Germs could be outpacing modern medicine amid “epidemic levels” of prescribing in Australia, according to new research from the World Health Organization (WHO).

The study released last week shows some of the most harmful pathogens are growing stronger, which experts say may be causing a “vicious cycle” and putting vulnerable groups in harm’s way.

Of particular concern is a group of pathogens typically treated with common antimicrobial medications, which are now showing signs of treatment resistance.

Specialists suggest that the ongoing prescribing patterns might be exacerbating the problem.

Research from the World Health Organization highlights a growing resilience among germs globally, with some areas reporting that a third of infections no longer respond to treatment.

Antimicrobials refer to drugs such as antibiotics, antivirals, antifungals and antiparasitics, which target and kill germs — or pathogens. These are microorganisms that cause disease and include bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites.

Federal health data shows that 50 per cent of Australian hospital patients will receive an antimicrobial, such as broad-spectrum antibiotics, to treat common infections, such as Neisseria gonorrhoeae, which causes gonorrhoea, and Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA), which causes a range of skin infections as well as serious infections like pneumonia and sepsis.

According to data gathered by the WHO from 2018 to 2023, antibiotic resistance has risen annually by 5 to 15 percent.

Data collected by the WHO between 2018 and 2023 shows antibiotic resistance increased between 5 and 15 per cent per annum.

According to its latest survey, one in six laboratory-confirmed bacterial infections causing common infections in people worldwide were found to be resistant to antibiotic treatments in 2023.

Professor Karin Thursky, director of the National Centre for Antimicrobial Stewardship, tells SBS News that while some restricted antimicrobials are prescribed appropriately in Australia, other kinds are being prescribed poorly.

She says Keflex — the brand name for cephalexin — is one of the most prescribed medications in Australia, dispensed for a range of infections including ear, skin, respiratory and urinary tract infections.

It’s given at absolutely epidemic levels.

“At least one in three prescriptions is inappropriate, often because they’re not even needed to be used, particularly for upper respiratory tract or virus infections, or they’re not the right choice,” Thursky says.

Other common antimicrobials, like amoxicillin, are also “exceedingly common” in aged care and hospital settings.

“Those can actually be poorly prescribed, which can lead to poor patient outcomes if they’re not necessary.”

Challenges in some areas

Thursky explains that in an ideal world, doctors would target germs as directly as possible, with antimicrobials that impact a “narrower spectrum”, as opposed to far-reaching broad-spectrum antibiotics.

“There often is a temptation for doctors to reach for a really strong antibiotic when a much narrower spectrum one is okay,” she says, adding that it’s usually recommended that doctors review microbiology results to see if they can reduce treatment to a narrower spectrum antimicrobial.

However, this requires specialist expertise and equipment, both of which can be hard to access in regional and remote parts of Australia.

“You often don’t have microbiology on site, you won’t have stewardship teams [or] even have an on-site pharmacist,” Thursky says.

“They’re relying on relationships with other hospitals to provide those services.”

Prescribing the wrong type or quantity of antimicrobial can have devastating health outcomes for patients — including prolonged sickness or, in some cases, even death.

It can also contribute to a major global health risk: antimicrobial resistance or AMR.

It’s a catch-22 that Dr Trent Yarwood tells SBS News is an “inevitable” evolution in the ongoing battle between medical innovation and ever-changing pathogens.

How do germs become more resistant?

Essentially, AMR occurs when germs are treated with medication and respond through genetic adaptation and multiplication. Over time, this makes them more resistant to treatment.

“Resistance is something that happens inevitably,” says Yarwood, an infectious diseases physician with the Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases.

“You expose the germs to some antibiotics and just by random chance there’ll be one or two that are a bit resistant to that.

“Because you’ve killed off all the ones that are not resistant, then those couple that are left over are able — if you don’t treat the infection completely — [to] multiply and take its place.”

Yarwood says that while antibiotics are “incredibly important” for patients undergoing chemotherapy, intensive care and joint replacements, their use can create a “vicious cycle”.

The more antibiotic you use, the more likely you’re to see resistant germs, which then means you need to use more antibiotics.

This can create problems for wealthy nations, including Australia, with ready access to antimicrobials.

