Thanh Nguyen was just three years old when the Vietnam War began.

His childhood in Saigon — the former capital of South Vietnam — was marred by fear and uncertainty.

By 19, he was thrust into battle.

Now, half a century after the Fall of Saigon, Nguyen is 73, but his memories remain as vivid as that historic day in April 1975.

While for some, it marked the end of a decades-long war, for Nguyen and millions of South Vietnamese veterans like him, it was far from over.

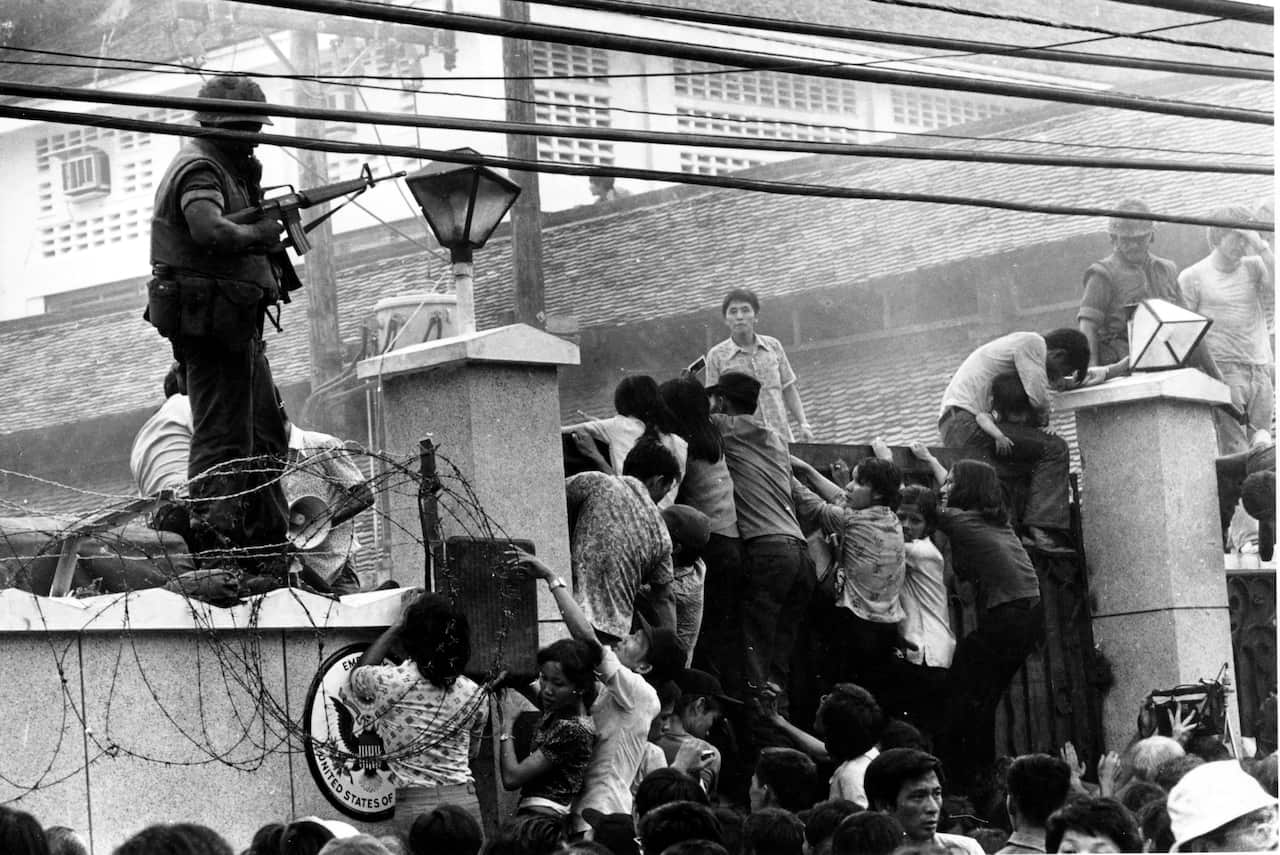

Vietnamese civilians and Americans rush toward a US Marine helicopter on 29 April 1975, during the chaotic evacuation of Saigon, as the city fell to North Vietnamese forces. Source: AP / .

