Achieving net zero is critical to minimise the impacts of global emissions on Australia, with failure risking putting us in “difficult territory”, experts say.

Until last week, the net zero by 2050 emissions reduction target had bipartisan support, with the Albanese government legislating associated targets in 2022.

However, the climate wars were reignited with the Liberals forced to drop net zero from their energy platform after the Nationals walked away from the policy.

In a policy document released on Sunday, the Opposition said it would instead reduce emissions “on average year on year, for every five-year period of Australia’s Nationally Determined Contribution”.

The specific reduction in emissions remains unspecified, with authorities only noting that efforts will align with Australia’s best interests by contributing equitably, taking into account the genuine performance of OECD nations.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said the move creates investment uncertainty and the Opposition is “choosing to take Australia backwards”.

To many, the notion of achieving net zero emissions is synonymous with addressing climate change effectively. Thus, if these targets were abandoned and global net zero was not reached, what consequences might follow?

The concept gained traction when the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) outlined scenarios emphasizing the critical need to keep global temperature rise below 1.5 degrees Celsius to avoid reaching potentially disastrous “tipping points” that could trigger uncontrollable warming.

The federal government has committed to achieving net zero by 2050 — meaning the amount of greenhouse gases released will be balanced by those removed from the atmosphere — and is pursuing an interim target of a 62 to 70 per cent reduction by 2035, compared to 2005 levels.

A scientific term from the early 2000s, the concept of ‘net zero’ was referred to in the 2015 Paris Agreement, a legally binding international treaty on climate change.

The agreement aims to limit global warming below 2C, and ideally 1.5C by 2050 — a goal that net zero was an important part of.

