Share and Follow

The downfall of Nicolás Maduro represents the peak of intensified U.S. efforts across multiple fronts over recent months.

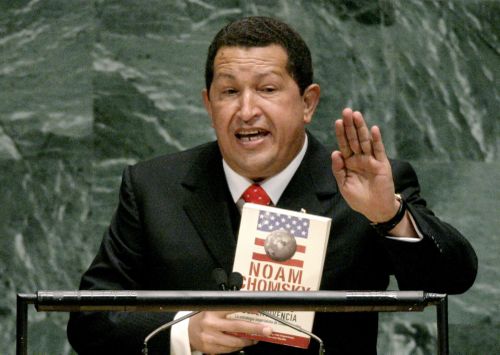

Throughout the closing months of his administration, Maduro was vocal about his belief that the U.S. was plotting to attack and invade Venezuela, aiming to dismantle the socialist revolution initiated by his predecessor and mentor, Hugo Chávez, in 1999. Like Chávez, Maduro depicted the United States as Venezuela’s chief adversary, condemning both Democratic and Republican administrations for any attempts to restore democratic practices in the country.

Maduro’s political journey began four decades ago. In 1986, he traveled to Cuba to undergo a year of ideological training, which was his only formal education beyond high school. Upon returning, he took a job as a bus driver for the Caracas subway system and quickly ascended to a union leadership position. During the 1990s, Venezuelan intelligence labeled him as a leftist radical with close connections to the Cuban government.

Maduro eventually left his position as a bus driver to join the political movement organized by Chávez, who had received a presidential pardon in 1994 after leading a failed and violent military coup. Once Chávez assumed the presidency, Maduro, who had once been a youth baseball player, swiftly climbed the ranks within the ruling party. He spent his first six years as a member of the legislature before becoming president of the National Assembly, later serving six years as foreign minister, followed by a brief stint as vice president.

In Chávez’s final address to the nation prior to his death in 2013, he designated Maduro as his successor, urging his supporters to vote for the then-foreign minister if he were to pass away. This choice took both supporters and critics by surprise. However, Chávez’s substantial electoral influence secured Maduro a narrow victory that year, granting him his first six-year term, though he never achieved the same level of adoration from voters that Chávez had enjoyed.

Chávez used his last address to the nation before his death in 2013 to anoint Maduro as his successor, asking his supporters to vote for the then-foreign affairs minister should he die. The choice stunned supporters and detractors alike. But Chávez’s enormous electoral capital delivered Maduro a razor-thin victory that year, giving him his first six-year term, though he would never enjoy the devotion that voters professed for Chávez.

Maduro married Flores, his partner of nearly two decades, in July 2013, shortly after he became president. He called her the “first combatant”, instead of first lady, and considered her a crucial adviser.

Maduro’s entire presidency was marked by a complex social, political and economic crisis that pushed millions into poverty, drove more than 7.7 million Venezuelans to migrate and put thousands of real or perceived government opponents in prison, where many were tortured, some at his direction. Maduro complemented the repressive apparatus by purging institutions of anyone who dared dissent.

Venezuela’s crisis took hold during Maduro’s first year in office. The political opposition, including the now-Nobel Peace Prize winner María Corina Machado, called for street protests in Caracas and other cities. The demonstrations evidenced Maduro’s iron fist as security forces pushed back protests, which ended with 43 deaths and dozens of arrests.

Maduro’s United Socialist Party of Venezuela would go on to lose control of the National Assembly for the first time in 16 years in the 2015 election. Maduro moved to neutralise the opposition-controlled legislature by establishing a pro-government Constituent Assembly in 2017, leading to months of protests violently suppressed by security forces and the military.

More than 100 people were killed and thousands were injured in the demonstrations. Hundreds were arrested, causing the International Criminal Court to open an investigation against Maduro and members of his government for crimes against humanity. The investigation was still ongoing in 2025.

In 2018, Maduro survived an assassination attempt when drones rigged with explosives detonated near him as he delivered a speech during a nationally televised military parade.

Bedeviled by economic problems

Maduro was unable to stop the economic free fall. Inflation and severe shortages of food and medicines affected Venezuelans nationwide. Entire families starved and began migrating on foot to neighboring countries. Those who remained lined up for hours to buy rice, beans and other basics. Some fought on the streets over flour.

Ruling party loyalists moved the December 2018 presidential election to May and blocked opposition parties from the ballot. Some opposition politicians were imprisoned; others fled into exile. Maduro ran virtually unopposed and was declared winner, but dozens of countries did not recognise him.

Months after the election, he drew the fury after social media videos showed him feasting on a steak prepared by a celebrity chef at a restaurant in Turkey while millions in his country were going hungry.

Under Maduro’s watch, Venezuela’s economy shrank 71 per cent between 2012 and 2020, while inflation topped 130,000 per cent. Its oil production, the beating heart of the country, dropped to less than 400,000 barrels a day, a figure once unthinkable.

The first Trump administration imposed economic sanctions against Maduro, his allies and state-owned companies to try to force a government change. The measures included freezing all Venezuelan government assets in the US and prohibiting American citizens and international partners from doing business with Venezuelan government entities, including the state-owned oil company.

Out of options, Maduro began implementing a series of economic measures in 2021 that eventually ended Venezuela’s hyperinflation cycle. He paired the economic changes with concessions to the US-backed political opposition with which it restarted negotiations for what many had hoped would be a free and democratic presidential election in 2024.

Maduro used the negotiations to gain concessions from the US government, including the pardon and prison release of one of his closest allies and the sanctions licence that allowed oil giant Chevron to restart pumping and exporting Venezuelan oil. The license became his government’s financial lifeline.

Losing support in many places

Negotiations led by Norwegian diplomats did not solve key political differences between the ruling party and the opposition.

In 2023, the government banned Machado, Maduro’s strongest opponent, from running for office. In early 2024, it intensified its repressive efforts, detaining opposition leaders and human rights defenders. The government also forced key members of Machado’s campaign to seek asylum at a diplomatic compound in Caracas, where they remained for more than a year to avoid arrest.

Hours after polls closed in the 2024 election, the National Electoral Council declared Maduro the winner. But unlike previous elections, it did not provide detailed vote counts. The opposition, however, collected and published tally sheets from more than 80 per cent of electronic voting machines used in the election. The records showed Edmundo González defeated Maduro by a more than 2-to-1 margin.

Protests erupted. Some demonstrators toppled statues of Chávez. The government again responded with full force and detained more than 2000 people. World leaders rejected the official results, but the National Assembly sworn in Maduro for a third term in January 2025.

Trump’s return to the White House that same month proved to be a sobering moment for Maduro. Trump quickly pushed Maduro to accept regular deportation flights for the first time in years. By the summer, Trump had built up a military force in the Caribbean that put Venezuela’s government on high alert and started taking steps to address what it called narco-terrorism.

For Maduro, that was the beginning of the end.