Haunted by a war that never ended

When the last helicopter packed with evacuees lifted off the rooftop of the US Embassy in Saigon on 30 April 1975, chaos broke out.

It was a powerful symbol of America’s final withdrawal as the communist North Vietnamese forces closed in and a moment of desperation for thousands of South Vietnamese civilians and allies, many of whom clung to the hope of evacuation.

Nguyen’s family were among those who chose to stay behind.

“Yes, lots of people tried to escape at the time, but we stayed,” he tells SBS News.

“[Because] I can ask the contrasting question … where could we go? Everywhere was the same.”

Thanh Nguyen as a young man in Bien Hoa, Vietnam, before his enlistment. Source: Supplied / Thanh Nguyen

Nguyen was 23 at the time Saigon fell, bringing his four years of service to an end. It left him with mixed feelings.

“I wasn’t interested in joining the army,” he says.

But then I thought — if I do go, that is how I can contribute to my country.

His family had lived beside the Bien Hoa air base, a major target of the Viet Cong — the communist-led South Vietnamese military front backed by North Vietnam.

As a boy, Nguyen would climb onto the rooftop to watch helicopters zip through the sky and bullets trace arcs across the horizon.

The sound of explosions, sirens, and crying mothers became part of everyday life.

“You could see soldiers with guns, grenades … even when you stepped outside your front door,” he recalls.

The smell of war lingered too — burnt flesh, gunpowder, rot. Even in his 70s, Nguyen can still remember them now.

The fighting happened day and night. Eventually, he says, he joined the fight out of a sense of duty.

“I always told my soldiers: ‘From now on, you and I are one family. My siblings are far away and if I fall, it’s you who will pick me up. No one else’,” he says.

South Vietnamese women and children wait under the scorching midday sun after being gathered by US Marines for relocation near Da Nang on 7 May 1969. Source: AP / Hugh Van Es

A peaceful childhood shattered

Like Nguyen, Le Quang Vinh never pictured becoming a soldier.

The now-78-year-old grew up in the rice fields of the Mekong Delta. His childhood was filled with football, kite flying, and tending his family’s buffaloes.

That serenity was shattered when the communist forces started appearing in his village at night.

“They assassinated our village officer, our teachers … even killed my dog,” Le says.

“My dog was innocent. They hit him with a gun and he died in front of me. I felt sorry — even for the animals.”

Le had once dreamed of becoming a teacher. But by the time he was a teenager, he was fighting for his life and his country.

“In our culture, we don’t leave. We must stay with our fatherland, and protect our ancestors’ graves,” he says.

“Our spirits were strong because we knew we were fighting for freedom and democracy.”

Three cherished photos of Le Quang Vinh show him in uniform during his military service, including a moment at the elite Rangers Course in Fort Benning, Georgia, in 1973. Source: SBS News / Christopher Tan

On 23 April 1975 — just days before the Fall of Saigon — a rocket exploded 10 metres behind him.

“It was a near miss,” he recalls.

“I was wounded from the fragments and in hospital for a few days, but they rushed me straight back to the front line because we were losing numbers fast.”

The final hours of Saigon

Those final days are seared into Le’s soul.

On 30 April 1975, his unit was ordered to protect Saigon from the advancing communist forces.

Rockets, mortars, and bullets rained from the sky.

I saw people with no hands, no legs. A hand, separated from a body, left on the street. It was hell on earth.

At 7pm, a soldier handed him a radio. South Vietnam’s President Duong Van Minh had surrendered.

“I was shocked. I cried. I yelled. I couldn’t believe it,” Le says.

“I looked around and saw soldiers drop their weapons and run. It started raining — just a drizzle — but it felt like the heavens were crying for our country.”

He later buried fallen comrades in Bien Hoa, including a young lieutenant whose wife jumped into the grave, begging to die with him.

“I prayed to God to help us survive. I still cry when I think of that day.”

