Share and Follow

“The stunts we do in deathmatch wrestling are only limited by our imagination,” Bateman tells SBS News.

When Joel Bateman isn’t working his government job, he’s making himself bleed in unique and gruesome ways. Source: Supplied / Jake Hurdle (@jhmedia.jpeg)

“The fluorescent light tube is the staple of modern deathmatch wrestling. It’s the same thing you’d find in your garage. But all the green initiatives are actually making them harder to find and more expensive — so we have to get more creative,” Bateman says.

“I’ve only done whipper snippers three or four times. Every time I do it, I don’t remember it being that bad the last time. And then I do it and I go, ‘Oh, it hurts exactly as much as I thought it did last time’,” Bateman says.

It’s like being pink-bellied 150 times in the space of a quarter of a second.

The now 36-year-old estimates he’s performed over 200 deathmatches — a number that accelerated significantly since the launch of his own wrestling promotion (business), Deathmatch Downunder.

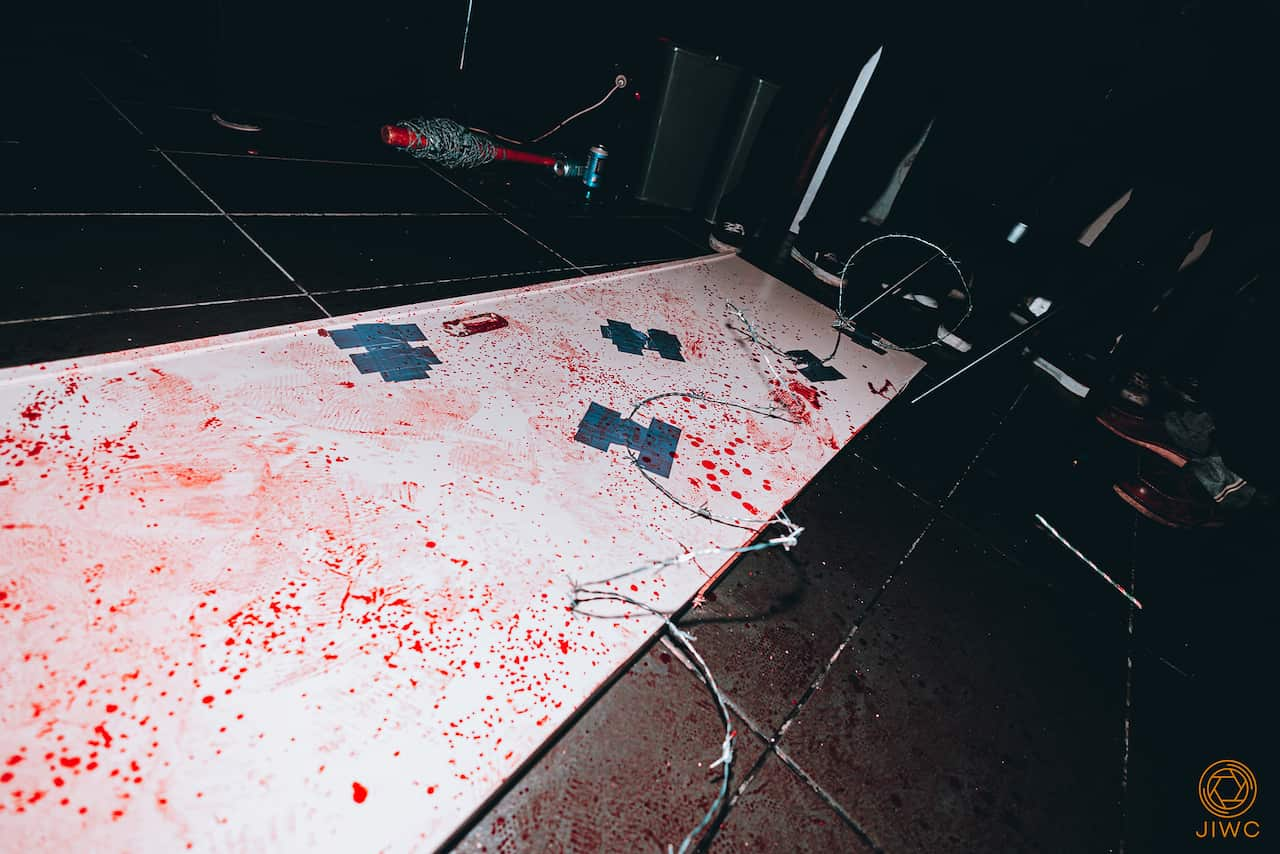

In the world of deathmatch wrestling, anything goes — even eating glass tubes, like Japanese professional wrestler Abdullah Kobayashi here. Source: Supplied / Jake Hurdle (@jhmedia.jpeg)

At first glance, anyone could think death matches are just blood, gore and violence — and, look, that’s partially right — but for those in this niche little world, it’s about so much more.

Welcome to the world of deathmatch wrestling

“It’s like the Police Academy stunt show at Movie World, crossed with a live-action horror movie with the performance art of pro wrestling.”

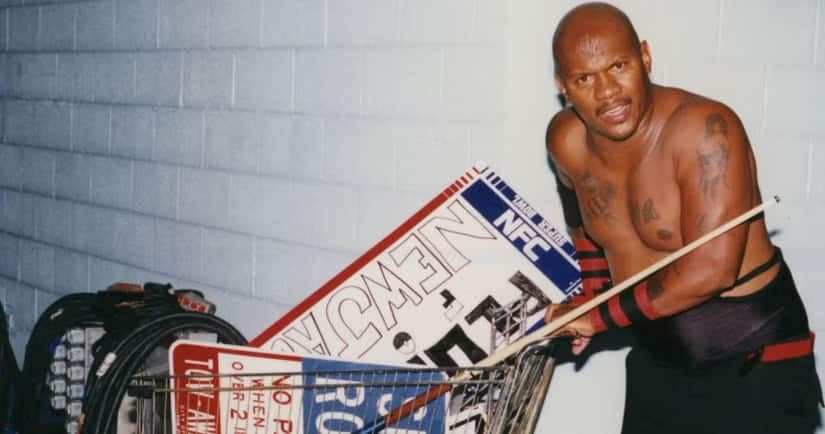

The first time Jordan Whyte and Joel Bateman wrestled each other in a deathmatch, Jordan got a fluorescent light tube straight to the face. Source: Supplied / Jaden Lee (@jiwcphotos)

