If you’re in southeast Queensland, brace yourself.

as a Category 2 storm. The last tropical cyclone to make landfall in region was ex-Tropical Cyclone Zoe in 1974, half a century ago.

Category 2 cyclones produce winds at levels considered damaging at best, destructive at worst — typically bringing gusts as high as 164 kilometres per hour. Minor damage to houses can occur, alongside significant damage to signs, trees and caravans. Power failures are common, while small boats can break moorings. Significant beach erosion is likely on the Sunshine and Gold Coasts.

Cyclone Alfred formed in the Coral Sea 900 kilometres northeast of Cairns nine days ago and headed out to sea. Then it tracked south, reaching severe Category 4 status east of Mackay. In recent days, the storm weakened further as it meandered into the cooler waters of the southern Coral Sea. The cyclone seemed set to peter out, far offshore.

No longer. The latest forecasts show the storm sharply changing direction and making a beeline for heavily populated areas of southeast Queensland.

Its erratic path is not unexpected. The cyclones forming over the Coral Sea have the most unpredictable paths in the world, causing frustration to coastal Queensland residents, fishers, tourist operators and meteorologists themselves. Alfred is a typically unpredictable Coral Sea cyclone. What’s unusual is the fact it has maintained its cyclonic structure and intensity much further south, into subtropical latitudes.

Cyclones, typhoons and hurricanes explained

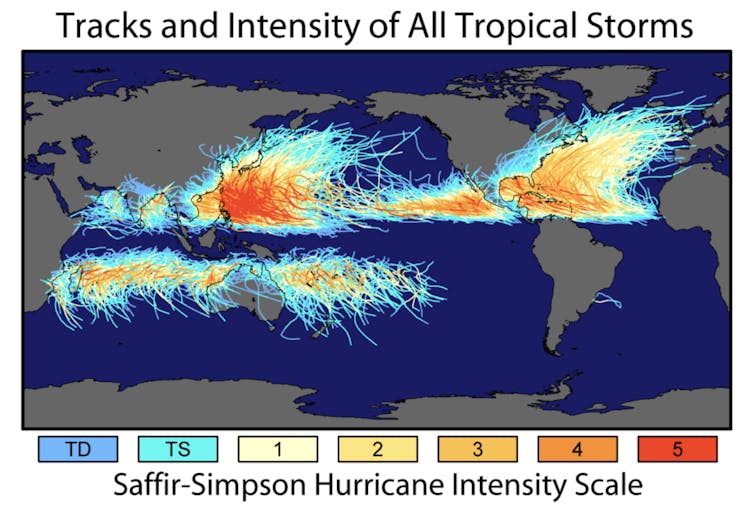

Cyclones, hurricanes and typhoons are different names for the same intense, horizontally rotating tropical storms. They occur in seven tropical ocean basins, above and below the equator.

These storms need atmospheric heat. They can only form over seas warmer than 27°C, where evaporation rates are high. They don’t occur in the cooler South Atlantic basin, and only rarely in the southeast Pacific, when sea surface temperatures are warmer.

The northwest Pacific — off eastern Asia and the Philippines — experiences the world’s most frequent and intense tropical storms (known there as typhoons).

Australia averages about 13 cyclones a year. Most won’t make landfall and only a few are severe. By contrast, the world’s hardest hit nation is China, where six cyclones make landfall annually, followed by the Philippines.

This map shows the aggregated paths of the world’s tropical cyclone over the 150 years to 2006. Note: this map uses the Saffir-Simpson scale in measuring wind speeds, which differs slightly to the Australian scale. Source: The Conversation / NASA

In the north Pacific and north Atlantic, cyclones typically follow predictable tracks. They move westwards, steered by sub-tropical high pressure systems to their north.

Cyclone paths are also fairly predictable off the northwest coast of Australia. They typically form over the Timor Sea and drift southwest before shifting south and crossing the coast. Some are severe, as we saw with Category 5 Cyclone Zelia last month.

By contrast, Coral Sea cyclones such as Alfred are much harder to predict.