“The concern for us in Australia is that we do actually have quite high rates of antibiotic use compared to other similar countries. So it’s certainly something that we need to watch out for in the future,” Yarwood says.

Which pathogens are on the rise?

The WHO survey tracked eight common bacterial pathogens with data from over 100 countries.

It found that regions with poorer health care had higher rates of AMR, with one in three infections from Southeast Asia being resistant to treatment.

In Africa, the rate of AMR was closer to one in five infections.

“This means that simple infections, which used to be able to be treated with tablets, now need time in hospital and in some cases have no effective treatment at all,” Yarwood says.

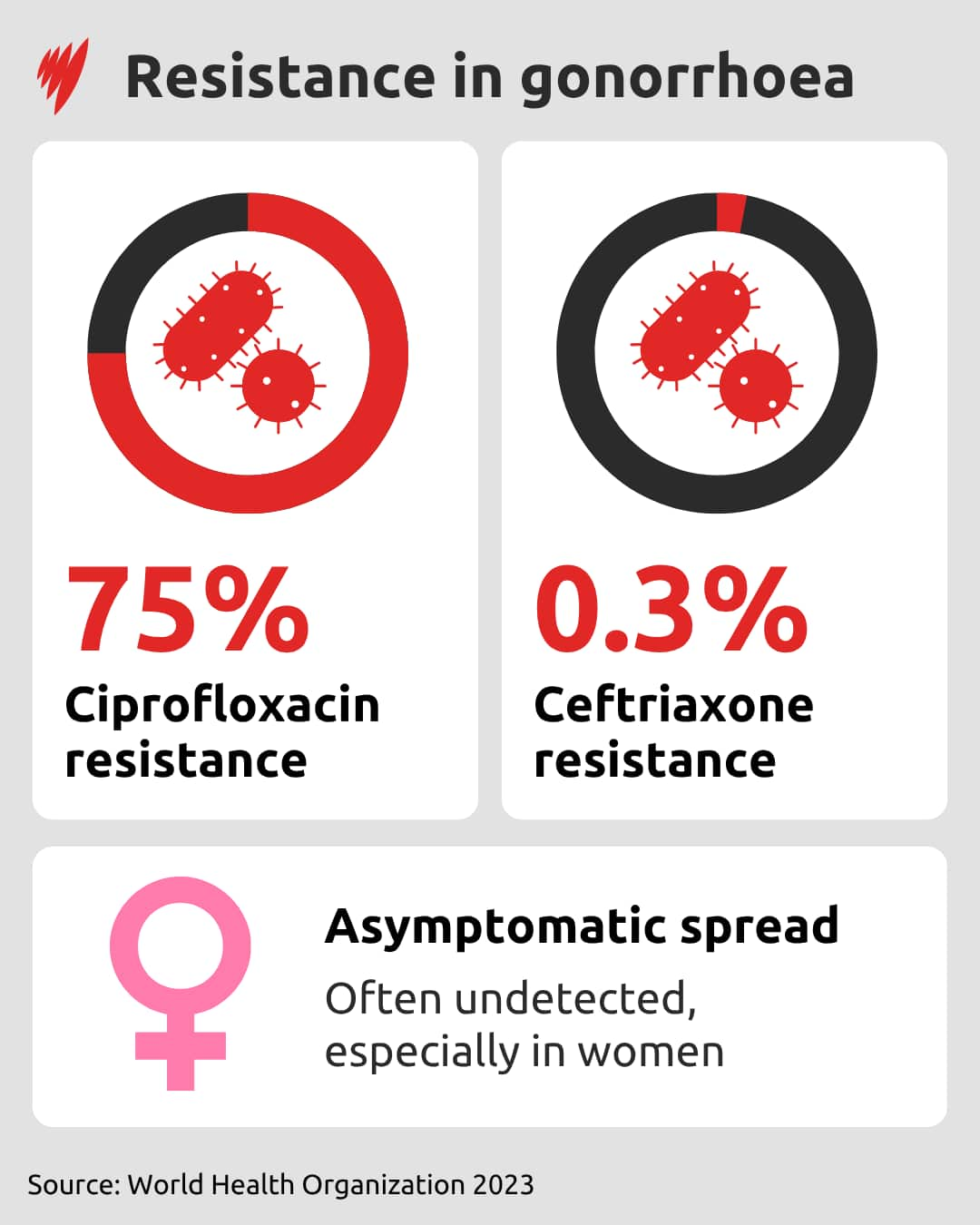

Gonorrhoea is one of the infections that is becoming harder to manage with oral prescriptions, with treatment now often given by injection or in combination with oral tablets.