While professional wrestling is pre-determined (not to be confused with fake), all props used in deathmatch wrestling are 100 per cent real. Matches are a hotbed of creativity with no rules — except that there needs to be blood. And lots of it.

“Everything is legitimate. Through repetition, you learn how to take these household objects and use them in a way that you could draw blood with them safely — like the most [bonkers] surgeon you’ve ever seen,” he says.

A double life

“The first time I got hit was with the glass tube. I thought it was really hot in there.

Then I wiped the sweat from my face and was like, ‘Oh, I’m gushing blood’.

“Then Joel set his knee on fire and kneed me in the face.”

Jordan Whyte first entered the niche world two months ago in a match with legacy deathmatcher, Joel Bateman. They say trust and a good relationship are key components of the process. Source: Supplied / Jaden Lee (@jiwcphotos)

The venue held about 120 people. One spectator was a university classmate of Whyte’s, who was shocked to see the soon-to-be primary school teacher dripping blood on stage.

In the grand scheme of things, a chair on the head is the least of Whyte’s problems. Instead, he says there are three weapons that rank the highest on the pain scale.

Skewers in the head is one of the most painful stunts in deathmatch wrestling, Jordan Whyte says. (Pictured: Jordan Sampson and Aidan Osbourne). Source: Supplied / Jaden Lee (@jiwcphotos)

The first is wooden skewers, which are pierced into the victim’s forehead.

The third: a Guitar Hero guitar, which Whyte describes as “weirdly painful”.

In deathmatch wrestling, anything goes: even Guitar Hero. Source: Supplied / Jaden Lee (@jiwcphotos)

“It was very solid. When I got it off Facebook Marketplace, the lady was like, ‘Are you sure you want it? It doesn’t work.’ And I was like, ‘That’s fine, I don’t need it to work’,” Whyte says.