Re-education, resistance, and survival

Both Le and Nguyen were eventually captured and sent to communist re-education camps — brutal facilities that became known for forced labour, starvation and psychological torment.

Le, like many others, was told to attend a camp for a few days, instead he was imprisoned there for three years.

“They said it was education, but we didn’t learn anything. It was torture,” he says.

“We dug canals along the Cambodia border. People died [doing so].

“One friend had a bad toothache. They used pliers and there was lots of blood and crying, and he [the friend] told us that if we ever got sick, not to say anything.”

A North Vietnamese tank rolls through the gate of the Presidential Palace in Saigon, signifying the fall of South Vietnam. Source: AP / DC5

While imprisoned at the camp, Le warned others not to escape.

“Those who tried got shot. Their bodies were left on the ground as a warning,” he says.

“I told my friends, ‘You’re just escaping a small jail to enter a bigger one'”.

Even after Le and Nguyen were released from the camp, they were subject to constant surveillance by the Viet Cong.

Nguyen’s father told him to marry quickly, or risk being imprisoned again. So he did.

In 1985, he sold everything he owned for eight pieces of gold — to buy passage to Australia for his wife and two young children.

To reach Australian shores — some 4,800km from Vietnam — he and his family would have to make a perilous journey by boat.

Thanh Nguyen and Hong Kim Dong on their wedding day in Vietnam, following Nguyen’s release from a re-education camp. Source: Supplied / Thanh Nguyen

They crammed into the vessel along with more than 80 others.

“Everyone had to lie down side-by-side like fish,” Nguyen recalls.

“It was a very rough ride — the waves were huge, and you could tell the boat wasn’t built to handle those conditions.”

He says they lived in constant fear of encountering Thai pirates, who were known for preying on women and children.

“I was so scared for my wife and two young kids,” he says.

“But luckily, we weren’t targeted.”

The treacherous conditions took a devastating toll.

So many people got sick at sea — some even died. We had no choice but to throw the bodies overboard.

