Share and Follow

A tragic discovery was made when 19-year-old James was found deceased on K’gari, known previously as Fraser Island, in Queensland.

Subsequently, Queensland’s Department of the Environment and Tourism announced plans to euthanize the dingoes involved after noting their “aggressive behavior.”

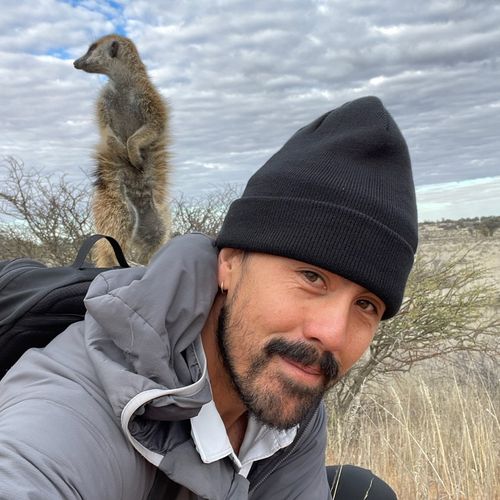

Dr. Daniel Hunter, an ecosystem biologist and wildlife filmmaker, criticized the decision, arguing it punishes dingoes for their natural predatory instincts.

“This is merely a temporary fix and doesn’t tackle the core issue, which is the lack of proper education and the unchecked behavior of tourists,” he remarked to 9news.com.au.

Dr. Hunter, who has spent extensive time studying dingoes in Australia, observed that the majority tend to avoid human contact.

The small population on K’gari, however, have become accustomed to encountering tourists and may associate them with food found at campsites.

Being overexposed to humans has made the dingoes on K’gari more comfortable getting close and that can be dangerous – or deadly.

Hunter acknowledged the tragedy of James’ death but said ”something like this was always going to happen, it was just a matter of when”.

But a cull won’t prevent it from happening again.

“There really is no good that can come from the cull,” Hunter said.

“It’s quite barbaric and primitive and shows that we haven’t actually listened to traditional owners or the best science available.”

He’s not the only expert who feels that way.

Dr Mathew Crowther, professor of Quantitative Conservation Biology in the School of Life and Environmental Sciences at the University of Sydney, called the cull unwise.

“Culling will do little to prevent aggressive behaviour, as it does not address the underlying causes of dingo–human conflict.”

Associate Professor Bill Bateman, from the Behaviour and Ecology Research Group in the School of Molecular and Life Sciences at Curtin University, agreed.

”It is unlikely that culling the dingo pack will have any effect other than driving down the dingo population on K’gari,” he said.

And that could have devastating impacts in the short- and long-term.

The dingo population on K’gari is already small and its genetic diversity is low, meaning the cull could pose a very real threat to its long-term survival.

Euthanising the dingoes involved could also destabilise pack structures on the island, especially if one or more dominant animals are put down.

The cull could also have a flow-on effect on other wildlife on the island.

“You can’t just take out the top predator and expect there to be no ecological repercussions,” Hunter said.

He’s calling for education instead of euthanasia.

A cull won’t change the behaviour of an apex predator, but education can change how humans interact with them.

“I actually think there should be some kind of mandatory education before you enter the island,” Hunter said.

“Whether that be on the ferry with a ranger that discusses the situation with respect to dingoes and camping and staying safe … I think that could really help.”

Other experts agree that education will go a long way towards making tourists safer on K’gari.

Crowther echoed the call for clearer, safer rules instead of lethal control, and Bateman suggested a cap on visitor numbers.

Hunter also advocated for increased consultation with local Indigenous groups on how best to manage dingo populations.

“The traditional owners of the land there have a really good understanding of how to interact with dingoes and how to respect them,” he said.

“I think First Nations people should have a the majority say up there.”

NEVER MISS A STORY: Get your breaking news and exclusive stories first by following us across all platforms.