Controversial, even in the wrestling world

It’s exactly what it sounds like on the tin: barbed wire surrounded the ring and triggered explosions when touched. One iteration featured a countdown timer that, at zero, would cause the entire ring to explode (yes, with people still inside).

Each week, matches won with DIY weapons became the standard, making the promotion synonymous with the bloody and violent subculture, but also a haven for those who wanted a more brutal viewing experience. Both Whyte and Bateman credit ECW as the inspiration for their own careers.

New Jack was one of the most controversial hardcore wrestlers of all time and carried the label of one of the most dangerous and unpredictable people in the industry’s history. Source: Supplied / ECW

But it was not without risk: one ECW house show resulted in a 17-year-old aspiring wrestler being injured after he was ‘bladed’ (the act of intentionally and discreetly cutting oneself in a match to draw blood for dramatic effect) too deeply by another wrestler, New Jack, severing two of his arteries and almost killing him.

A year later, in a rematch, New Jack allegedly tried to kill Vic Grimes by intentionally going off-script, tasing him and throwing him off the scaffolding. In the wrestling documentary Dark Side of the Ring, New Jack said: “I was trying to throw his ass to the floor … He was lying in the ring and I told him, ‘Now we’re even, you f**cker.”

Jordan Whyte and Joel Bateman were both inspired by Extreme Championship Wrestling in the 90s, which became synonymous with deathmatch-style wrestling. Source: Supplied / Jaden Lee (@jiwcphotos)

‘Organised barbarism’ unfairly ‘demonised’

Some say that’s for good reason.

Deathmatch wrestling has its share of critics — even from those within the professional wrestling industry. Source: Supplied / Jaden Lee (@jiwcphotos)

Critics of deathmatch wrestling say it is inherently dangerous, violent for the sake of violence, and a lesser form of professional wrestling. Others say it’s for the talentless and has a low bar for skill. Some say it’s dangerous for fans, gives wrestling a bad name, or is just plain repetitive with a limited repertoire.

But Bateman says the subgenre is unfairly “demonised”.

I take a lot of pride in the fact that we have such a safe space — both for our performers and fans.

“Any fans who have gotten little cuts and scratches from flying glass absolutely love it … we’ll ask if they want a bandaid and they’re like, nah, we’re fine. We love it. This is why we come here.”

Surprisingly, glass is one of the safer weapons in deathmatches. Joel Bateman says it’s because they use tempered glass, which “won’t cut you to the point where you need to go to the hospital”. Source: Supplied / Jake Hurdle (@jhmedia.jpeg)

Bateman says the Australian scene was almost decimated in 2002 after a “disgruntled wrestler” went to the media about a particular “family-friendly” deathmatch, calling it “organised barbarism” and claiming blood was sprayed on the crowd. In three weeks, crowd numbers went from 1,200 people to 80.

“[Attitudes] are starting to change and people are becoming more accepting of it,” he says.

More than blood

“If you’re a face in a crowd, people feel comfortable saying racist shit.”

At first glance, deathmatch wrestling might look like needless violence. But for Joel Bateman, it’s also about expressing his First Nations identity. Source: Supplied / Jaden Lee (@jiwcphotos)

But Bateman says that launching the promotion at the start of the Black Lives Matter movement was a “turning point” for him and gave him the confidence to show himself wholly on stage.

“I remember finishing the match and just bursting into tears and then opening my eyes and seeing there was a standing ovation.

It was this culmination of 18 years of suppressing my genuine self.

“There’s probably more death match wrestlers in the country than there are First Nations wrestlers in the country, which is something I’m trying to rectify. But it’s a very long and very slow journey to do so,” he says.

Joel Bateman never felt comfortable with his Aboriginality on display in the ring under he started Deathmatch his promotion (business). Now, he hopes to inspire other First Nations wrestlers in Australia. Source: Supplied / Jake Hurdle (@jhmedia.jpeg)

The promotion also started in the midst of professional wrestling’s own #MeToo movement — #SpeakingOut — which exposed systemic emotional, physical and sexual abuse in the industry.