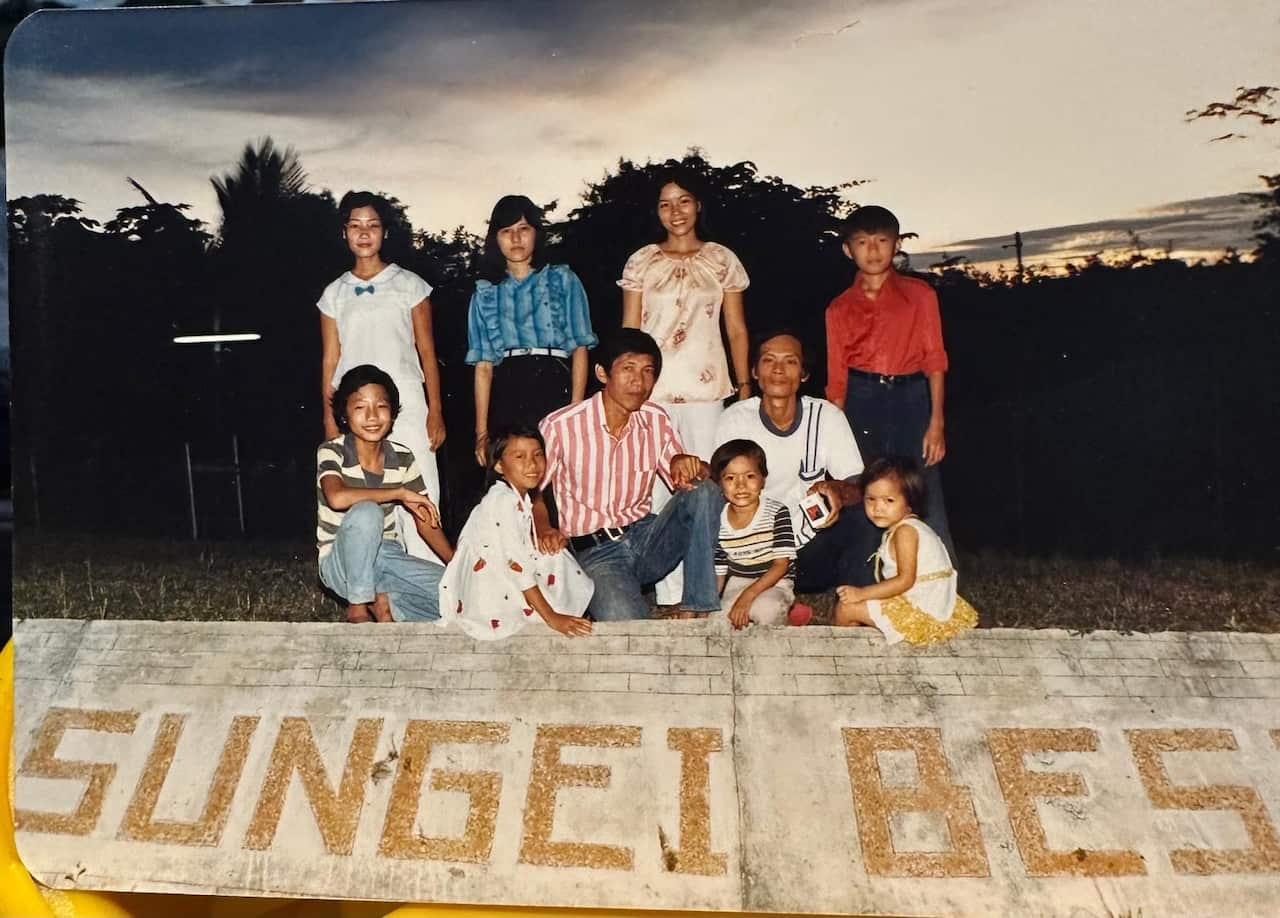

After surviving the journey, the Nguyens arrived in Malaysia, where they spent three months at Sungei Besi camp on the outskirts of Kuala Lumpur — a facility that felt more like a detention centre — waiting for their refugee applications to be approved.

They were eventually resettled in Perth, where they had family already living.

“I remember the date we arrived clearly — September 19 1985,” Nguyen says.

“The very next day, we went straight to work picking strawberries at a farm.”

Thanh Nguyen with his wife and two children and others at Sungei Besi camp in Malaysia, 1985. Source: Supplied / Thanh Nguyen

Reflecting on the journey, he says: “It was scary and dangerous, but it was better than living without freedom.”

Risking everything for freedom

Le also tried to escape Vietnam by boat.

His first attempt ended in disaster when a violent storm struck, capsizing the boat and nearly claiming the lives of his wife and two young children — then-aged three and four — his sister and nephew.

“From 1am to 3pm, we fought to survive,” Le recounts.

“The waves smashed us … the fuel tank sank and in the end, we drifted back to the same river mouth we came from.”

Undeterred, he and his family tried again a month later, this time joined by 45 others; mostly women and children.

After six harrowing nights at sea, they reached the Malaysian coast.

But their initial relief quickly turned to fear. A police boat intercepted them, and an officer asked if anyone could speak English.

“I put my hand up,” Le says.

“He asked me why I wanted to come to Malaysia. I told him: ‘Because I know Malaysia is a free country’. He said, ‘Malaysia is a communist country too’. I argued: ‘I don’t think so; you’re carrying an American pistol’.”

Then he pulled it out, pointed it at my head and said, ‘You must move back to your country or die here.’

A navy vessel arrived, tied up their boat and towed them two hours back out to sea before abandoning them.

Le says they spent the rest of the day navigating farther down the coastline until they saw people working on a distant farm. Jagged reefs made it impossible to bring the boat in.

“I decided to swim to shore to speak with the farmers, but they only spoke Chinese,” he says.

With help from an elderly Chinese man on board who acted as interpreter, Le says they were told they could land — but only if they sank the boat and left the area quickly.

That night, Le led the group to a remote shoreline, guided the women and children safely to land, and sank the boat offshore.

