Kaur has emphasized that her choice isn’t rooted in a lack of faith in Australia. Instead, it’s a means of preserving a vital link to her cultural heritage. For her, this action symbolizes safeguarding something irreplaceable, a sentiment that resonates deeply with her personal history.

The decision was influenced by unsettling stories of burglaries circulating among her community on WhatsApp groups. Coupled with the rising gold prices, these factors have contributed to her growing anxiety about retaining such valuables in her current location.

Her actions reflect a broader sentiment of caution within her community. “People aren’t liquidating — they’re safeguarding,” another community member shared with SBS News, underscoring the protective instincts driving such decisions.

“They see their family vault in India as safer than stowing away gold in obscure corners of the house. Even if they purchase here or in India, they prefer to keep that jewellery with their parents in India.

“And this trend is not limited to Australia. It’s the same story everywhere for migrant families, be it in the United Kingdom or Canada.”

With working parents and school-going children leaving some homes unoccupied for most of the day, a family vault in India — guarded by relatives — is often viewed as more secure than a home safe in Australia.

Gold as culture, not commodity

The yellow metal has always held deep significance in Indian families — gifted at weddings, inherited by daughters, and stored as a safety net for hard times. Even abroad, those traditions endure.

Meena Chavan, an economic anthropologist and associate professor of international business and entrepreneurship at Macquarie Business School, said for Indian Australian families, gold isn’t just a financial asset, it’s an emotional and cultural inheritance that “embodies stability, heritage, and belonging”.

“India consistently ranks as one of the world’s largest gold consumers, responsible for around 25 per cent of global demand. This is primarily driven by a love for gold jewellery, which is an essential part of Indian weddings, festivals, and religious ceremonies,” she told SBS News.

She said for some, sending gold “home” is about more than economics.

“It reflects deep trust in family networks and cultural continuity. It’s not only about financial security but emotional security, anchoring wealth within family ties and the social fabric of the homeland. For many, it represents confidence in kinship rather than in formal systems,” Chavan said.

But for others, there can be a darker side when it comes to gold.

Supriya Singh is an adjunct professor at the Department of Social Inquiry at La Trobe University and a founding member of the Multicultural Women’s Alliance Against Family Violence.

She said for some families, the jewellery that represents security and heritage can quietly become a means of exerting power over them.

“In my research on family violence among Indian women in Australia, a sign of economic abuse is that the woman’s gold is taken away by the husband or his family,” Singh told SBS News.

“Often she is told the gold will be kept safely in her mother-in-law’s or brother-in-law’s safe-deposit locker, to which the woman has no access.

“Women also tell that the husband stole her jewellery as he left home because of an intervention order. Getting the jewellery back is nearly always impossible. The woman not only loses in terms of wealth, but also loses jewellery which has been handed down her mother’s line for generations.”

