Share and Follow

ATLANTA (AP) — An exhibit in Atlanta is now showcasing a historical marker from a 1918 lynching site, which has suffered repeated vandalism over the years. The display opens to the public on Monday.

The marker commemorates an event that some in rural southern Georgia wish to forget: the brutal murder of Mary Turner by a white mob. Turner had vocally demanded justice for her husband Hayes Turner and at least 10 other Black individuals who had been lynched.

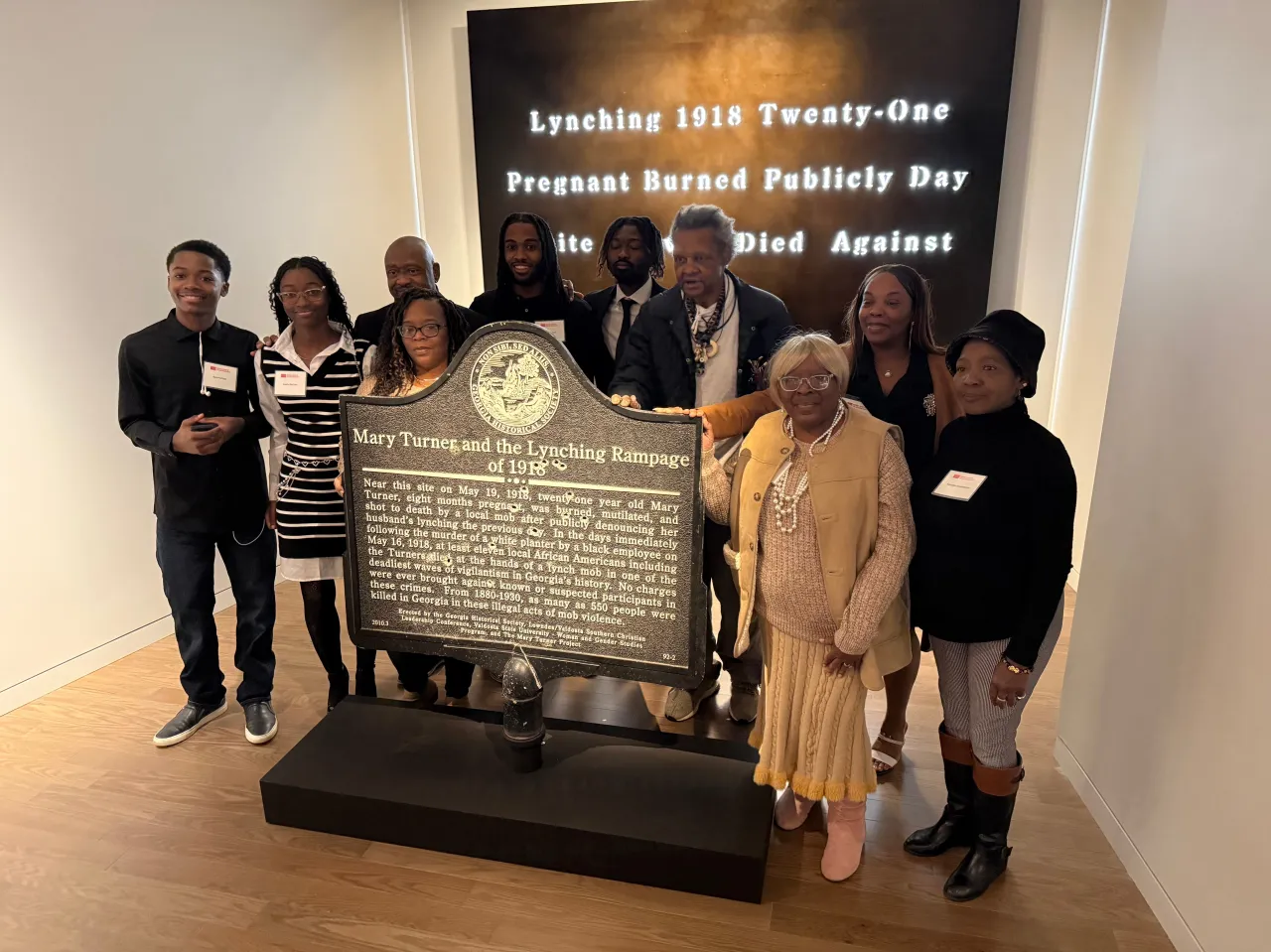

Marred by bullet holes and damage from an off-road vehicle, the Georgia Historical Society marker bears the grim details: “Mary Turner, eight months pregnant, was burned, mutilated, and shot to death by a mob after publicly denouncing her husband’s lynching the previous day. … No charges were ever brought against known or suspected participants in these crimes. From 1880-1930, as many as 550 people were killed in Georgia in these illegal acts of mob violence.”

Now, each bullet-riddled word is projected onto a wall, accompanied by the voices of Turner’s descendants spanning six generations.

“I’m glad the memorial was shot up,” expressed Katrina Thomas, Turner’s great-granddaughter, after viewing the exhibit at the National Museum for Civil and Human Rights. “Millions will now learn her story. Her voice persists through the years, proving that history never truly vanishes. It continues to resonate and expand.”

Americans learned about these lynchings in 1918 because they were investigated in the immediate aftermath by Walter White, who founded the Georgia chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and would become an influential voice for civil rights nationwide. A light-skinned Black man who could pass for white, he interviewed eyewitnesses and provided names of suspects to the governor of Georgia, according to his report in the NAACP’s publication, The Crisis.

Georgia was among the most active states for lynchings, according to the Equal Justice Initiative ’s catalog of more than 4,400 documented racial terror lynchings in the U.S. between Reconstruction and World War II. The organization has placed markers at many sites and built a monument to the victims in Montgomery, Alabama.

The nation’s first anti-lynching legislation was introduced in 1918 amid national reaction to deaths of Mary and Hayes Turner and their neighbors in Georgia’s Brooks and Lowndes counties. It passed the House in 1922, but Southern senators filibustered it and another century would pass before lynching was made a federal hate crime in 2022.

“The same injustice that took her life was the same injustice that kept vandalizing it, year after year,” said Randy McClain, the Turners’ great-grandnephew. He grew up in the same rural area where the lynchings happened but did not know much about them or discover his family connection until he was an adult.

“Here it feels like a very safe space,” McClain said. “She’s now finally at rest, and her story can be told. And her family can feel some sense of vindication.”