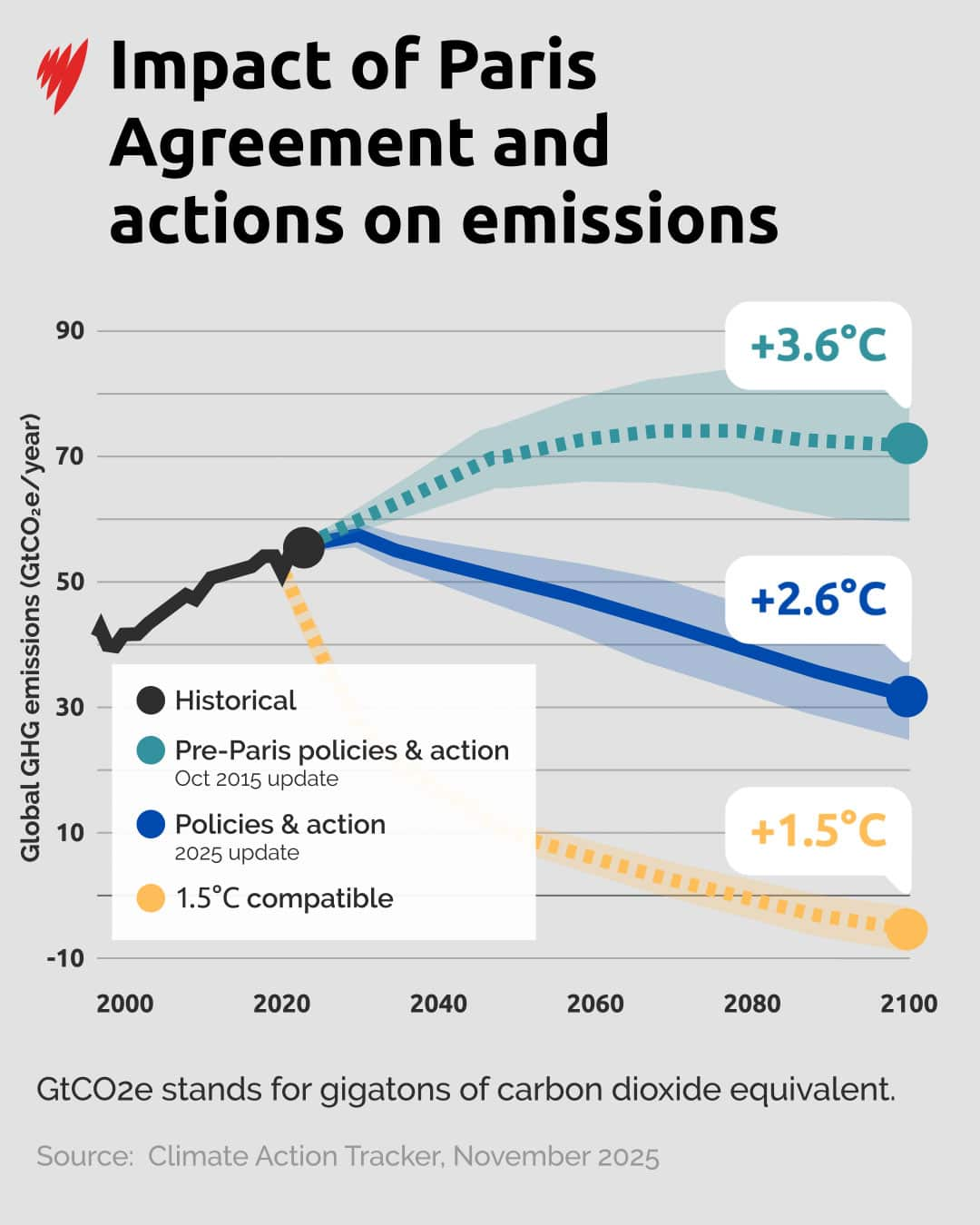

Thanks to current international agreements and initiatives, projections suggest a reduction in global warming by at least one degree compared to estimates prior to the Paris Agreement.

Current global agreements and efforts are projected to reduce global warming by at least 1 degree less than projected before the Paris Agreement.

James Hopeward, associate professor in environmental engineering at the University of South Australia, says net zero could also be achieved by reaching absolute zero, where no fossil fuel emissions need to be offset.

“But if we don’t get to absolute zero, then the net part of that is that we would be employing technologies like carbon capture to take that extra carbon out of the atmosphere,” he said.

He said speed is key, with drastic cuts to emissions needed to reach both the goal and reduce global climate impacts.

What’s at risk if we don’t reach net zero?

Australia’s first National Climate Risk Assessment (NCRA), released in September, spells out the dangers of allowing global emissions to continue rising. Achieving net zero is pivotal to the Paris target of keeping global warming close to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels.

The NCRA projects the impact of global warming increases by 1.5C, 2C and 3C, and the strain that these temperature increases would put on everything from agricultural output, to increased drought, higher deaths due to extreme heat, as well as a decrease in property values.

Hopeward said the report offers a best-case scenario and then demonstrates that if we don’t get to net zero by 2050, we risk approaching 2 or 3 degrees of warming, landing Australia “in much more difficult territory”.

“Whilst it might not seem that 1.5 degrees and 3 degrees are very different … It’s not a linear relationship. The set of risks don’t just double at 3 degrees, they often quadruple or more,” he explained.

Using the risk of coastal flooding as an example, at 1.5C it doubles, while at 3C it goes up by a factor of 14.

“There are these incredibly large disproportionate impacts that come from that extra one and a half degrees of warming,” he said.

Even if countries achieve net zero and lower global warming by 1.5C, the NCRA projects that Australia will experience an increase in storms, ecosystems such as reefs will be under stress and there’ll be a rise in smoke impacts from bushfire activity and impacts to water security.

