Share and Follow

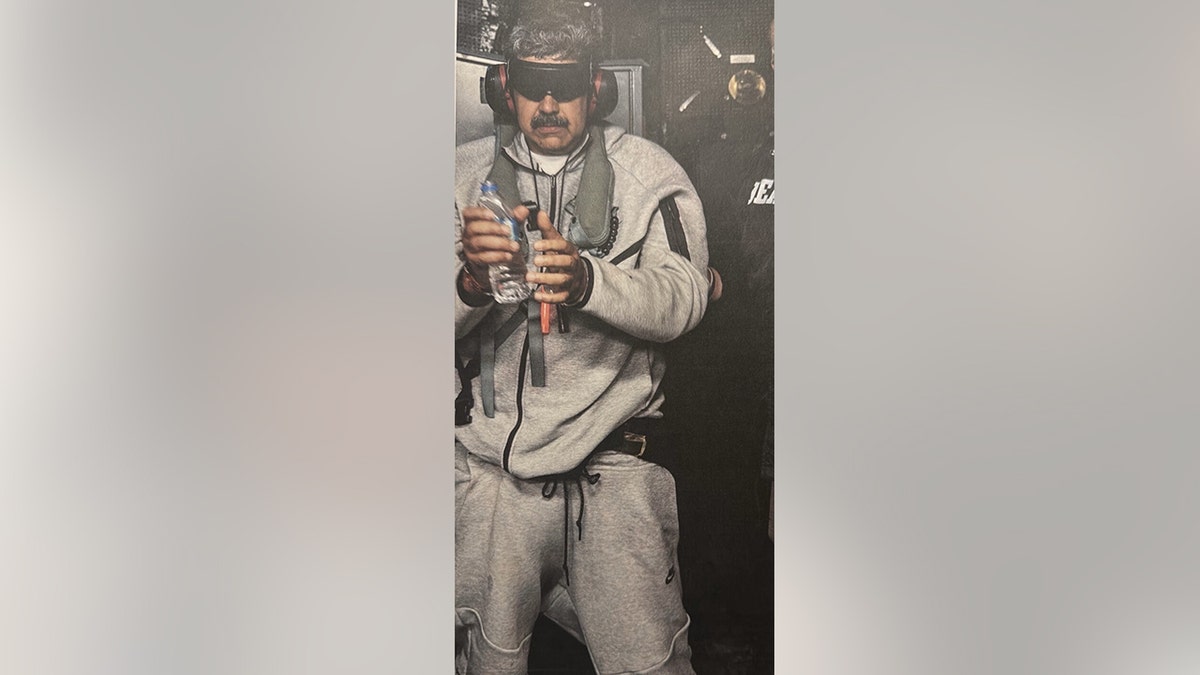

In a dramatic military operation early Saturday morning, U.S. forces successfully detained Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores. They are now facing federal charges related to alleged drug trafficking activities and accusations of running a dictatorial regime in Venezuela.

President Donald Trump had repeatedly called for Maduro to relinquish his leadership role, which many consider illegitimate. Trump accused Maduro of aiding drug cartels labeled as terrorist organizations by the United States.

U.S. officials revealed that the Department of Justice sought military intervention to capture Maduro following his 2020 indictment. This indictment also included charges against his wife, his son, two officials, and an alleged global gang leader for federal terrorism, drug, and weapons offenses.

Despite ongoing debates about the legality of these actions under the Trump administration, the U.S. has a history of similar operations against foreign leaders and suspected drug lords.

President Donald Trump posted a photo of the captured Nicolas Maduro on the USS Iwo Jima following the strikes in Venezuela on Saturday, January 3, 2026. (Truth Social/@realDonaldTrump)

