Share and Follow

The Miss Universe pageant, a staple since 1952, has witnessed numerous landmark moments. In 2024, trailblazers Khadija Omar from Somalia and Ashley Callingbull, the first Indigenous Canadian, both vied for the prestigious Miss Universe title, marking significant milestones.

Both Omar and Callingbull etched their names in the history books during the 2024 Miss Universe event. Their participation symbolized a broader representation and inclusivity within the pageant. Credit: Getty Images / Hector Vivas

As the pageant continues to break new ground, 2025 introduces Nadeen Ayoub, making history as the first Miss Palestine.

The backdrop to Ayoub’s participation is a region scarred by conflict. Over two years of intense conflict between Israel and Hamas have left Gaza in ruins. Palestinian health authorities report that since October 7, the Israeli offensive has resulted in at least 68,000 Palestinian casualties. The initial Hamas attack claimed 1,200 lives, including around 30 children, with over 200 individuals taken hostage, according to the Israeli government.

Her first major outing as Miss Palestine was at the 2022 Miss Earth contest, where she placed in the final five. She was then supposed to compete in Miss Universe, but postponed her debut because of the war in Gaza.

In 2022, Ayoub represented Palestine in the Miss Earth competition, which is one of the ‘big four’ international pageants alongside Miss Universe, Miss World, and Miss International. She is pictured here with Miss Earth-Fire, Andrea Aguilera of Colombia, Miss Earth 2012 Mina Sue Choi of South Korea, and Miss Earth-Air Sheridan Mortlock of Australia. Credit: AAP / EPA / Francis R. Malasig

For Ayoub, representing her homeland as Miss Palestine is a significant responsibility.

Ultimately, she would like to see “Palestine thriving” and for Palestinians be able to “to grow, to develop our country”.

Despite this, it — and beauty pageants more broadly — remain controversial.

The complex relationship between beauty pageants and politics

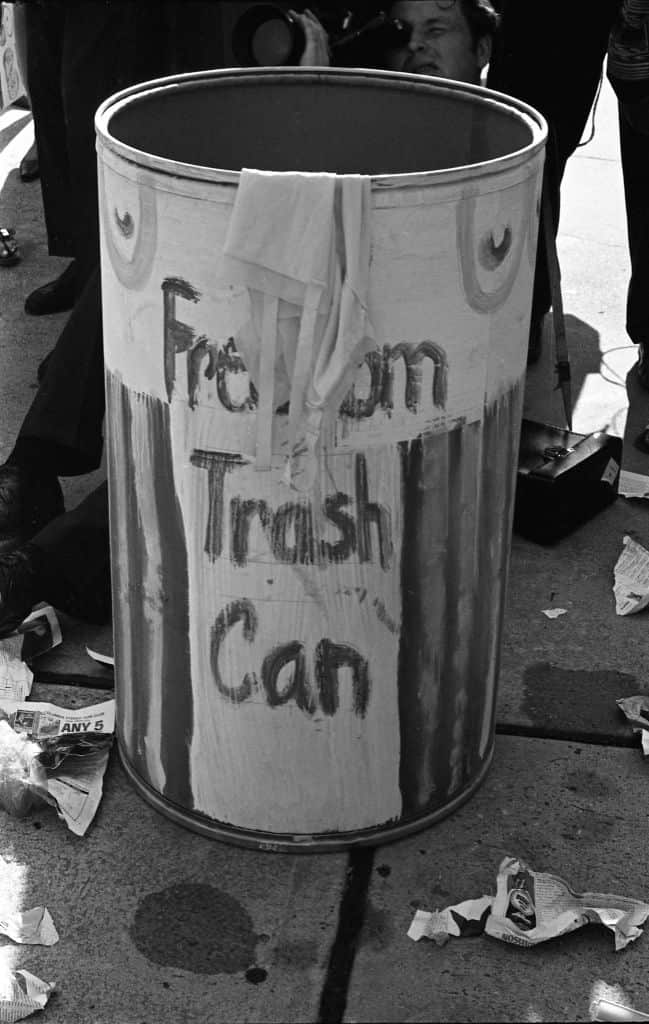

“This is where the myth of the feminist bra burning comes from,” McCann said.

The protest of the 1968 Miss America pageant was organised by the New York Radical Women group. Credit: Bev Grant / Getty Images

This early protest was focused more on the contestants than the organisers of the pageant.

“That obviously is a problem with some modes of feminism, which kind of target women rather than the structures.”

Protesters held signs comparing the Miss America pageant to a cattle auction, and paraded sheep. Credit: AAP / AP

The 1996 Miss World pageant in Bengaluru, India, attracted protests from all sides of politics. At the time, the Los Angeles Times reported the contest “brought together modern feminists and turn-back-the-clock Hindu nationalists, left-wing students and right-wing politicians”.