The WHO survey found that three-quarters of urogenital infections of gonorrhoea were resistant to ciprofloxacin — a broad-spectrum antibiotic — and resistance is growing in the more recently developed medicine ceftriaxone.

Shigella, a pathogen that causes diarrhoea, is also becoming more resistant to oral medicines.

Around 30 per cent of gastrointestinal infections caused by Shigella showed resistance to treatment, increasing the risk of treatment failure.

Some bacteria that can infect the bloodstream are also on the rise around the world.

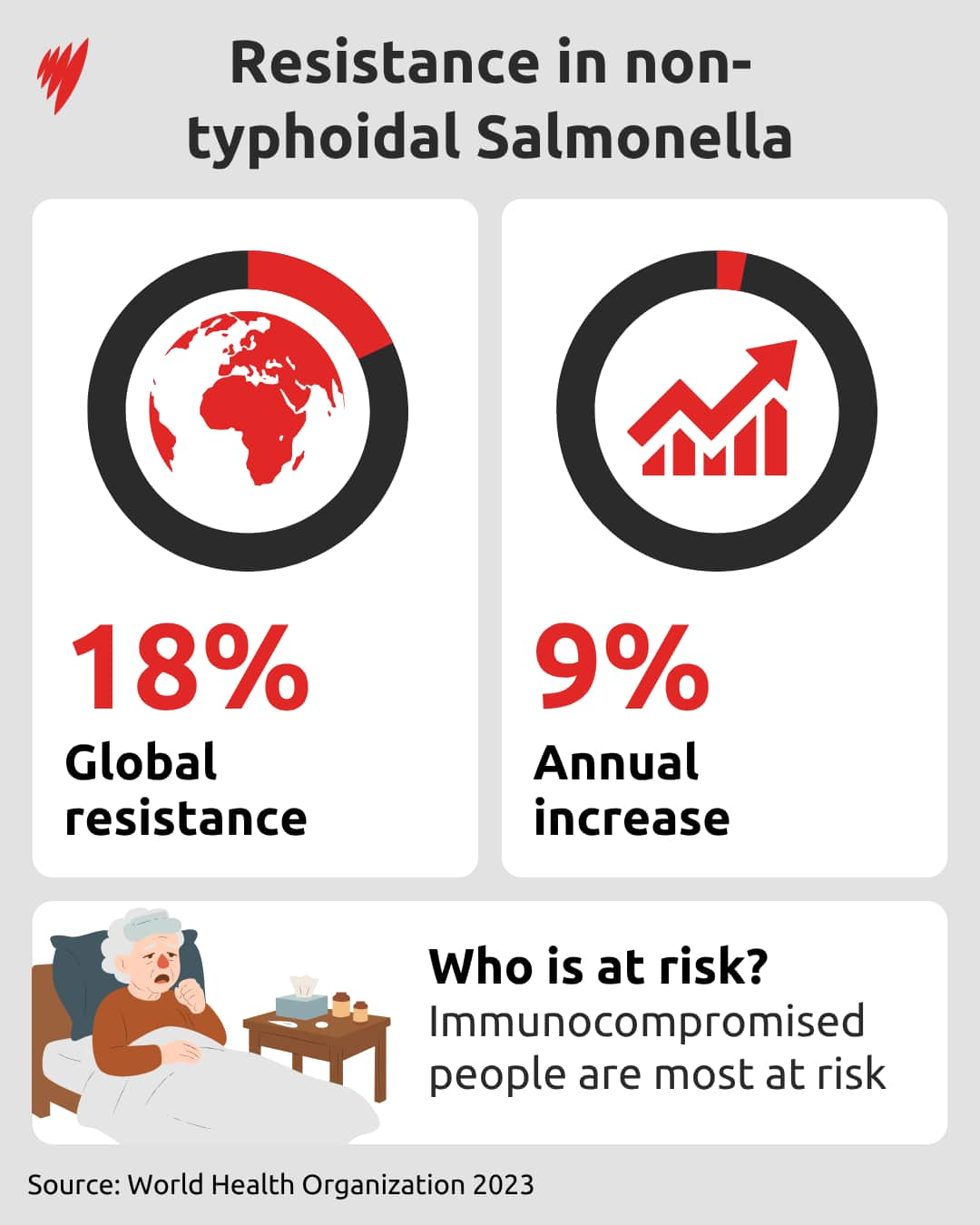

Over the past five years, there has been a 9 per cent annual increase in the number of bloodstream infections stemming from Salmonella, a leading cause of foodborne infection.

Around 18 per cent of these infections are resistant to treatment, with immunocompromised people and those living with HIV identified as the groups most at risk.

For hospital patients and those living in aged care, the threat of MRSA is also becoming a pressing issue.

The bug, which is a kind of staph bacteria, can cause sepsis and is often associated with hospitals, as infection can occur during invasive surgical procedures.

The survey found that 27 per cent of MRSA infections in the bloodstream were resistant to treatment.

A ‘significant risk’ to children

As resistance rises among pathogens, it not only poses a greater risk to immunocompromised people and the elderly, it also heightens the risk for children. Yarwood explains this is due to a rise in the proportion of bacteria in children with an infection becoming resistant to first-line antibiotics.

Anita Williams, a research officer in infectious disease epidemiology at The Kids Research Institute Australia, says the WHO survey findings are “alarming”.

However, she notes Australian children were found to be less vulnerable compared to those from other regions, including Africa and Southeast Asia.

“Globally, 45 per cent of E. coli [bacteria] were resistant to third-generation cephalosporins (a class of broad-spectrum antibiotics). In Australian children, it was only 21.5 per cent,” Williams says.

“For MRSA, globally it was 27.1 per cent, whilst in Australian children it was 13.6 per cent.”

Williams says over the past decade, resistance to first-line antibiotics such as co-trimoxazole (used for a range of bacterial infections) and Augmentin (a type of penicillin) have increased in Australia.

