Share and Follow

Elise Martin had just celebrated her 20th birthday. To fellow shoppers at a suburban mall in Canada, she appeared to be just another fashionable young woman on a quest for new outfits.

However, as she stood at the top of the escalator, an overwhelming fear took hold. This was her very first attempt at shopping alone.

“I stood there forever,” she recounted to the Daily Mail. “People kept passing by, puzzled as to why I was just standing there. But I simply couldn’t move forward.”

For over ten years, Elise’s existence had been under the strict control of her Saudi Arabian stepfather, alongside a regime that governed every facet of her life.

Engaged to her uncle at the tender age of six, subjected to the Kingdom’s harsh regulations that rob women of autonomy, and, as she claims, enduring mistreatment by her stepfather, Elise shares her remarkable journey in her memoir, Triumph: An American Girl’s Journey Out of Saudi Arabia.

Eventually, Elise took her first step onto that escalator. It was, she recalled, ‘joyous.’

She felt free – something she hadn’t really been since she was three years old, when her mother took her to Saudi Arabia and immersed her in an existence she describes as akin to ‘a real-life Handmaid’s Tale.’

Born in 1984 in San Diego, Elise’s American parents divorced when she was a baby and her mother decided to take Elise and her older brother overseas for a fresh start.

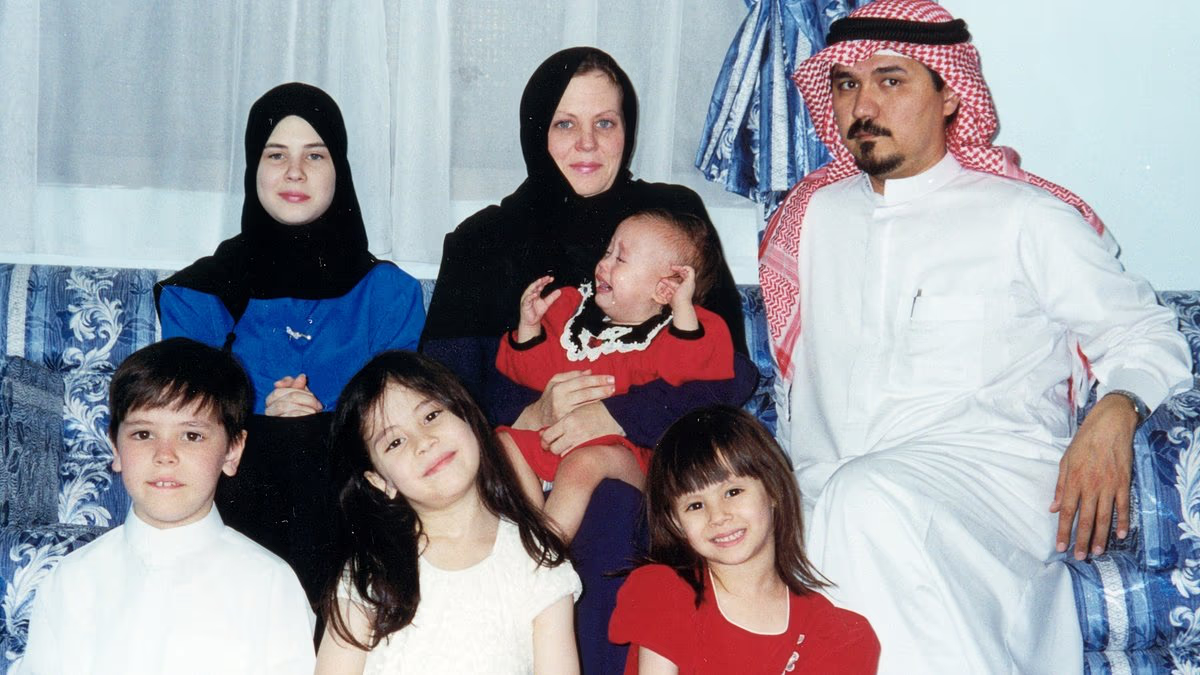

For more than a decade Elise’s life had been entirely dictated by the Saudi Arabian stepfather and the regime that handed him control over every aspect of her life

After Elise’s parents divorced, her mother decided to take Elise and her brother (left) overseas

She likened her experience in Saudi Arabia to ‘a real-life Handmaid’s Tale’

Elise’s maternal grandparents had moved to Saudi Arabia in the 1970s when her grandfather took a lucrative job as a technician at the King Faisal Specialist Hospital.

They lived, like many expats in the oil-rich Gulf state, behind the high walls of a luxurious diplomatic compound, insulated from the strict rules rooted in the fundamentalist Wahhabi interpretation of Islam that governed life for Saudis at the time. This was the home into which Elise and her family first moved.

‘I had the bedroom any girl would dream of,’ Elise said. ‘There was a painter who came and painted Minnie Mouse on my wall. It was pink and everything was rosy and beautiful.’

Her mother was happy in her job in the laboratory at the King Faisal hospital and Elise felt at home in the loving care of her grandparents.

But there were shadows of a far less ‘rosy’ life beyond the compound walls.

Elise remembers her grandfather taking her to buy a Barbie doll one day. The call to prayer sounded just as they arrived at the shop, summoning all Saudis to one of their five daily prayer times.

The shopkeeper quickly ushered them in as he closed the shutters.

