Share and Follow

The Strait of Messina Bridge will be “the biggest infrastructure project in the West,” Transport Minister Matteo Salvini told a news conference in Rome, after an interministerial committee with oversight of strategic public investments approved the project.

Salvini cited studies showing the project will create 120,000 jobs a year and accelerate growth in economically lagging southern Italy, as billions more in investments are made in roads and other infrastructure projects accompanying the bridge.

Preliminary work could begin between late September and early October, once Italy’s court of audit signs off, with construction expected to start next year.

Despite bureaucratic delays, the bridge is expected to be completed between 2032-2033, Salvini said.

The Strait of Messina Bridge has been approved and cancelled multiple times since the Italian government first solicited proposals in 1969.

Premier Giorgia Meloni’s administration revived the project in 2023, and this marks the furthest stage the ambitious project— first envisioned by the Romans — has ever reached.

“From a technical standpoint, it’s an absolutely fascinating engineering project,” Salvini said.

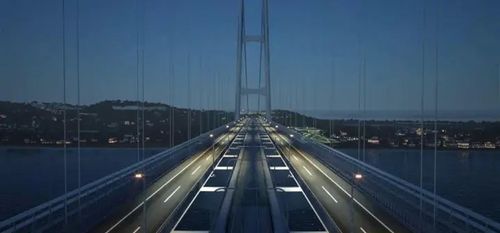

The Strait of Messina Bridge would measure nearly 3.7 kilometres, with the suspended span reaching 3.3 kilometres, surpassing Turkey’s Canakkale Bridge, currently the longest, by 1277 metres.

With three car lanes in each direction flanked by a double-track railway, the bridge would have the capacity to carry 6000 cars an hour and 200 trains a day — reducing the time to cross the strait by ferry from up to 100 minutes to 10 minutes by car. Trains will also save transit time, Salvini said.

The project could provide a boost to Italy’s commitment to raise defense spending to 5 per cent of GDP targeted by NATO, as the government has indicated it would classify the bridge as defence-related, helping it to meet a 1.5 per cent security component.

Italy argues that the bridge would form a strategic corridor for rapid troop movements and equipment deployment to NATO’s southern flanks, qualifying it as a “security-enhancing infrastructure.”

Salvini confirmed the intention to classify the project as dual use, but said that was up to Italy’s defence and economic ministers.

A group of more than 600 professors and researchers signed a letter earlier this summer opposing the military classification, noting that such a move would require additional assessments to see if it could withstand military use.

Opponents also say the designation would potentially make the bridge a target.

Environmental groups have lodged complaints with the EU, citing concerns that the project will impact migratory birds, noting that environmental studies had not demonstrated that the project is a public imperative and that any environmental damage would be offset.

The original government decree reactivating the bridge project included language giving the Interior Ministry control over anti-mafia measures.

But Italy’s president insisted that the project remain subject to anti-mafia legislation that applies to all large-scale infrastructure projects in Italy out of concerns that the ad-hoc arrangement would weaken controls.

Salvini pledged that keeping organised crime out of the project was top priority, saying it would adhere to the same protocols used for the Expo 2015 World’s Fair and the upcoming Milan-Cortina 2026 Winter Olympic Games.

“We need to pay attention so that the entire supply chain is impermeable to bad actors,” he said.

The project has been awarded to a consortium led by WeBuild, an Italian infrastructure group that initially won the bid to build the bridge in 2006 before it was later cancelled.

WeBuild constructed the Canakkale Bridge using the engineering model originally devised for the Messina bridge. It includes a wing profile and a deck shape that resembles a fighter jet fuselage with openings to allow wind to pass through the structure, according to WeBuild.

Addressing concerns about building the bridge over the Messina fault, which triggered a deadly quake in 1908, WeBuild has emphasised that suspension bridges are structurally less vulnerable to seismic forces.

It noted that such bridges have been built in seismically active areas, including Japan. Turkey and California.

WeBuild CEO Pietro Salini said in a statement that the Strait of Messina Bridge “will be transformative for the whole country.”