Share and Follow

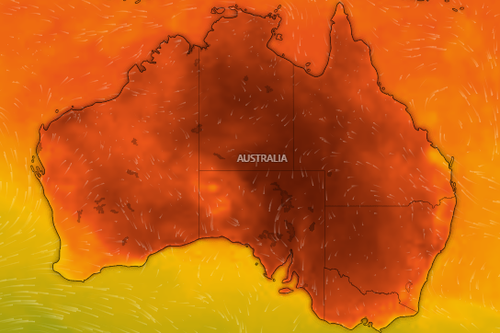

In 2022, Spain pioneered a novel approach by assigning names to heatwaves, setting a global precedent that has since ignited discussions in Australia. The reason for this is clear: in Australia, heatwaves result in more fatalities and hospitalizations annually than any other natural hazard.

Independent MP Monique Ryan has advanced this conversation by proposing an intriguing idea—naming heatwaves after coal and gas companies. Her rationale is that associating these extreme weather events with major contributors to climate change could enhance public awareness and accountability.

“Extreme heat is not only a health crisis but also a failure in communication,” Ryan emphasized. “Every heatwave is a potential mass casualty event; by naming them, we can save Australian lives.”

However, there are varying opinions on this approach. UNSW researcher Samuel Cornell has expressed concern that linking heatwaves to climate polluters might divert the intended public messaging. Yet, he acknowledges the importance of naming these events, as they represent a significant environmental threat, claiming numerous lives each year.

“They are our greatest environmental threat in the sense of the number of lives that they take each year,” he said.

“They’re quite a silent killer. They’re not a very visible natural hazard, unlike things like floods or cyclones.

“If you give something a name, it helps to stick in people’s minds, it helps the media to report on it.”

Australians are used to blistering temperatures, so what’s the fuss all about?

A heatwave is more technical than just a spate of hot days.

The Bureau of Meteorology declares a heatwave when the maximum and minimum temperatures are unusually hot compared to the local climate over three days, and the mercury fails to adequately cool overnight.

These typically come with fire bans, as heatwaves create the perfect environment for bushfires.

In the 10 years to 2022, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare found extreme heat accounted for 293 deaths and 7104 hospitalisations.

Cornell said some people can be unaware that there is a heatwave going on, like the elderly, who have worse thermal regulation and may not feel rising temperatures and take adequate precautions.

But the Bureau of Meteorology said it had no plans to start naming heatwaves.

”This is due to the complex nature of heatwaves,” a spokesperson said, pointing to the differing levels of severity, simultaneous heatwaves and changing conditions.

Others also believe naming heatwaves could be unnecessary.

A UK study in 2025 found naming heatwaves had little effect on the perceived risk and did not encourage people to take safety precautions, while the World Meteorological Organisation found it misdirected public and media attention away from the people in danger.

But Cornell said the matter was still worth exploring as the climate crisis fuels more and more heatwaves.

CSIRO research engineer Dr Annette Stellema said rising temperatures around the world were leading to new heat records.

Just in the past week, a South Australian town and the state of Victoria recorded their hottest days on record.

“Australia’s climate has warmed by an average of 1.51 degrees since national records began in 1910, which has led to an increase in the frequency of extreme heat events,” Stellema said.

“It’s expected that in the coming decades, Australia will experience ongoing changes to its weather and climate, with a continued increase in air temperatures, with more heat extremes.”

NEVER MISS A STORY: Get your breaking news and exclusive stories first by following us across all platforms.