Share and Follow

Why is this agreement causing so much debate, and what prompted a state government to kick off a marketing campaign about it? Here’s what you need to know.

Let’s start with some background information to set the stage.

Each year, the federal government allocates billions of dollars to states and territories across the country. Despite having substantial programs to manage, such as public hospitals and schools, these regions face limitations in their ability to generate revenue independently.

A significant portion of this federal funding—approximately half—comes directly from the Goods and Services Tax (GST). The disbursement of these funds is determined through a specific formula, which ultimately results in a figure known as the GST relativity.

This relativity score plays a crucial role in the distribution of funds. A score of 1 signals an average need for financial support, while a score higher than 1 suggests a greater need, and a lower score indicates a lesser need.

The idea is to make sure that each jurisdiction can provide the same level of services to its residents as any other can, taking into account how much it would cost for a state or territory government to service its population, but also the ability of that government to raise revenue.

So the Northern Territory, for example, has always had the highest GST relativity because of the cost of providing services to its remote Indigenous community, coupled with its small economy.

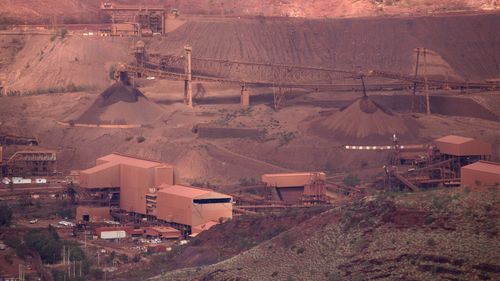

For the last decade and a half, WA has been the major outlier at the other end of the scale, with the revenue from mining royalties making it the richest state on a per-person basis – and leaving it with comparatively little need for GST payments from the federal government.

However, in 2018, the Turnbull government and then-treasurer Scott Morrison introduced a new model for distributing GST, which set a floor for payments: no state’s relativity could fall below 0.75, meaning each state or territory receives no less than 75 cents for every dollar of GST it raises.

Why is that so controversial?

Two reasons: it’s very expensive, and it clearly benefits Western Australia above all other states and territories.

Without the deal, WA’s GST relativity for 2025-26 would have been about 0.18 – well short of the 0.75 it actually received because of the new floor.

In real terms, that’s an extra $6 billion a year for a state budget that is in a better shape than any other – money that otherwise would have gone to the other states.

So, to keep them happy, the 2018 deal also included top-up payments to ensure no one was left worse off under the revamped system.

The payments haven’t managed to keep everyone content – NSW Treasurer Daniel Mookhey, for example, has regularly cried foul – and they’ve also proven to be far more expensive than first thought.

The original forecast put the cost of the payments at $8.95 billion over 10 years.

In reality, they cost more than that in the past two years alone, and the overall price has surged past $50 billion – all at a time when the federal budget is deep in the red and the government is under pressure to rein in spending.

All this happened years ago. Why is WA lobbying about the changes now?

Because the deal is so popular in WA – a crucial battleground in recent elections – both sides of politics have offered nothing but support for it.

However, the Productivity Commission is currently reviewing the GST arrangements, and the public has been invited to make submissions.

“It’s about making sure these arrangements are delivering the best value for states and territories, as well as hardworking Australian taxpayers,” Treasurer Jim Chalmers said when the report was announced in September.

The same day, WA Treasurer Rita Saffioti announced a so-called “fairness fighter” to lead the state’s response to the review, and this week Premier Roger Cook unveiled the advertising blitz to promote the distribution deal.

His campaign argues that the state’s share of GST is being used to create infrastructure that is crucial for the entire nation.

“We utilise that revenue to ensure that we can develop the economic infrastructure, create the frameworks and the regulation to create the industry, which ultimately pays significant resources to the Commonwealth and other states,” he told ABC radio yesterday.

But economists are unlikely to be swayed by those claims.

Public policy expert Robert Breunig has previously called the deal a “disaster”, while fellow respected economist Saul Eslake has been even more scathing, calling it “the worst public policy decision of the 21st century thus far” and WA’s recent arguments “vacuous” and “without foundation whatsoever”.

The Productivity Commission is due to deliver an interim report to the government next August before making its final recommendations by the end of 2026.