Share and Follow

In a world where glaciers are increasingly retreating, scientists have stumbled upon a perplexing phenomenon: around 3,100 glaciers are experiencing a ‘surge.’ While this might initially seem like a positive development, experts caution that it poses its own set of serious challenges.

Rather than offering a reprieve, these surging glaciers can be more problematic than their retreating counterparts. A surge occurs when a glacier suddenly propels substantial amounts of ice downhill, an accumulation built over many years. Upon reaching lower altitudes, this ice rapidly melts due to the warmer temperatures.

In certain regions, glaciers prone to surging contribute significantly to ice loss, with some even described as ‘surging themselves to death.’ This alarming behavior not only spells trouble for the glaciers but also heralds even graver implications for nearby communities.

For those living in proximity to these natural ice giants, the implications are worrying. The sudden influx of water from melting ice could lead to floods and other environmental hazards, raising urgent concerns for the safety and sustainability of these communities.

While this is bad news for the glaciers themselves, the outlook is even worse for the people who live beside them.

Unlike most glaciers, which move gradually forward, surging glaciers shift in short bursts of rapid movement lasting a few years, followed by decades-long periods of quiet.

Lead author Dr Harold Lovell, a glaciologist from the University of Portsmouth, says: ‘They save up ice like a savings account and then spend it all very quickly like a Black Friday event.

‘But while they only represent one per cent of all glaciers worldwide, they affect just under one–fifth of global glacier area, and their behaviour can result in serious and sometimes catastrophic natural disasters that affect thousands of people.’

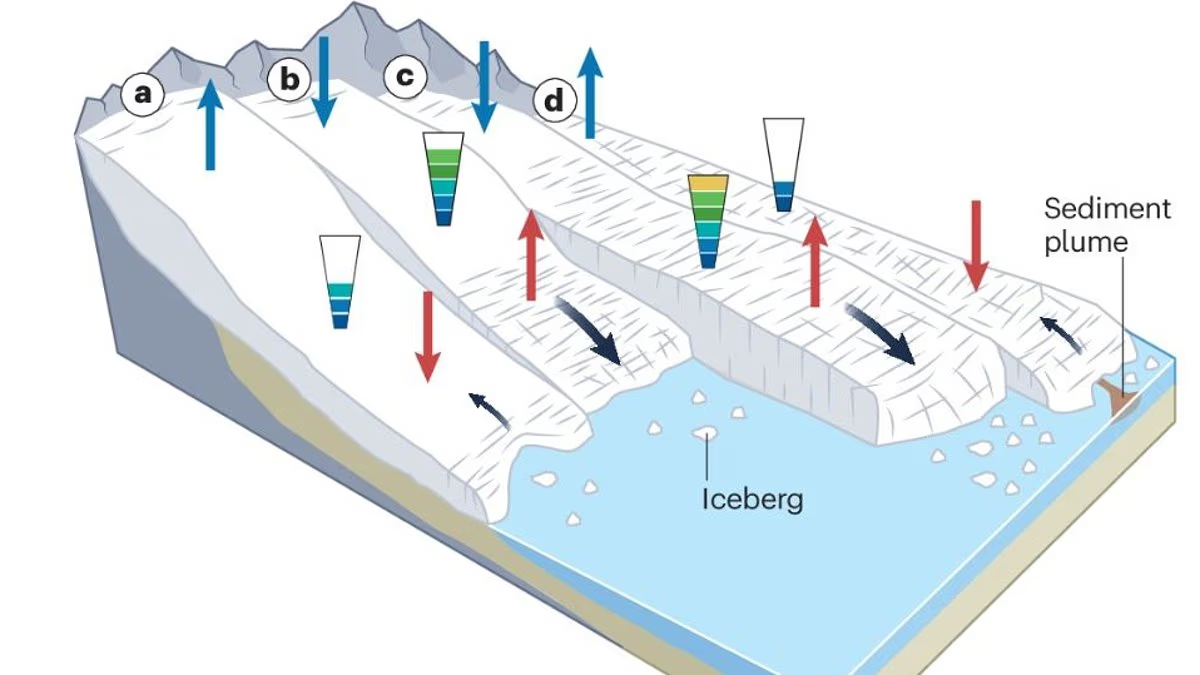

Scientists have discovered 3,100 glaciers that are not retreating but surging (illustrated), as they warn that this could be even more ‘troubling’

Scientists aren’t entirely sure what triggers surges, but research suggests they are probably related to conditions in the glacier’s underside, where ice meets the ground.