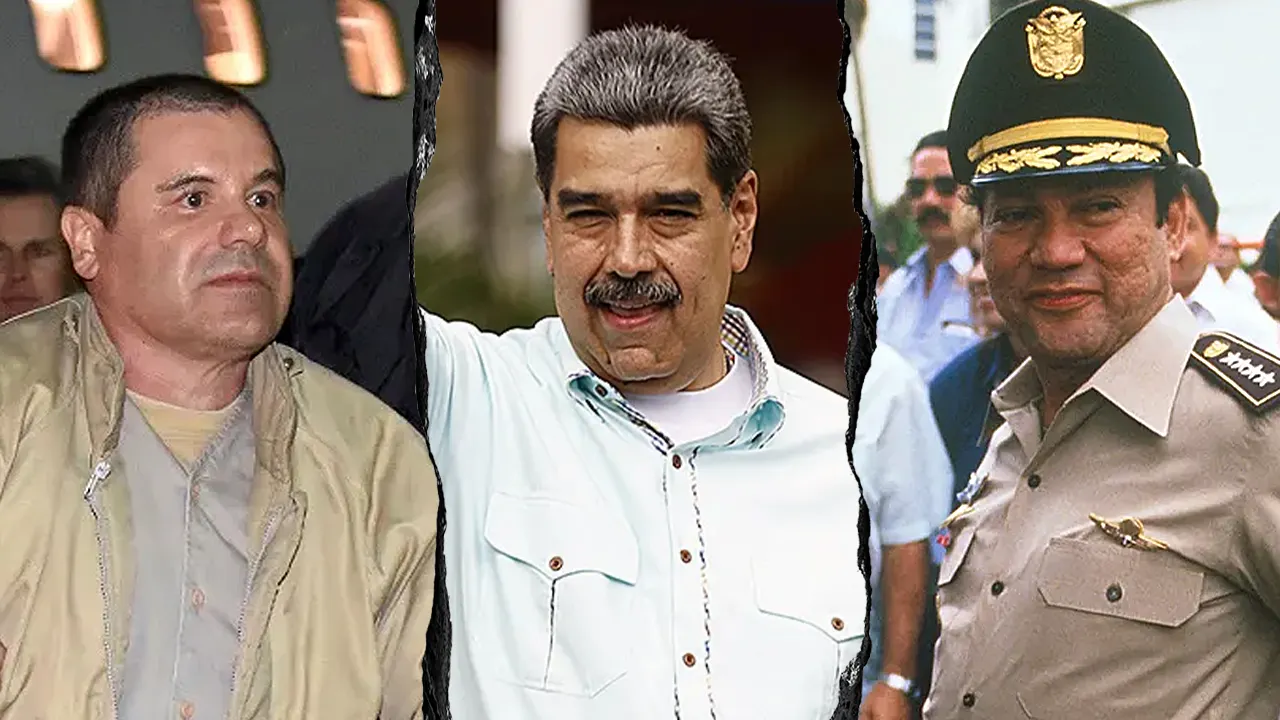

Here is a look at other instances in which U.S. officials took aim at some of the world’s most notorious leaders accused of being directly involved in some of the most prolific drug operations across the globe.

Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro addresses supporters during a rally marking the anniversary of the 19th-century Battle of Santa Ines in Caracas on Dec. 10, 2025. (Pedro Rances Mattey/Anadolu via Getty Images)

The conviction of Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega

In 1990, 36 years to the day of Maduro’s capture, the U.S. arrested Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega, under similar circumstances.

Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega at a ceremony commemorating the death of national hero Omar Torrijo in Panama City. (Bill Gentile/Corbis/Corbis via Getty Images)

Noriega initially rose to power in 1983, and was long viewed as an informant for the U.S. to provide information regarding drug trafficking in the region. Working as a paid CIA collaborator since the 1970s, Noriega allowed the U.S. to set up listening posts in Panama, while also allowing pro-American aid to funnel through Panama to El Salvador and Nicaragua.

However, under the nose of U.S. officials, Noriega formed “the hemisphere’s first narcokleptocracy,” a Senate subcommittee report said, calling him “the best example in recent U.S. foreign policy of how a foreign leader is able to manipulate the United States to the detriment of our own interests,” according to Reuters.

He reportedly worked alongside notorious drug cartel leader Pablo Escobar to funnel cocaine into the U.S., while also facilitating the movement of millions of dollars in drug cash through Panama’s banks, which led to him receiving large amounts of kickbacks.

Former Panamanian strongman Manuel Noriega, pictured in this Jan. 4, 1990, file photo. (Reuters/HO JDP)

One year before his arrest, a federal grand jury handed down a 12-count indictment against Noriega, effectively clearing the path for President George H. W. Bush to deploy thousands of U.S. troops to Panama in an operation titled, “Just Cause.” Noriega faced federal drug trafficking and money laundering charges.