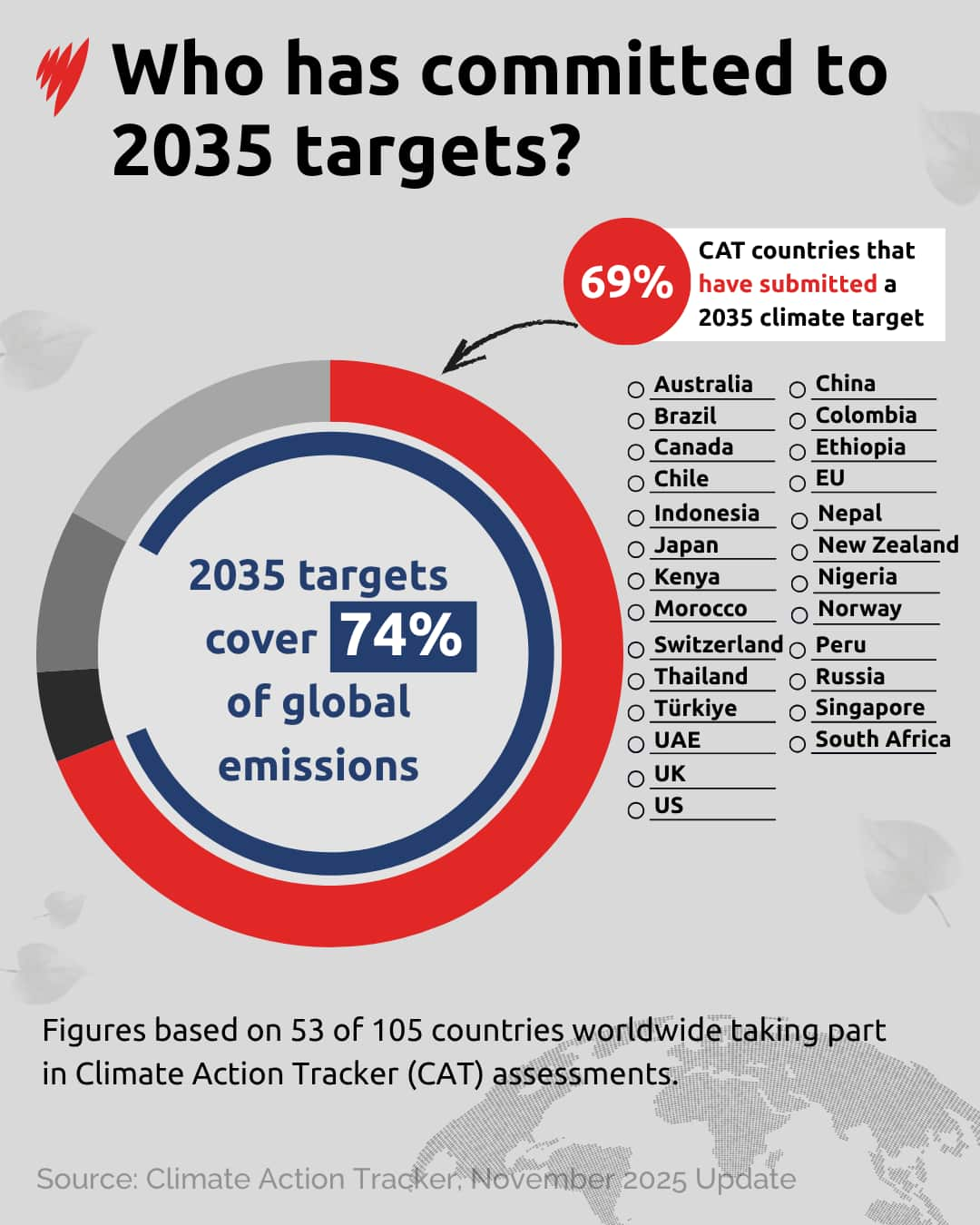

Existing 2035 targets account for 74 per cent of global emissions.

Based on current global reduction agreements — which cover roughly 74 of global emissions — Climate Action Tracker, an indpendent scientific project that tracks government action on climate, predicts global temperatures will rise by 2.6C.

Anna Malos is the country lead for the Melbourne-based Climateworks Centre, an organisation that researches solutions and independently advises governments and businesses on the best way to reach net zero.

She says outside the physical impact of a warming world, a failure to reach net zero will have economic impacts.

“Businesses and investors need to understand what direction the economy is heading in and where you’ve got agreement that sort of everyone is working in the same direction,” she said.

“Then businesses and investors, they have more confidence they can invest when they need to, and the whole economy becomes more productive and more efficient.”

Would bills go down if we scrap net zero?

The Coalition argues that the renewable transition is costing Australians through higher energy bills as part of its justification for axing net zero.

Malos says “bills would have gone up anyway” as Australia rushes to update an energy system full of aging coal-fired generators.

“Global difficulties arising from the pandemic, the war in Ukraine, and the speed at which those coal-fired generators are becoming less reliable, has meant that a rapid transition is even more important. It’s also made some of those changes more costly,” she said.

“Some of the evidence shows they’d [bills] would have gone up a lot more if we hadn’t had the levels of renewable electricity we’ve got in the system.

“Replacing coal fire generation with solar, wind and batteries is now the best way to create an affordable, reliable electricity system.”