Share and Follow

In Montgomery, Alabama, the legacy of Rosa Parks continues to shine brightly seven decades after she made history by refusing to surrender her seat on a bus. Recently unearthed photographs of this Civil Rights Movement icon have emerged, offering fresh insights into her enduring influence on American society.

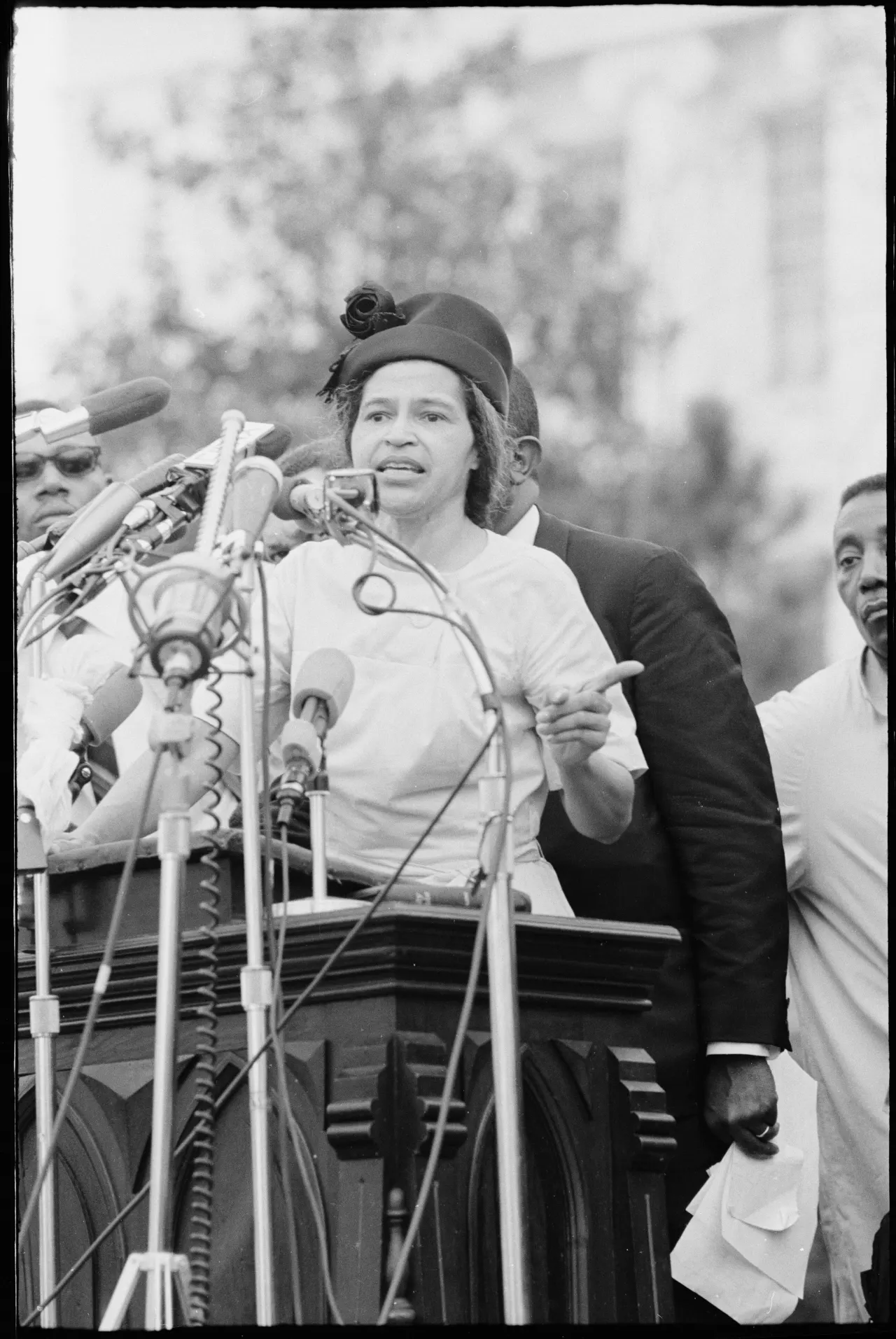

Taken by renowned Civil Rights photographer Matt Herron, these newly released images showcase Parks during the historic Selma to Montgomery march in 1965. This significant 54-mile journey, spanning five days, played a pivotal role in garnering support for the U.S. Voting Rights Act of 1965.

