It was meant to make healthy choices simple, but nutrition experts say the Health Star Rating system is falling short.

According to its critics, the front-of-pack labelling system for food and drink lacks consistency across products, uses an algorithm that overlooks ultra-processed foods and artificial sweeteners, and — because displaying a rating is not mandatory — is more likely to be applied to products that score higher as a promotional tactic.

After a five-year process in the wake of a 2019 review, Friday marks the final deadline for food and beverage manufacturers to voluntarily apply the rating to 70 per cent of relevant products.

The government has pledged to look into making the system mandatory if the intended goals are not achieved, and it seems that this scenario is now unfolding.

Research by the Sydney-based The George Institute for Global Health found that uptake across the industry in 2025 was just 37 per cent.

Uptake has stagnated in recent years. Last November, only 35 per cent of intended products in Australia displayed a star rating, according to government data, up just a fraction from 32 per cent the year before.

Alexandra Jones, head of food governance at The George Institute, said the government targets were “extremely generous, yet the multibillion-dollar packaged food industry has not even come anywhere close to meeting them”.

“This is an abject failure by the industry that suggests a blatant disregard for Australian consumers who buy their products.”

Julian Rait, vice president of the Australian Medical Association, told SBS News mandating the system is “the only way to ensure that there will be a benefit to consumers and not just industry from the Health Star Ratings”.

“It appears that food manufacturers are being quite selective about where they apply Health Star Ratings,” an official commented. “They often highlight their healthier products with the ratings, using them as a marketing advantage, while avoiding their use on less healthy items.”

The Health Star Rating system evaluates the nutritional quality of packaged foods and beverages, assigning a score ranging from 0.5 to 5 stars.

The government initiative was introduced in Australia and New Zealand in 2014 in consultation with industry and public health stakeholders.

Source: SBS News

Using an online calculator, manufacturers plug in four key “negative” nutrients which lower the score of an item: kilojoules, saturated fat, sugars and sodium.

They can then add four “positive” inputs that increase the rating. These are:

– Fibre

– Protein

– Fruit, vegetable, nuts and legume content (FVNL)

– Concentrated fruit or vegetable ingredients such as tomato paste

It’s intended to compare similar products — so cheese against other cheese products, but not cheese against muesli bars.

Sarah Dickie, a research fellow in the Department of Nutrition, Dietetics and Food at Monash University, told SBS News that allowing positive components to negate negative ones is not an ideal system.

“This idea of being able to add enough good ingredients in to balance that out, it doesn’t really work. It’s still a junk food.”