Jewellery theft

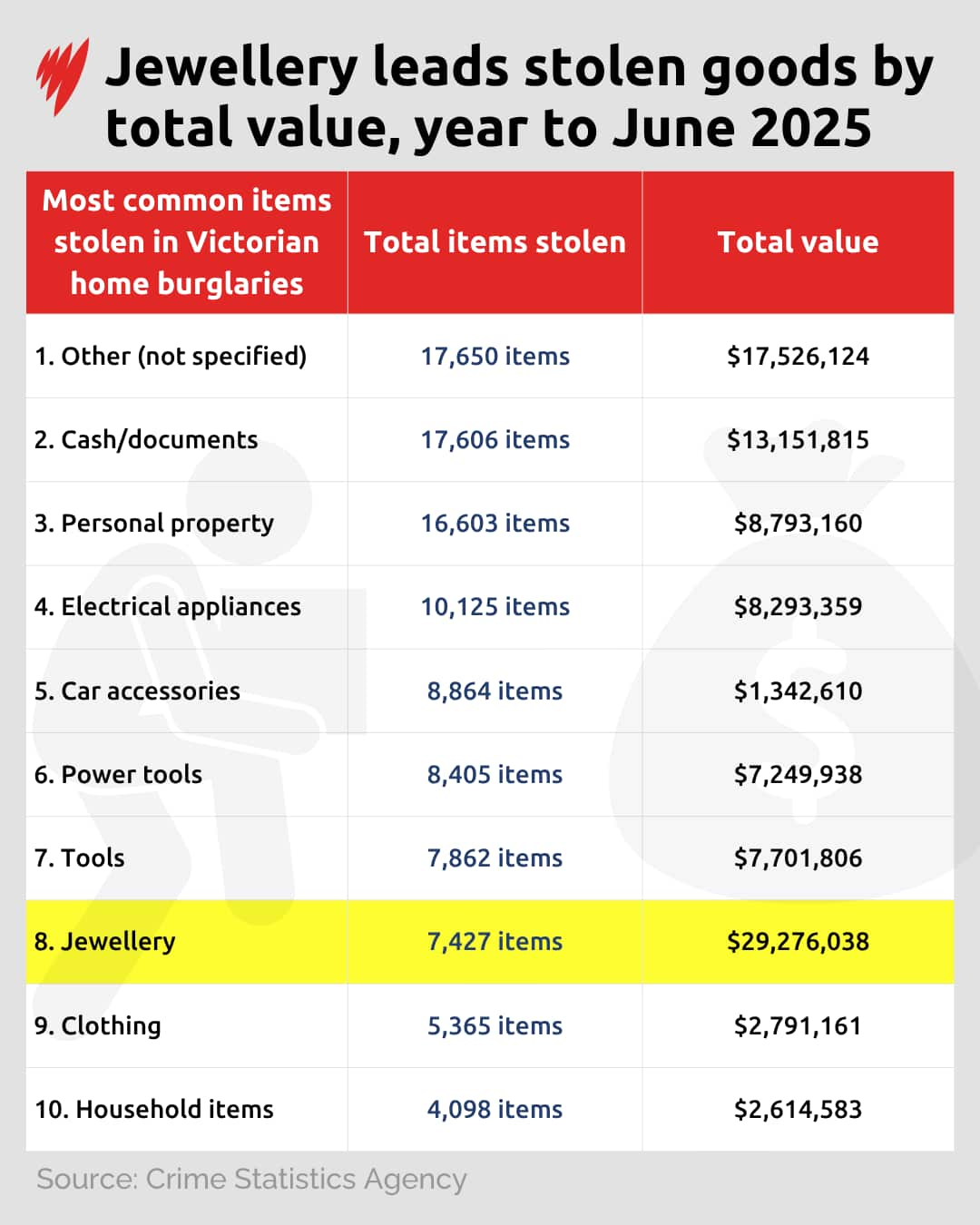

According to the latest Crime Statistics Agency Victoria (CSA) data, jewellery remains the second-highest priority target for thieves in Victoria, led only by cash.

Between March 2024 and 2025, nearly $29 million worth of jewellery was reported stolen from Victorian properties. The hardest-hit area was Boroondara in Melbourne’s inner-east, with $3.3 million stolen, followed by nearby suburbs such as Hawthorn, Balwyn North, and Kew.

Nearly $29 million worth of jewellery was reported stolen from Victorian properties in the year to June 2025, according to data from the Victorian Crime Statistics Agency. Source: SBS News

CSA data shows there were 30,545 burglaries of Victorian homes in the year to June 2025, up 13.9 per cent from 26,812 the previous year.

A Victoria Police spokesperson told the Herald Sun in July that simple security measures could prevent most burglaries.

“Since the start of the year, around 65 per cent of all aggravated home burglaries in key hotspots have either been due to unlocked doors/windows, or an unsuccessful attempt when the offender realised the home was locked,” the spokesperson said.

More than $55 million worth of jewellery was stolen from Victorian homes in 2017, but CSA data shows the figure has declined steadily since — although valuables of this kind remain a consistent target.

Simreet Thukral, a Melbourne resident, had $8,000 worth of gold jewellery stolen from her home while on a trip to Adelaide in 2018.

“Some of it was heirloom, passed down through generations,” she told SBS News.

Melburnian Simreet Thukral had gold and diamond jewellery worth $8,000 stolen from her former home in Noble Park in south-east Melbourne when she went on a trip to Adelaide. Source: Supplied

Despite filing a police report, the pieces were never recovered.

“The emotional loss was heavier than the monetary one. It’s terrifying to think our most precious possessions could just vanish,” Thukral said.

While stories like Thukral’s are prompting some people to reconsider where they store gold, not all Indian Australian families want their jewellery stored an ocean away.

Sydney resident Sanil (who requested his last name be withheld) said he doesn’t identify with the concept of sending or storing gold in India. The 38-year-old said he would rather invest in a private vault and upgrade his home security.

For him, the question is simple: what’s the point of owning jewellery you can’t wear?

“We’d rather secure it here than send it somewhere we can’t access it for weddings, festivals, or celebrations,” he told SBS News. “Gold is meant to be worn, not hidden or stored for posterity.”

Coburg-based jeweller Harshudeep Singh said moving gold across borders also requires attention to customs duties and declaration rules, particularly for larger quantities.

“When you send jewellery to India through courier companies or similar means, you will have to pay taxes and duties, which is quite a costly affair,” he said.

Ekjot Kaur said sending her gold jewellery to her family in India is about protecting a tangible connection to her roots and cultural heritage. Source: Supplied

But for some, like Kaur, the reassurance of family custody outweighs the logistical hurdles. She said sending her gold home isn’t about distrusting Australia — it is about protecting a tangible connection to her family and her roots.

“My jewellery is more than wealth. It’s memory, it’s love, it’s the story of who we are. Losing it would feel like losing a part of myself,” she said.

“Distance makes me feel safer.”

Financial and regulatory considerations

According to Chavan, the mindset reflects more than security concerns.

“This is part of a broader pattern of diaspora wealth management where emotional and financial rationalities intertwine. First-generation migrants often maintain assets in both countries, while younger generations tend to be more globally diversified, treating wealth less as tradition and more as a strategy,” she said.

India allows limited quantities of gold to be brought in duty-free, but tighter reporting rules mean families prefer small, discreet transfers rather than large shipments.

Professor Santosh Jatrana (not pictured) from the Deakin Institute for Citizenship and Globalisation said factors such as the cost of storage and insurance can play a major role in the decision to transfer gold within migrant communities. Credit: Hindustan Times via Getty Images

Professor Santosh Jatrana from the Deakin Institute for Citizenship and Globalisation said policy factors also play a major role in the decisions related to the transfer of gold within migrant communities.

“In Australia, the limited availability of bank safe-deposit services and high fees for private vaults make secure storage both costly and inconvenient,” she told SBS News.

“For instance, annual locker rent in India ranges from about 1,500 rupees to 12,000 rupees, depending on size, location and the bank, which works out to roughly $26 to $207 each year — a sum many find affordable.”

Jatrana said insurance policies could also affect these decisions.

“A standard home insurance provides minimal coverage for high-value jewellery unless each item is specifically listed and valued, making overseas safekeeping comparatively easier.”