The next day, he flagged down a car and explained they were refugees with no food or water. Local residents brought biscuits and water and alerted the authorities.

The group was then transferred to the overcrowded Kuantan refugee camp.

Thanks to Le’s strong English, he was appointed camp leader and helped process the paperwork for 645 refugees ahead of a visit by the Australian High Commission.

His family was chosen for resettlement in Perth, which ended their five-week ordeal in Malaysia and marked the beginning of their new life in Australia.

Australia opens its arms

Le and his family were among the first wave of Vietnamese refugees welcomed into Australia under then-Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser’s humanitarian resettlement program in 1978.

It was a significant turning point in Australian history — coming just five years after the end of the White Australia Policy.

“To us, he [Malcolm Fraser] is like a lifesaver,” says Carina Hoang, a former refugee and now Special Representative to the UN Refugee Agency.

“His decision changed everything. We will always be grateful.”

Former refugee and UNHCR Special Representative Carina Hoang holds a book she authored, chronicling the powerful stories of Vietnamese refugees. Source: SBS News / Christopher Tan

Hoang was just 16 when she fled Vietnam with her two younger siblings. Her father, who was serving in the South Vietnamese military, had been imprisoned without trial for 14 years.

After the capture, the communists seized their home. They became homeless overnight.

“The day Saigon fell, April 30 1975, changed our lives forever. It was the end of the war … but the beginning of unimaginable loss,” Hoang says.

Just one night before, her mother, cousin, and siblings had made it to the US embassy in Saigon.

They waited 24 hours for their turn to evacuate in the helicopter — but were told they missed the last one.

Mobs of Vietnamese people scale the wall of the US Embassy in Saigon, trying to get to the helicopter pickup zone, just before the end of the Vietnam War on 29 April 1975. Source: AP / Neal Ulevich

They walked back home in silence. Hours later, the South Vietnamese government surrendered.

Hoang’s mother, a parent of seven, couldn’t get a job or register a business under the new regime.

They tried to leave, but that too was fraught: the family was scammed multiple times by people offering fake boat passages. Hoang says she was once kidnapped and held captive for 30 days by a smuggler they had paid.

“When a country is at war, most of the men are out fighting. The women are left to hold everything together,” Hoang says.

Vietnamese women are strong, resilient — but during the war, they were tested beyond their limits.

When she and her family eventually got a boat, their journey across the sea was no easier.

“We were chased by pirates; hit by violent storms. At times, we thought no one would make it.”