Low-rated products less likely to display a rating

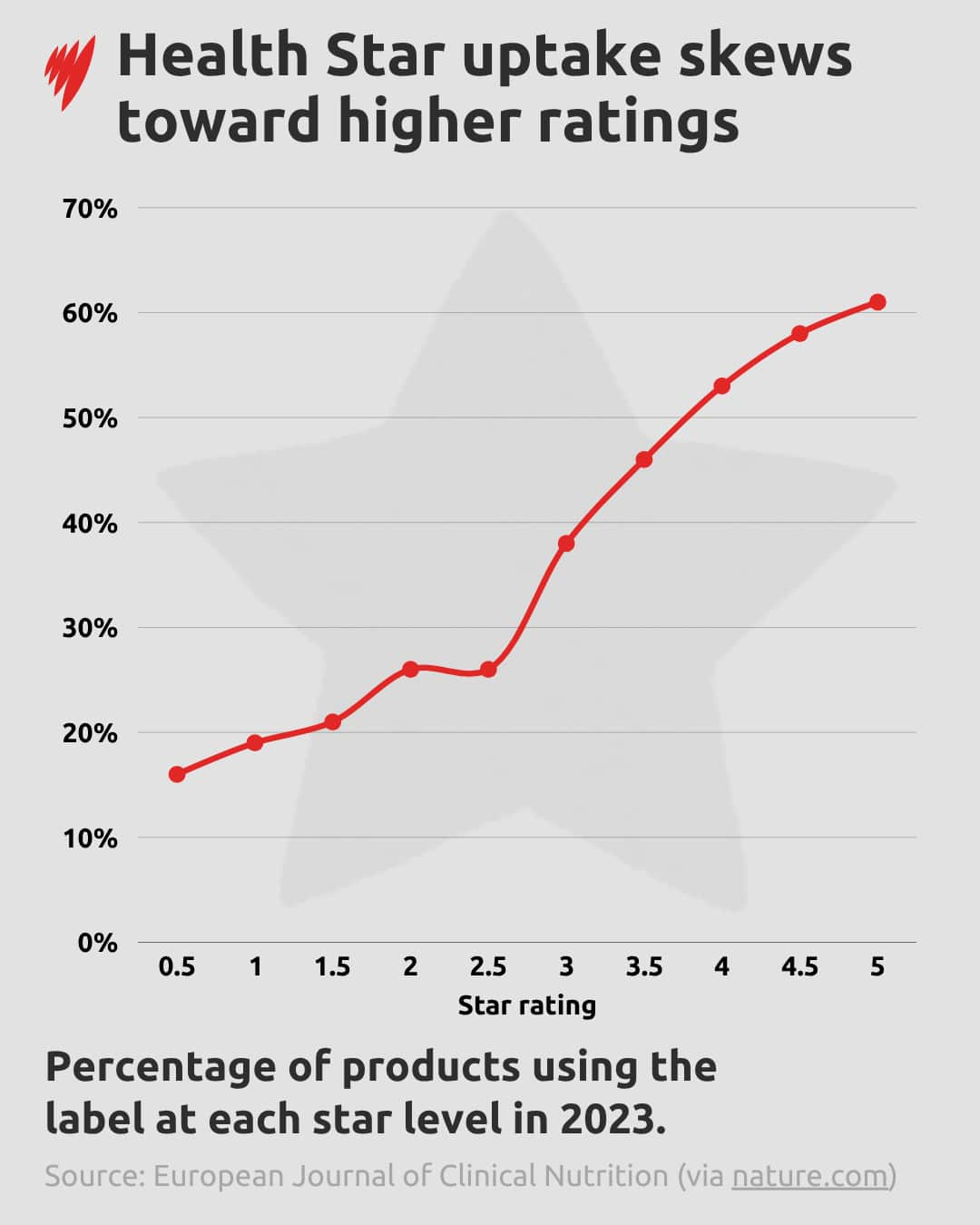

Research from The George Institute across more than 21,000 products last year found that 61 per cent of five-star items displayed their rating.

Just 16 per cent of products that would receive half a star were labelled, and only 24 per cent of products that scored three stars or lower showed a rating.

Jones, of The George Institute, said in August the lack of consistency makes it difficult for consumers to compare items.

She called for a “clear and expedient timeline” to mandate ratings in addition to regular, independent reviews of the algorithm underlying the system.

Processing not factored in

Ultra-processed foods (UPFs) are made with few whole foods, created using industrial techniques, modified substances and various additives. They include products such as chips, carbonated or artificially-sweetened drinks, lollies, certain cereals and energy bars.

Processing is not captured by the Health Star Rating algorithm, despite growing evidence linking UPFs to numerous harmful health outcomes including heart disease and diabetes.

“You’re getting these ultra-processed foods that can go through the algorithm and say they’re really healthy,” said Dickie, whose research has looked specifically at the Health Star Rating system.

Artificial sweeteners are also not accounted for by the system, meaning zero-sugar soft drinks and cordials can rate up to 3.5 stars.

While some positive adjustments were made to the rating system after a previous review, Dickie said there are still some “fundamental flaws” in the algorithm.

“You can go around the supermarket and find things that are heavily processed, you know, like Up & Go, or even artificially-sweetened soft drink — 3.5,” she said.