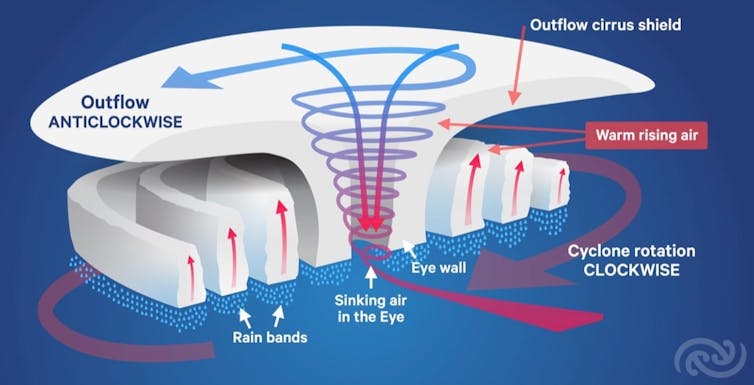

In the southern hemisphere, cyclones spin clockwise. This figure shows how cyclones form around a low pressure system over warm seawater. Depending on their intensity, tropical cyclones are steered by dominant winds in the lower, middle and upper layers of the atmosphere. Source: The Conversation / Metservice New Zealand

How cyclones are steered

Strong winds are the main force steering cyclones, determining direction and forward speed.

Severe tropical cyclones (categories 3–5) are characterised by deep convection currents, which form the famous eye at the centre of the storm, as well as feeder rainbands converging into their centre. Severe systems are generally steered by winds in the middle to upper levels.

By contrast, weaker cyclones (categories 1–2) are much shallower and often have little or no convection around their centre. They tend to be steered by winds in the lower to middle levels. At present, Cyclone Alfred looks to remain relatively weak.

Wind speed and direction can differ markedly in different levels of the atmosphere. Winds can also change direction at the same level. These competing influences are what lies behind the erratic paths of our cyclones.

Cyclones forming in the Coral Sea are more likely to be pushed in different directions by different winds and weather systems than their equivalents in other ocean basins. This is what makes them so hard to predict.

In our region, cyclones are largely steered by two high-pressure systems.

The first pushes cyclones east, and the second steers them west. If both are present and roughly equal in strength, they can hold a cyclone near-stationary. We saw this with Cyclone Alfred for most of the last week.

Slow-moving tropical cyclones such as Alfred are more likely to wander, while faster-moving cyclones such as Severe Cyclone Yasi follow a stronger steering pattern with more predictable paths.

Quite often, cyclones travel south and east out to sea, where they quietly die in a large area of ocean colloquially known as the cyclone graveyard, southeast of Brisbane. These cyclones are steered by different weather systems, upper troughs, cold masses of air from the Southern Ocean.

Cyclone Alfred was initially steered east by a near-equatorial ridge to its northeast, then became stuck between this high-pressure ridge and a sub-tropical ridge to its southwest. This is why it meandered very slowly south and built up strength to become severe. An upper trough then pushed it southeast over the weekend. This week, it’s likely to turn sharply westward towards land, propelled by a high-pressure ridge to the south.

Landfall — but where?

After meandering around the Coral Sea for more than a week, Cyclone Alfred’s forecast track now seems more certain.

The system is expected to intensify from a Category 1 to 2 tomorrow as it moves over warmer waters and draws in more moisture-laden air. This should see it maintain near Category 2 status until landfall. After it hits, it should rapidly weaken to a tropical low over southern Queensland into the weekend.

Alfred will bring a lot of rain, meaning flooded rivers and flash flooding are likely. The Bureau of Meteorology has issued a flood watch for catchments all the way from Maryborough to the Northern Rivers area of New South Wales. These communities should make preparations now.

Cyclone Alfred has a large area of gales, so it will affect a wide swathe of coastline from K’gari (Fraser Island) to Byron Bay. Storm-force winds will cover a 100km wide area, mostly concentrated on its southern flank as it approaches and crosses the coast.

In the longer term, Alfred’s remnants will likely be captured by an approaching upper trough and taken back offshore, where it will quietly die in the cyclone graveyard. Gone but not likely to be forgotten.