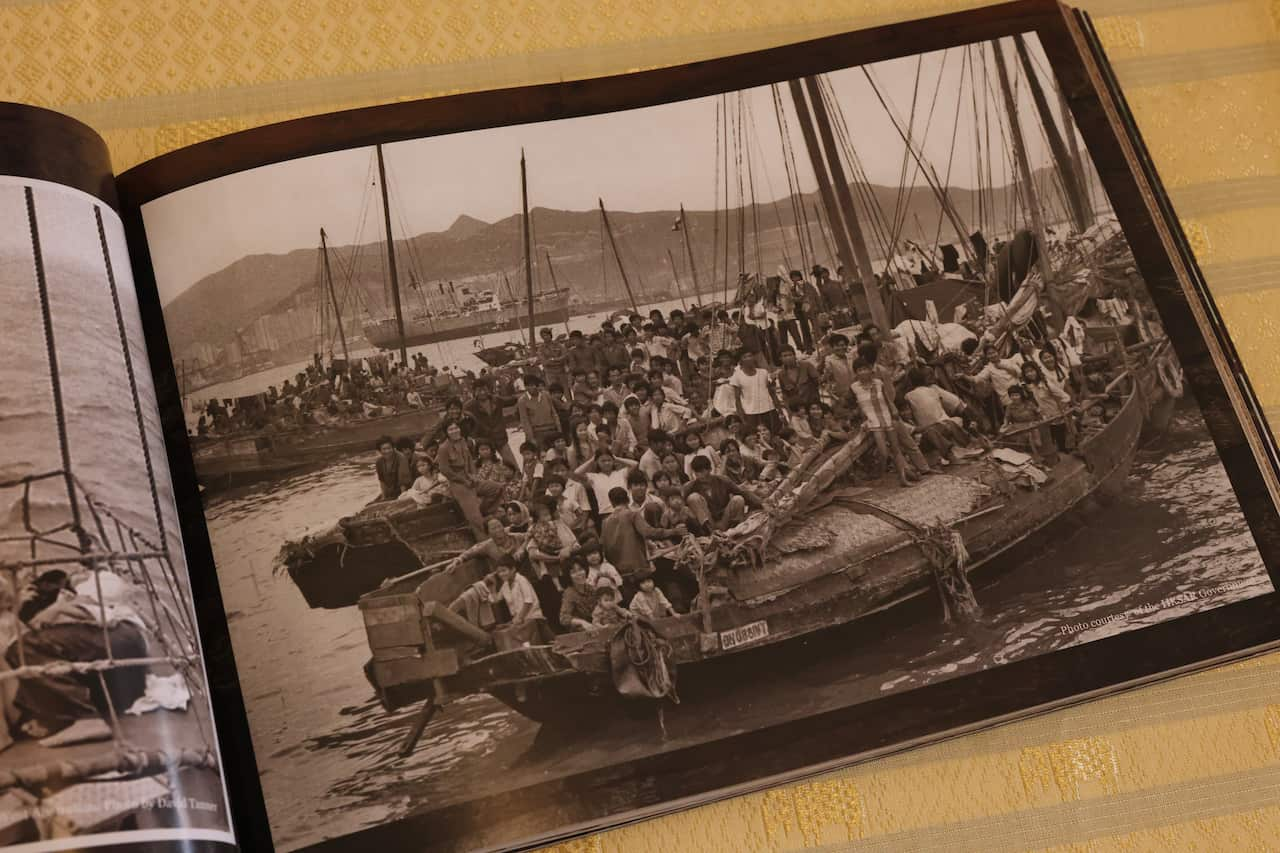

A crowded boat of Vietnamese refugees drifts at sea — one of many powerful images featured in Carina Hoang’s book documenting the perilous journeys of those who fled Vietnam in search of freedom. Source: SBS News / Christopher Tan

Hoang says their boat was shot at on 2 June 1979 by Malaysian authorities and towed back out to sea.

Eventually, they docked on an island off Indonesia with no facilities — just jungle. Hoang says over the period of time she was stuck on the island, more than 200 people died of disease and starvation.

“More than a million Vietnamese people attempted to flee by boat. It’s believed at least a third didn’t survive the journey,” Hoang says.

She and her two siblings were eventually accepted by the United States in 1980, where she faced the challenges of resettlement, learning English and adjusting to a new culture while carrying the emotional weight of having left her family behind.

After 26 years in the US, a return trip to Vietnam led her to meet her husband and the couple later settled in Australia in 2016.

Finding peace far from home

Fifty years on, Hoang, Le and Nguyen are all leading peaceful lives in Perth.

They’ve raised families, found work, and rebuilt what war had torn apart. But the pain remains.

“I’ve never returned to Vietnam,” Nguyen says.

“Too many sad memories.”

Thanh Nguyen arrives at Perth International Airport in 1985, with his wife Hong Kim Dong and their three-year-old daughter Thom following close behind — marking the beginning of a new life in Australia. Source: Supplied / Thanh Nguyen

While the pain of war did not end with the Fall of Saigon, for those who fled — and those who welcomed them — it also marked new beginnings.

Tens of thousands of Vietnamese people came to Australia following the war and as of June last year, there were just under 300,000 Vietnamese-born people living in Australia, according to the Department of Home Affairs.

Hoang says behind every resettled Vietnamese family is a story of survival, sacrifice, and unimaginable resilience.

“They arrived with nothing — but their values, their strength, and their stories helped shape the multicultural Australia we know today.”

Thanh Nguyen leads the Vietnam Veterans Association of WA during the 2024 Anzac Day march in Perth. Source: SBS News / Christopher Tan

For the latest from SBS News, and .