2025, 1,531 resettlement outcomes have been achieved for transitory persons, including 1,115 to the United States and 309 to New Zealand, according to data from the Department of Home Affairs.

Australia’s offshore detention legacy and new Nauru deal

While former Nauru refugees like Mashalian and Ferdos protest their case, dozens of people remain in offshore detention facilities on Nauru and in Papua New Guinea, John says.

“As far as we’re aware, there are around 100 people who are still in Nauru, who have been subjected to offshore detention for the processing of their refugee claims,” she says.

“I say ‘as far as we know’, because this is an area where the government has shown no transparency, and the entire offshore regime operates under a veil of secrecy.”

John says there are around 30 to 40 people who have been “abandoned” in Papua New Guinea.

“From what we understand, people who are in Papua New Guinea are having difficulty even finding enough money to pay for basic food and health care,” she says.

“Australia’s offshore detention regime is a flawed and fundamentally problematic policy. It should never have been implemented in Australia.”

The Asylum Seeker Resource Centre says Australia’s policy of offshore detention has resulted in at least 14 deaths, while the Kaldor Centre for Refugees puts the figure at 21 since 2012.

John points out that the harms to the more than 4,000 people who survived systemic neglect and abuse in offshore detention have been well documented by United Nations bodies and human rights organisations in Australia and overseas.

Following the 2016 release of the Nauru files, which exposed thousands of incident reports detailing brutal and inhumane treatment and squalid living conditions, the issue gained international attention and became the subject of a Senate inquiry.

Now, the Australian government has signed a new $2.5 billion deal with the government of Nauru to send more than 350 former detainees there.

Those to be sent to Nauru are part of the so-called NZYQ cohort, a group who were released into the community after a 2023 High Court decision ruled they could not be held indefinitely in immigration detention.

“It is shocking that the Australian government is contemplating and is, in fact, expanding offshore warehousing in Nauru, rather than completely closing what we know has been a dark and terrible chapter in Australia’s history,” John says.

Former Nauru refugees, including Ferdos, say they’re horrified to hear people are still being sent to Nauru.

“Hearing, reading about all of this, I just feel fear. It brings back so many memories and no child, no person should ever experience what we went through,” she says.

It really upsets me, because offshore detention centres simply take away people’s lives. It’s just not right in any sense.

Readers seeking crisis support can ring Lifeline on 13 11 14 or text 0477 13 11 14, the Suicide Call Back Service on 1300 659 467 and Kids Helpline on 1800 55 1800 (for young people aged up to 25). More information and support with mental health is available at beyondblue.org.au and on 1300 22 4636.

If you or someone you know is impacted by sexual assault, call 1800RESPECT on 1800 737 732, text 0458 737 732, or visit 1800RESPECT.org.au. In an emergency, call 000.