Share and Follow

The recent UN Human Rights Council review has brought significant scrutiny to Australia, with numerous countries urging the nation to adopt a national human rights act that could potentially address hate speech. The session, held overnight, saw various nations voicing concerns about Australia’s human rights practices.

A central focus of the criticism was Australia’s treatment of its Indigenous population, particularly the troubling overrepresentation of Indigenous children in the justice system. There is a growing international push for Australia to increase the age of criminal responsibility, a point that resonated strongly with many attending countries.

In response to the review, Hugh de Kretser, President of the Australian Human Rights Commission, emphasized that as a “wealthy, stable democracy,” Australia should be at the forefront of protecting human rights. He acknowledged that the review has highlighted several areas where the nation “must do better.”

De Kretser noted that the most significant concerns revolved around the rights of First Peoples, especially issues related to inequality, racial discrimination, and justice outcomes. The call to raise the age of criminal responsibility was a prominent theme, with many countries advocating for this change.

“In particular many countries called on Australia to raise the age of criminal responsibility.

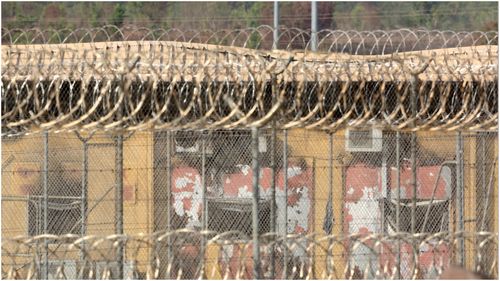

“In most Australian jurisdictions, children as young as 10 can be arrested, prosecuted and jailed. This is inhumane and remains out of step with international human rights standards.

“First Peoples are hit hardest by these unjust laws. The international community is calling us out on this.”

Kathryn Haigh, the first assistant secretary in the Attorney-General’s Department international cooperation and human rights division, said Australian states and territories were primarily responsible for handling their own criminal justice systems but said there’d been improvements since 2021.

“This has included investing in fit for purpose prisons, rehabilitation and reintegration programmes, diversionary programmes and non-custodial options to reduce recidivism and prison populations, including programmes to reduce the over-representation of First Nations peoples,” she said.

“Australia recognises that it must do more to address the over-representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the criminal justice system”.

She gave five commitments to the review from the Australian government.

She said it would review the Disability Discrimination Act in accordance with royal commission recommendations, increase appropriate affordable housing for Indigenous people, deliver the Our Ways – Strong Ways – Our Voices plan to end domestic and family violence, legislating the National Commission and National Commissioner for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young people, and to increase investment into dementia.

National Indigenous Australians Agency CEO Julie-Ann Guivarra acknowledged more progress was needed to achieve lasting change for First Nations people but insisted the country was acting with “urgency and resolve”.

“[Australia’s] is a rich, proud and deeply remarkable story, a story of hope, achievement and survival against the odds,” she said.

“Our stories are intertwined, but as the Closing the Gap Report routinely lays bare, there are still too many areas in which we are not together.

“We have made progress, but real change takes continued effort to listen to First Nations voices, to act and to deliver practical outcomes that improves lives.

“Our goal is clear, to close the gap and ensure equal life outcomes for all Australians.”

The report is set to be adopted on Friday afternoon (early Saturday AEDT).