The locals, Elise said, lived in fear of the stick-wielding ‘mutawa’ – religious morality police – who would chase men out of malls to pray, punish women for not wearing their all-encompassing black ‘abaya’ and enforce segregation of the sexes.

As they moved through the store’s darkened aisles, Elise’s grandfather whispered his request for the doll, which was contraband as it was considered obscene. ‘To a young girl, it was quite eerie,’ Elise said.

As expats, they enjoyed more freedoms than the locals. What she couldn’t have known was that she would soon be crossing over that divide.

Elise’s mother had fallen for a handsome Saudi man, who also worked at the hospital.

It took some time, but they navigated the rules governing marriage between a Saudi national and a foreigner and wed when Elise was six years old.

In a heartbeat, her life changed forever.

Elise’s mother (right) had fallen for a handsome Saudi man

Elise is pictured on the back of a camel, she guesses she was around four years old

‘There was a painter who came and painted Minnie Mouse on my wall. It was pink and everything was rosy and beautiful,’ she recalled

The family left the diplomatic compound and moved into an apartment in the Saudi capital of Riyadh.

Elise had been raised in the Mormon faith. Now, Christmas and Thanksgiving have been replaced by Muslim festivals and Saudi traditions.

She was instructed to cover her head with her Minnie Mouse scarf and started attending a Saudi school, where the textbooks referred to Americans as ‘infidels’ and claimed that the Holocaust never happened.

But Elise took it all in her stride. Intelligent and obliging, the little girl was happy to embrace this new culture: she started studying Arabic and enjoyed the sweets and money that came with festivals like Eid.

When her new step-grandmother offered her a gold ring and said Elise would one day marry her stepfather’s youngest brother, she was naively excited. ‘Little Elise thought it was a Cinderella fairy tale,’ she said.

Yet, according to Elise, her stepfather’s demeanor was gradually morphing from the warm and affectionate front he had first presented to something altogether more troubling.

There were flashes of cruelty. She claims that he became increasingly controlling and started to impose brutal punishments on the children. On one occasion, she alleges, he made Elise’s brother stand facing a wall all night for wetting the bed, telling Elise to watch him to make sure he obeyed.

Their life became isolated with fewer visits to Elise’s maternal grandparents.

When Elise was 11, the family moved to England for three years so that her stepfather could study for a PhD. But, for Elise, the move offered no relief from her ever more limited existence.

She went to an English school but had to come straight home at the end of each day, never spending time with classmates outside of school hours.

When Elise was 12 her mother pulled the children from school and took them back to Saudi Arabia. According to Elise, she spent most of the next six months locked in a room in her step-grandmother’s house.

When her stepfather returned from England, she claims that he became increasingly cruel, displaying an attitude towards her that, she says, was ‘facilitated’ by the culture of the country in which they lived.

‘There’s no fighting back. It’s not illegal to beat your daughter. Whatever I said wouldn’t matter.’

Elise (back row, left) with her mother (back row, center), her stepdad (back row, right) and some of her siblings

Elise (center right) and her brother (center left) with their cousins

Elise is pictured with her first husband, Ata

It was the late nineties in Saudi Arabia – a time during which every aspect of a woman’s life was governed by male guardianship laws. Women were not allowed to drive cars and needed a man’s permission for everything.

Adultery and fornication were crimes punishable by public flogging. To this day, the burden is on the woman to prove any allegations of sexual assault and victims who speak out run the risk of finding themselves punished for illegally fraternizing with a male.

In her teenage years, Elise found small ways to escape, such as putting on her roller-skates and making endless circles inside their small garage: ‘I was looking for something: I didn’t know at the time what it was, but I realize now that it was freedom.’

When she was 14, her betrothal to her uncle was abruptly called off and her family started shopping around for another potential husband. Candidates included a cousin and a 45-year-old man who already had a wife and two children.

Elise started to realize that marriage could be the only way to escape the family home. But she wanted to do it on her own terms.

She said: ‘My only recourse was to finally marry and get out and hope that I don’t go from the frying pan to the fire.’

During a computer studies course, she began secretly conversing on MSN Messenger with Ata, a young Syrian man in Canada. Soon they were exchanging love songs and plotting how they could be together.

A mutual friend set up a meeting of the families in Riyadh, and, to Elise’s surprise, her stepfather consented to the union.

Elise believes that her stepfather only allowed the marriage because Ata had a Canadian passport, which was seen as prestigious.

And so, Elise found herself at that escalator in the Canadian mall.

Today, she has a conflicted relationship with her past in Saudi Arabia. She is Muslim and there is, she said, much that she loves about the country in which she spent so many years.

But she said: ‘It’s like a cult. If you think Scientology, think Saudi Arabia, it’s basically the same.’

The marriage to Ata did not last and the couple divorced after three years.

For a long time, Elise struggled to assimilate into life in the West and she had several false starts when it came to her intimate relationships.

Now 41, she is happily married to husband number five and lives in New Orleans, Louisiana, where she devotes herself to advocating for the freedom of Saudi women.

She dismisses the modernization drive instigated by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in 2016, which means women can now drive and attend sporting events, as a superficial ‘rebranding’ of male guardianship rather than a fundamental change.

According to Elise, she still receives calls in the middle of the night from Saudi women who feel trapped and terrified, unable to escape as she did.

It’s why she is telling her story today. She said: ‘When you feel alone, you need to go arm in arm with someone and the book really is a way of saying, ‘You’re not alone.”