Share and Follow

In a contentious 2020 election, Alexander Lukashenko claimed victory for a sixth term as President of Belarus, securing over 80 percent of the vote. However, these results have been hotly disputed by both opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya’s camp and independent observers.

President Lukashenko, a staunch ally of Russian President Vladimir Putin, has been a vocal supporter of Russia’s military actions in Ukraine, further solidifying the ties between the two nations. His allegiance to Putin underscores the geopolitical dynamics in the region.

Following the election, Tsikhanouskaya was forced to flee Belarus under pressure from security forces. She sought refuge in Lithuania, where she has since been tirelessly advocating for political prisoners and rallying support for the Belarusian people. Her efforts also include building international alliances to bolster her cause.

Although Australian political leaders have criticized the legitimacy of the 2020 Belarusian election and shown support for Tsikhanouskaya, Australia’s foreign policy remains focused on recognizing states, rather than individual governments. This stance reflects a diplomatic balancing act in international relations.

Tsikhanouskaya has often spoken about her husband, who was arrested for his activism. “He traveled the country asking people about their lives,” she recalled. “The answers he received exposed the rampant corruption, injustice, and fear. For simply listening to the people, my husband was detained.”

“I got a phone call saying, ‘You’d better stop doing that, or else you will be arrested and your children will go to an orphanage, since both of their parents will be behind bars,’” she told The New Yorker in a December 2020 article.

In 2020, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya and her campaign team “travelled across Belarus speaking about change, dignity, democracy and truth — and to our surprise, millions of Belarusians stood with us,” she said during her November visit to Melbourne. Source: Getty / Thierry Monasse

Tsikhanouskaya said Lukashenko allowed her to run as he didn’t think a woman would be a viable candidate for president.

Belarus was quickly swept by the largest protests in its modern history — and a violent government crackdown.

The white-red-white flag is a widely used symbol of opposition to the Lukashenko regime. It was adopted as Belarus’ official flag when the nation gained independence in 1991, but was replaced in 1995 with one closely resembling that used during the Soviet era. Source: AP / .

Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch estimated that hundreds of thousands of Belarusians took to the streets at the peak of the demonstrations.

The United Nations documented thousands of cases of torture and ill-treatment, and at least four deaths linked to the state’s use of force against protesters.

A 2023 UN Human Rights Council report found an “excessive use of force by law enforcement personnel that was not strictly necessary to protect life or prevent serious injury from an imminent threat” during the 2020 uprising. Source: AAP / EPA / STR

Following the election, Tsikhanouskaya was detained for seven hours at Belarus’ election authority headquarters, where she’d gone to formally challenge the announced results.

For the almost four years her husband was in detention, Tsikhanouskaya was often kept in the dark about his whereabouts.

Siarhei Tsikhanouski, holding a picture of himself before his imprisonment, was sentenced to 18 years in a high-security prison — one of the harshest penalties issued in Belarus’ post-election crackdown. Source: Supplied / Office of Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya

Tsikhanouski was released on 21 June 2025, one of 14 political prisoners pardoned under a US-brokered deal involving a loosening of sanctions on Belarus.

Repression, Russia and the war in Ukraine

In 2023, Tsikhanouskaya was tried in absentia in Belarus and sentenced to 15 years for treason, inciting social hatred and attempting to seize power through bodies like the Coordination Council.

“Sometimes it feels like Belarus is stuck in time. Where else can you find McDonald’s right next to the KGB with a prison for political hostages, or modern Teslas parking near Soviet-time Lenin monuments?” Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya said at her Melbourne event. Source: Getty / Bloomberg

“15 years of prison. This is how the regime ‘rewarded’ my work for democratic changes in Belarus,” Tsikhanouskaya wrote in a social media post at the time.

“Simply accessing information not funded by Russian propaganda has become a form of digital activism,” she said.

“Russian media dominate Belarusian television, newspapers and online spaces, with many bloggers pro-Russian or directly funded by Russian propaganda,” according to Belarusian writer and activist Tony Lashden. Source: Supplied

Reporters Without Borders refers to Belarus as “Europe’s most dangerous country for journalists until Russia’s invasion of Ukraine”, saying the country “continues its massive repression of independent media outlets”.

While Lukashenko has vowed to commit no Belarusian troops to the conflict, he confirmed in December that Russia’s nuclear-capable ‘Oreshnik’ ballistic missile system had been deployed to Belarus and entered active combat duty.

The Russian Defence Ministry released video footage in late December showing the country’s Oreshnik missile system in Belarus. Source: AAP / Russian Defence Ministry / EPA

In an interview with SBS Russian in November, Tsikhanouskaya said Lukashenko’s alignment with the Russian government does not reflect the will of Belarusians.

“Any act of solidarity can lead to five, 10 or 15 years in prison,” she said.

“Belarusian resistance, the Belarusian democratic movement, is not only political diplomacy abroad; it is the daily work of courageous people inside the country, because they form the backbone of our resistance,” Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya told SBS Russian. Source: AFP / John Thys

British think tank Chatham House polled 833 voting-age Belarusians inside the country in December 2024, finding nearly a third of those surveyed supported Russia’s war against Ukraine, while 40 per cent did not.

“Recognise these elections or not: It’s a matter of taste. I don’t care about it. The main thing for me is that Belarusians recognise these elections,” Lukashenko said in response, as reported by Radio Free Europe.

Official state polls, viewed as unreliable by outside observers, routinely report overwhelming trust in Lukashenko and satisfaction with recent election outcomes.

Building a government in exile

“Despite Australia being so far away, I saw a genuinely strong interest in our visit,” Tsikhanouskaya told SBS Russian a week after returning to Europe.