While history often highlights Parks’ pivotal act of defiance on December 1, 1955, which ignited the Montgomery Bus Boycott, her contributions to the Civil Rights Movement extend far beyond that moment. On Friday, participants of the boycott, along with descendants of its organizers, gathered to commemorate the 70th anniversary of this landmark 381-day protest in Alabama, which dismantled racial segregation on public transit.

The newly unveiled photographs, made public by the Rosa Parks Museum in Montgomery on Thursday, serve as a testament to Parks’ lifelong dedication to activism well beyond her famous bus protest. According to Donna Beisel, the museum’s director, these images provide a deeper understanding of Parks’ multifaceted role as both a person and an activist.

“These photos reveal the essence of Ms. Parks, capturing her spirit and activism,” Beisel stated.

Never printed before

There are plenty of other photos placing Parks among the other Civil Rights icons who attended the march, including some that were taken by Herron. But others were never printed or put on display in any of the photographer’s numerous exhibits and books throughout his lifetime.

Herron moved to Jackson, Mississippi, with his wife and two young kids in 1963 after Civil Rights activist Medgar Evers was assassinated. For the next two years, his photos captured some of the most notable people and events of that time. But in most of his photos, Herron’s lens was trained on masses of everyday people who empowered Civil Rights leaders to make change.

Herron’s wife, Jeannine Herron, 88, said that the photos going public this week were discovered from a contact sheet housed in a library at Stanford University.

The photos weren’t selected for print at the time because they were blurry or included people whose names weren’t as well known In Parks’ case, the new photos show her sitting among the crowd, looking away from the camera.

Now, Jeannine Herron is joining forces with historians and surviving Civil Rights activists in Alabama to reunite the work with the communities that they depict.

“It’s so important to get that information from history into local people’s understanding of what their families did,” Jeannine Herron said.

A joyous reunion

One of Herron’s most frequent subjects throughout the Selma to Montgomery march was a 20-year-old woman from Marion, Alabama, named Doris Wilson. Decades after he captured her as she endured the historic march, he still expressed his desire to reconnect with her.

“I would love to find where she is today,” Herron said in a 2014 interview among Civil Rights activists and journalists who witnessed that transformative period in the Deep South.

Herron died in 2020, before he had the chance to reconnect with Wilson. But on Thursday, Wilson joined other residents of Marion, a rural town in the Black Belt of Alabama. Milling around an auditorium in Lincoln Normal School, a college founded by nine formerly enslaved Black people after the Civil War, people looked at black and white photos that Herron took over the years, pointing out familiar faces or backdrops.

Some photos were familiar to the 80-year-old. But others, including ones where she was the subject, Wilson had never seen before.

One of the photos depicts Wilson getting treatment at a medical tent along the path of the march. Wilson had intense blisters on her feet from walking over 10 miles each day.

The doctor who was tending to her injuries, June Finer, also flew in from New York to reunite with Wilson for the first time since Finer gently cared for Wilson’s bare feet six decades earlier.

“Are you the one who rubbed my feet?” Wilson asked, as the two women laughed and embraced. Finer, 90, said she wasn’t even aware that people were taking photos — she was laser-focused on the safety of the marchers.

Later, Wilson reflected on how meaningful the reunion had been.

“I longed to see her,” Wilson said.

Robert E. Wilson, Wilson’s eldest son, said he had never seen the photos of his mother that were on display in the old school building where she went to school. He was a young child when she completed the march.

“I’m so stunned. She always said she was in the march, but I never knew she was strong like that,” the now 62-year-old who was raised in Marion said.

Years of searching

Cheryl Gardner Davis has faint recollections of the evening in 1965 when her family hosted the weary walkers on the third night of the march to Montgomery. She remembers hordes of strangers erecting tents on her family’s farm in the rural Lowndes County, Alabama. Just four years old at the time, she remembers how her mother and older sister had to mop up mud inside their hallway from people who had come in to use their landline phone.

It wasn’t until she was an adult that she fully understood the significance of her family’s sacrifice: Her mom’s job as a teacher was threatened, the family’s power was cut off and a neighbor menaced them with his rifle. For years, she scoured the internet and libraries for photo evidence of their hardship — or at least a picture of her family’s property at the time.

Among the hundreds of photos that made their way back to Alabama in the first week of December, were pictures of the campsite at Davis’ childhood home. Davis, who had never seen the photos before, said it was a vital way to bring light to the people who often are an afterthought in the recounting of that transformative historical period.

“It’s, in a sense, validation. This actually happened, and people were there,” Davis said.