As U.S. troops moved in on the country’s capital and military headquarters, Noriega sought refuge at the Vatican’s embassy while, according to a popular rumor, dressed as a woman.

Noriega was ultimately forced to surrender on Jan. 3, 1990, and was later sentenced to 40 years in a Florida prison. After 17 years behind bars, he was extradited to France and later Panama, where he died in 2017.

Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández’s arrest

In 2022, three months after leaving office, Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández was arrested at the request of U.S. officials at his home in Tegucigalpa on charges of working alongside drug traffickers to transport over 400 tons of cocaine into the U.S., according to The Associated Press.

Following his arrest, Hernández was extradited to the U.S. to stand trial for his alleged crimes.

Honduras President Juan Orlando Hernandez speaks during the opening ceremony of the U.N. Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, Scotland, on Nov. 1, 2021. (Andy Buchanan/AP)

U.S. officials alleged the disgraced leader had collaborated with drug cartels since 2004, accepting millions of dollars in bribes as his political career escalated from rural congressman to president of the National Congress to Honduras’ highest office.

During his trial in Manhattan federal court, Hernández testified that while drug money was paid to virtually all political parties in Honduras, he did not accept bribes while in office. He maintained that he was a victim of vengeful drug traffickers seeking retribution after he aided in their extradition to the U.S., while also working alongside three presidential administrations to limit drug imports into the country.

Hernández was subsequently convicted by a jury in March 2024, with a federal judge sentencing him to 45 years in a U.S. prison and issuing an $8 million fine.

Former Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernandez, second from right, is taken in handcuffs to a waiting aircraft as he is extradited to the United States, at an Air Force base in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, on April 21, 2022. (Elmer Martinez/AP)

However, after serving just 17 months of his sentence, Hernández was pardoned by Trump in late 2025.

“The people of Honduras really thought he was set up, and it was a terrible thing,” Trump said. “They basically said he was a drug dealer because he was the president of the country. And they said it was a Biden administration setup – and I looked at the facts and I agreed with them.”

After Trump announced Hernández’s pardon, Honduran Attorney General Johel Zelaya said in a post to social media that his office was looking into bringing charges against the former president, but did not specify what crimes officials were investigating.

Joaquin ‘El Chapo’ Guzman’s trial and guilty verdict

In 2017, Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, the notorious leader of Mexico’s “Sinaloa cartel,” was extradited to the U.S. to stand trial on drug trafficking and related crimes in several district courts throughout the country.

The notorious crime boss evaded capture on several occasions and escaped from Mexican prison twice, with federal prosecutors revealing Guzman used a variety of crafty tactics to smuggle tons of cocaine into the U.S. during the 1990s and early 2000s.

Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman when he was extradited from Mexico to the U.S. (AP)

Former cartel member Miguel Angel Martinez testified in federal court that the gang used trucks to carry 3,000 cans filled with cocaine over the U.S.-Mexico border, while estimating the vehicles carried 25 to 30 tons of cocaine worth $400 million to $500 million into the country each year, according to The Associated Press.

After the profits would arrive in Tijuana, Guzman would send his three private jets on a monthly basis to pick up the cash – with each plane carrying roughly $10 million back home.

Following his landmark federal trial in Brooklyn, Guzman was sentenced to life in prison – tacking on another prison sentence after an earlier guilty verdict on drug-trafficking charges resulted in a mandatory sentence of life without parole. A judge also ordered Guzman to pay $12.6 billion in ill-gotten proceeds stemming from his empire built on drug trafficking and murder.

Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman is escorted by soldiers during a presentation in Mexico City, Jan. 8, 2016. (Reuters/Tomas Bravo/File Photo)

A defiant Guzman used his final moments in the public spotlight to blast the judge for not granting him a new trial following unsubstantiated allegations of juror misconduct.

“My case was stained and you denied me a fair trial when the whole world was watching,” Guzman said through an interpreter.

Guzman is set to live out his days behind bars in the federal government’s Supermax prison, located in Florence, Colorado, where detainees are kept in solitary confinement for up to 23 hours a day.

“Since the government will send me to a jail where my name will not ever be heard again, I take this opportunity to say there was no justice here,” Guzman said at his sentencing.