Foreign Minister Penny Wong called Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya “a fearless advocate for democracy and justice” and said her visit was “an important reminder to Australians of the situation in Belarus”. Source: AAP / Mick Tsikas

During the visit, Wong issued a statement condemning “the Lukashenko regime’s human rights violations in Belarus and its continued denial of the civil and political rights of the Belarusian people”.

“We would be very glad to see Australian representatives at the next gathering of the For a Democratic Belarus parliamentary groups in London next year.”

‘We want no Belarusian to remain invisible’

“Consulates have stopped helping Belarusians abroad with any legal procedures … Their passports simply expired — and going back to Belarus means a real risk of being jailed,” Kavalchuk said.

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya told SBS Russian deeper engagement from countries like Australia could make a meaningful difference to the Belarusian democratic movement. Source: SBS News / Zacharias Szumer

The problem is particularly acute given the number of Belarusians who have fled the country since 2020 — although precise figures remain uncertain.

In her interview with SBS Russian, Tsikhanouskaya warned the situation could soon escalate into what she described as a “humanitarian catastrophe”, saying “at least half a million Belarusians who were forced to leave and cannot return will effectively be left without a country — without citizenship”.

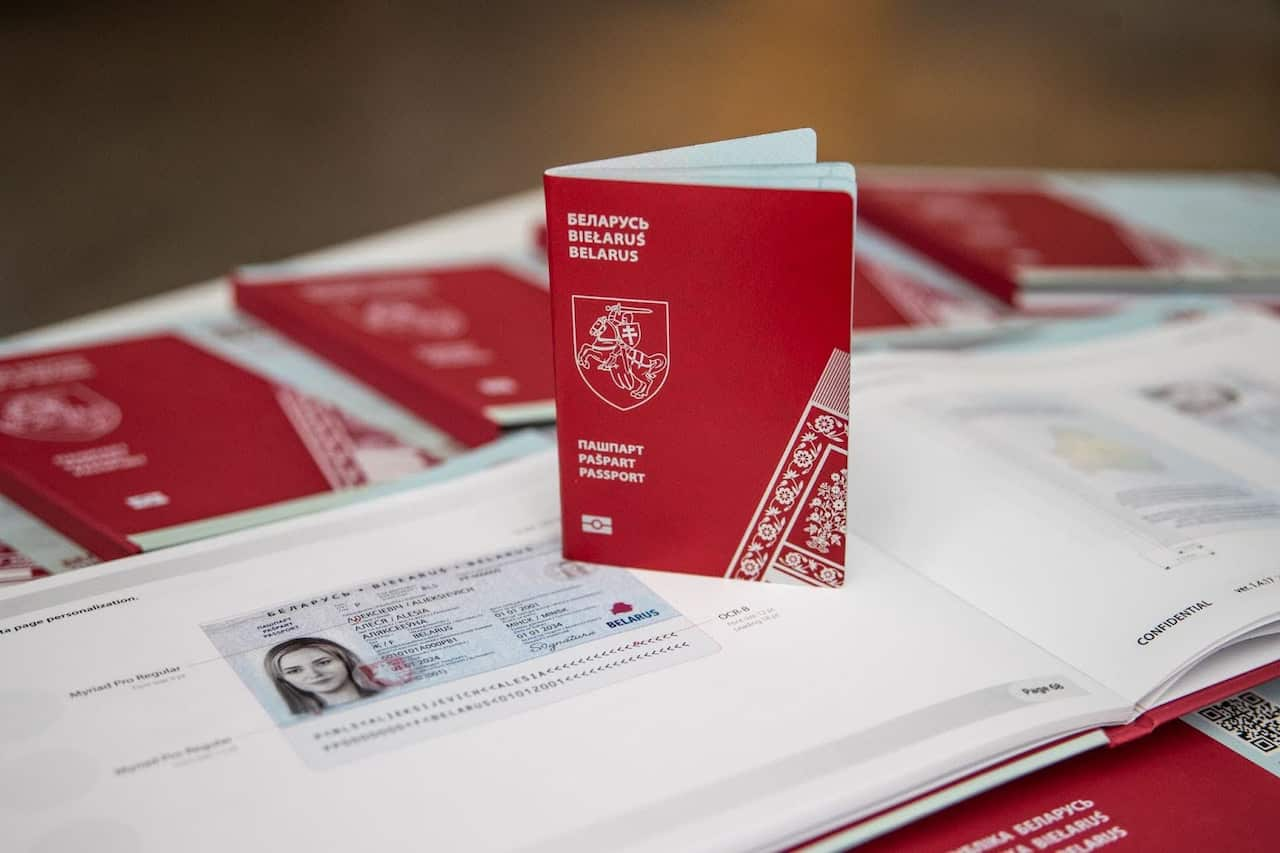

The first biometric passports have been issued and the group is negotiating for their international recognition.

“For thousands of people, it is not just a piece of paper. It is a symbol of belonging to a free Belarus … and shows the regime that we do not have to depend on it,” Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya said of the ‘New Belarus Passports’. Source: Supplied / Office of Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya

Tsikhanouskaya told SBS Russian that, “at the moment, it is more of a symbolic document”, but hopes it will gain formal recognition.

Kavalchuk called the initiative “a good idea” but said it is not yet widely functional: “In Australia, the US and even parts of Europe, it’s not enough to open a bank account or maintain residency.”

‘History is not written by dictators’

Her team is preparing for “a window of opportunity … when Lukashenko is weak enough to get rid of him”, including outreach to officials, elites and military figures.

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya said her husband’s release “gave a huge boost of energy for our movement”, and he has continued to campaign alongside her. Source: Getty / Volha Shukaila / SOPA Images / LightRocket

If Russia emerges stronger from the war, Tsikhanouskaya’s struggle will be harder. But she still hopes her family will one day return to the country of her birth, perhaps entering with a ‘New Belarus Passport’.