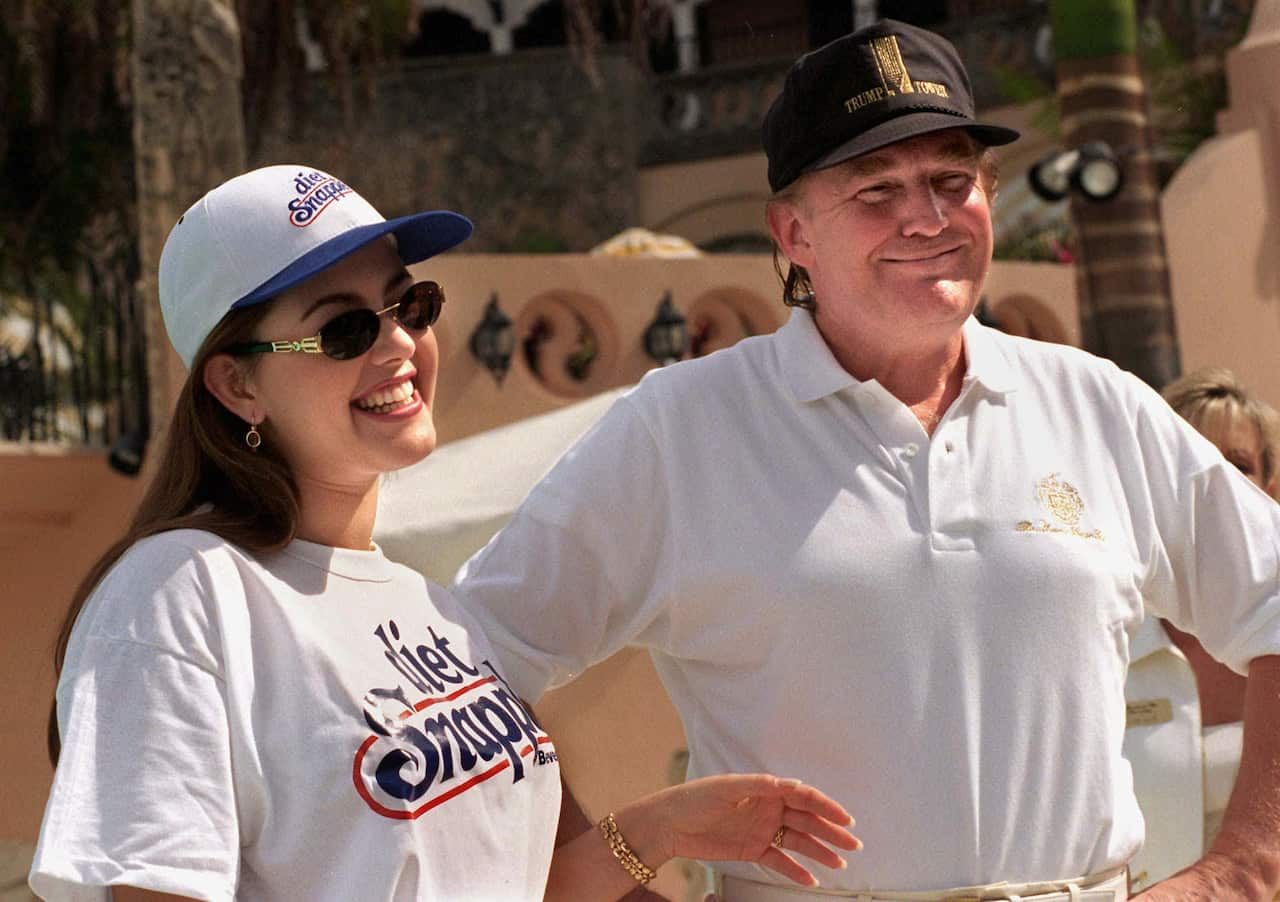

For the Miss Universe contest, a consistent source of criticism between 1996 and 2015 was now-US President Donald Trump’s ownership of the pageant.

Donald Trump inn 2005 with Allie LaForce, Miss Teen USA 2005, Natalie Glebova, Miss Universe 2005, and Chelsea Cooley, Miss USA 2005. Credit: Getty Images / Carley Margolis / FilmMagic

Miss Venezuela Alicia Machado, who won the 1996 competition, said Trump publicly shamed her about gaining weight, including blindsiding her with press and cameras on a trip to the gym that he organised.

He reportedly called her ‘Miss Piggy’ and ‘Miss Housekeeping’, the latter a derogatory reference to her Latina background. Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton brought up his comments during the 2016 presidential campaign debate.

Miss Universe 1996 Alicia Machado said then-Miss Universe owner Donald Trump made critical comments about her weight. Credit: AAP / AP / Lannis Waters / The Palm Beach Post

Trump sold Miss Universe in 2015 to the New York-based IMG Worldwide. In 2022, it was bought by Thai company JKN Global Group for US$20 million ($30 million), making its CEO, Anne Jakapong Jakrajutatip, the first transgender woman to own the competition.

How Miss Universe has changed over the years

Her other organisation, Olive Green Academy, is a “sustainability, content creation and AI-focused agency”, according to its website.

In 2018, the pageant’s first transgender entrant, Miss Spain’s Angela Ponce, competed. However, the competition requires trans contestants to have had gender-affirming surgery. One 2019 article in The Independent was headlined ‘All hail Miss Universe, where cis and trans women can be degraded in bikinis on the world stage equally’.

In 2012, Miss Universe changed its rules to allow transgender women to compete. Spain’s Angela Ponce was the first openly trans contestant. Credit: AAP / EPA / Rungroj Yongrit

McCann said a key issue is the fact that pageants are run for profit by a corporation.

The issue is not “parading” or “revealing” the body, but the “labour that’s exploited” to make money for a global corporation. According to Growjo, a website that tracks private companies and startups, Miss Universe has an annual revenue of approximately US$93 million ($143 million).

McCann added that she would “never have a critique of the women who participate”, but of the structure that is “by its very nature extracting something from them”.

National identity and the ‘Olympics of beauty’

“So that has all kinds of ramifications for the fact that this Australia is summarised in the body of this thin, white, very normatively beautiful woman, who then is in all of our advertising campaigns and so on.”

A majority of United Nations member states now recognise the State of Palestine. That includes Australia, which recognised a Palestinian state in September, alongside the UK and Canada. The US and Israel both remain opposed to recognition.

“They can see Palestine from a different perspective.”