“That does not make any sense, right?” she added. “There’s no nutritional value [in artificially-sweetened soft drink].”

Artificial sweeteners have been linked to gut issues, she said, and can promote taste preferences for sweetened food and drinks.

“If you’re having those from a young age, you’re developing a taste for sweetness, which is not good for your dietary habits.”

Up & Go liquid breakfast products, which contain fibre and protein, rate between 4.5 to 5 stars. Various brands of packaged chips have ratings of up to 3.5 stars. Milo snack bars have ratings of 4 stars while other snack products like LCMs choc-chip display a 1-star label.

Consumers want more transparency, surveys suggest

A 2024 VicHealth survey of 1,100 Australians found that nutrition information was the second most important factor influencing food purchases after price, yet many respondents said they didn’t trust food labels to be transparent.

Similarly, a 2023 Cancer Council survey found 82 per cent of Australian adults believe Health Star Ratings should be included on all packaged foods.

About two-thirds said making the system mandatory would make it more useful, and 65 per cent said it would help simplify their purchasing decisions.

Should a flawed system be mandated?

Experts agree that a compulsory system is crucial, but differ on where to go from here.

Magriet Raxworthy, CEO of Dieticians Australia, said the peak body supports making the current system mandatory, but said “there’s still opportunity for improvements” in future.

“I do believe it is going to set us on a motion in the right direction, and certainly enabling the Australian public to make more informed choices,” she told SBS News.

She suggested that outlier products with inaccurate ratings make up only a small fraction of the picture, but said the large majority “do provide the right information”. She called, however, for better messaging to the public on how to appropriately read the ratings.

“We know that people are comparing Health Star Ratings of products outside of groupings, and that means you’re also not utilising the system correctly,” she said.

Dickie, who is also an executive member of the advocacy group Healthy Food Systems Australia, said she doesn’t believe the current model is fit for purpose.

That group would not want the system mandated in its current form.

“Our preference would be to change it to a warning-based system,” she said.

Food ministers meeting early next year

A Department of Health spokesperson told SBS News that food ministers will meet early next year to review reporting on uptake and receive updates from Food Standards Australia New Zealand — the agency that develops food standards and policies for both countries — on preparatory work it has undertaken on potentially mandating the system.

“Based on this update, food ministers will further consider whether to mandate the HSR system,” the spokesperson said.

If ministers decide to mandate the system, it could still take several years before consumers see the effects on the shelves.

The spokesperson noted the existing system was designed to align with the Australian Dietary Guidelines, which don’t reference processing level.

Those guidelines are under review, and once an updated version is released, “consideration will be given to whether the HSR system remains aligned”.

“The HSR does not replace nutrition know-how. Unlike dietary guidelines, it doesn’t tell you what types of food to eat or in what quantities. Just because a product has a 5 star rating does not mean you should eat it every day or in large amounts,” the spokesperson said.

“Health Stars help consumers to quickly and easily compare similar products. It won’t help you to choose between bacon and breakfast cereal. But if you’ve decided to buy breakfast cereal then it will help you to choose a healthier option.”

The Australian Food and Grocery Council, the peak industry association for the food, beverage and grocery supply industry, told SBS News it “supports the Health Star Rating system as a tool to help Australians make informed food choices”.

“For many companies, particularly small manufacturers, introducing or revising packaging involves considerable time, cost and logistical complexity,” a spokesperson said.

“Any shift of the HSR to a mandatory measure would require adequate timeframes and support to ensure long-term planning and avoid unnecessary waste or disruption to production.”

What could a different approach look like?

Dickie pointed out that the existing system is positively skewed — by design, every product technically has a positive star rating above 0.5, even those that rank most poorly.

Research on front-of-pack labelling suggests that a warning system or negatively-skewed system is more effective.

“Something that actually puts a warning label on junk foods and points out the products that we shouldn’t be eating is going to be more effective than this kind of ranking-based system that is positive,” she said.