These glaciers store massive reserves of ice until heavy rainfall or hot weather trigger a buildup of water beneath the ice, reducing friction and allowing the glacier to slide downhill.

Although it might temporarily look like the glacier is advancing, the results are often catastrophic for the glacier.

Dr Lovell told the Daily Mail: ‘When glaciers surge, they very quickly spend all the ice they have built up over a long period of time. This ice then melts away in warmer temperatures at lower elevations, leaving the glacier very vulnerable.

‘There are examples of glaciers “surging themselves to death” – losing so much ice during a surge that they cannot recover in the current warmer climate.’

Surging glaciers are also highly concentrated in just a few dense clusters in the Arctic, High Mountain Asia, and the Andes, where there is the right balance of temperature and precipitation.

The problem is that these surges result in huge changes to the environment around the glacier, which can be devastating for nearby settlements.

Glacier surging creates serious hazards for people living near the ice, as the advance threatens to swallow homes, trigger flooding, create landslides, and fill waterways with dangerous icerbergs

The threat posed by the world’s surge–prone glaciers (illustrated) is made worse by the fact that these events are so unpredictable

Glacier advances can overrun roads, farmland, and even buildings, as well as blocking rivers, creating lakes that can release dangerous floods.

During a surge, meltwater that has built up beneath the glacier can suddenly be released in the form of a devastating flash flood.

The rapid movement forward also makes the glacier less stable, creating a network of widespread crevasses that can be perilous for anyone travelling over the ice.

In extreme cases, the glacier may begin to break up, releasing hazardous icebergs or suddenly detaching in a large ice and rock avalanche.

In their paper, published in Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, the researchers identified the 81 glaciers that pose the greatest danger when they surge.

Most of these are in the Karakoram Mountains, which span China, India, and Pakistan, where populated valleys and critical infrastructure sit directly below surging glaciers such as the Shisper and Kyagar.

However, they can also be found all over the world, with serious threats posed by the Tweedsmuir Glacier in Alaska-Yukon and the Kolka Glacier in the Caucasus.

This risk is made worse by the fact that surges are very hard to predict, and climate change is only making them less reliable.

Of the 81 most dangerous glaciers in the world, most are in the Karakoram mountain range, where inhabited valleys sit directly below surging glaciers such as the Shisper glacier (pictured)

In some areas, glaciers are now so thin that they don’t have the ice to surge, but others are now surging more than ever.

Dr Lovell says: ‘We have been able to piece together the growing body of evidence that shows how climate change is affecting glacier surges, including where and how often they happen.

‘This includes instances of extreme weather such as heavy rainfall events or very warm summers, triggering earlier than expected surges, suggesting an increasing unpredictability in their behaviour.’

Surges might stop altogether in places like Iceland, where glaciers are shrinking rapidly and struggling to build up ice.

But they could become more frequent in parts of High Mountain Asia and in the Canadian and Russian Arctic due to warmer temperatures and increased meltwater.

The researchers even suggest that surges could be seen in the Antarctic Peninsula, where surging glaciers have never been seen before.

Co–author Professor Gwenn Glowers, of Simon Fraser University in Canada, says: ‘Just as we’re starting to develop a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms behind glacier surges, climate change is rewriting the rules.

‘Extreme weather events that might have been rare even 50 years ago could become triggers for unexpected surges. Given that surges cause hazards in some settings, this makes protecting vulnerable communities much more difficult.’