“Since 2013, enterobacterials such as E. coli resistant to co-trimoxazole have increased from 16.9 per cent to 24.8 per cent, and resistance to Augmentin has increased from 4.2 per cent to 12.8 per cent,” she says, referring to the WHO’s findings.

These antibiotics are common first-line treatment for urinary tract infections in children.

Although lower than reported globally, these numbers “represent a significant risk to paediatric healthcare in Australia”, Williams says.

How do we fight antimicrobial resistance?

According to Yarwood, the best ways to fight AMR are to prevent infections in the first place and to have good-quality prescribing.

But he says a key challenge in outpacing ever-evolving germs is the lack of new drug development, as pharmaceutical companies aren’t financially incentivised to research new antibiotics.

“You might put someone on a week’s course of this new antibiotic and then that’s it. So the drug companies aren’t selling a lot of product,” he says.

“Whereas if they find a blood pressure medication or a cholesterol medication or something for some sort of chronic disease, then once you start on that, you’re probably going to be on that for five or 10 years.”

He says this creates a financial disincentive to invest in new antimicrobials, leaving governments to take on more of the responsibility.

“The government could create an incentive payment program to help the drug companies actually overcome these financial barriers for doing new antibiotic research,” he says.

Thursky says antimicrobial stewardship also plays a “vital role” in reducing the risk of AMR.

It involves ensuring the right drug is selected at the right dose, for the right duration, and only when needed.

“Australia has been leading in stewardship programs for a very long time,” she says.

“We have things like antimicrobial stewardship teams, which are typically made up variably by trained pharmacists, infectious disease physicians, microbiologists, and they review any microbial use in hospitals.”

Thursky would like to see more health practitioners, including nurses and pharmacists, able to prescribe antibiotics to ensure everyone, regardless of background, can receive the best care.

“We have major problems with the workforce in Australia, equity of access, rural, regional, remote and communities where there are often non-medical prescribers.

“So there’s definitely a role to accredit nurses and pharmacists, and the main safeguard is that they’ll be overseen by clinicians and stewards to make sure that we can monitor the appropriateness of their prescribing.”