Share and Follow

The city has recently experienced a troubling pattern, with three fatal shark encounters occurring within the past three years and two additional life-threatening incidents reported just in the last two days.

These alarming encounters seem to be increasing not only in New South Wales but also across state lines, prompting some Australians to feel apprehensive about venturing into the ocean.

Since the beginning of 2020, Australia has documented 23 fatal shark attacks across New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, and Western Australia.

To put this into perspective, the previous decade from 2010 to 2019 saw 22 fatal shark encounters, while each decade from 1960 to 2009 recorded fewer than 15. This suggests a concerning rise in fatal shark incidents.

The numbers appear to show a spike in fatal shark encounters.

But numbers don’t tell the whole story.

“Even though it sounds like a lot, it’s still a very, very low number,” Emeritus Professor of Marine Ecology at Macquarie University Robert Harcourt told 9news.com.au.

“It’s only a handful per year, and we have a lot of other factors that are changing much more rapidly.”

Climate change is making the weather and water temperatures warmer, so people are spending more time in the ocean.

That increases the likelihood of humans and sharks crossing paths.

Warmer waters are also bringing tropical inhabiting sharks like tiger and bull sharks further south for longer periods of time.

“White sharks are a cool water shark, but they are also relatively tolerant of warm water and they do go up into the north,” Harcourt said.

“So we’re getting a greater overlap of these three large predatory sharks.”

A string of La Niñas has caused major rainfall events across Australia’s east coast, which can trigger changes in fish behaviour.

Bait fish may cluster in areas like creek and river mouths, near rocks, or in the shallows after rainfall, which can attract sharks to swimming areas.

“When there’s a lot of food around, you’re going to get predators,” Harcourt said.

“We get clusters of bites when conditions are suited for them to be feeding in the same areas as people, and so that’s like a perfect storm.”

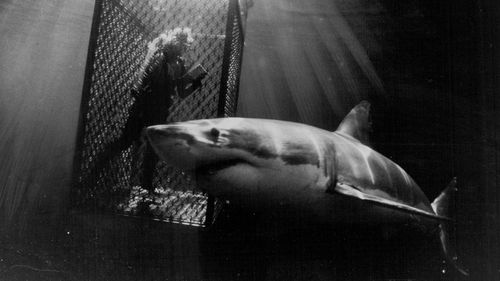

But most shark bites aren’t premeditated, malicious attacks, despite what films like Jaws would have people believe.

Conservationist and filmmaker Valerie Taylor AM, 90, spent the better part of her life in the water with sharks.

What she learned is that sharks don’t bite humans because they want to kill them.

”We are not their natural prey,” she told 9news.com.au.

“When you get bitten, it’s because they lack hands, they can’t feel you, so they’re feeling with their teeth.”

(Taylor also filmed the real great white shark sequences for Jaws with her late husband Ron Taylor. Both regretted that the film inspired such hatred and fear of sharks.)

Taylor was bitten multiple times, including once on the chin, but never blamed the sharks involved.

She accepted that she was taking a risk every time she entered their domain.

“If you go into the jungle, there’s always the possibility of meeting a tiger. If you go into desert bushland, you might meet a snake,” she said.

“It’s always been that way, and it’s not going to change.”

Just as there’s a risk of drowning when you swim in the ocean, there’s also the risk of encountering a shark.

Every fatal encounter sparks calls for shark culls, or for the fish responsible to be hunted down and killed.

“I don’t know why they say, ‘Let’s kill all the sharks,’” she said.

“You’re never going to be able to do that, and they are very important in the ocean.”

Wiping out sharks, or even just dramatically reducing numbers, would devastate Australia’s already changing marine ecosystems.

Instead, the focus should be on education and prevention.

It’s impossible to prevent all shark bites in Australian waters but existing deterrents and new technologies will continue to reduce the risk of fatalities.

“So long as there are large predatory fish in the ocean – and we need them, they’re very, very important components of the ecosystem – there will be a risk,” Harcourt said.

“But there are lots of ways in which things are improving already.”

Queensland is using drones to monitor beaches.

The Western Australian Government offers residents $200 rebates for personal shark deterrent devices.

Australia’s Integrated Marine Observing System (IMOS) collects data from tagged sharks which can be used to develop models that can help predict the risk of shark encounters in our waters.

Australians also have a better understanding of how to respond to shark bites now, which can be enough to save lives.

“That poor boy who was bitten [on Sunday], he would have almost certainly died in years gone past,” Harcourt said.

“But because of his incredibly brave friends, and the proximity of the police boat, and the fact that they put tourniquets on straight away, and they got him to the ambulance really quickly, he got the best possible chance [to survive].”

To reduce the risk of shark encounters, avoid being in the water at dawn and dusk, keep clear of schools of bait fish, and monitor shark warnings.

If in doubt, stick to public pools.