Share and Follow

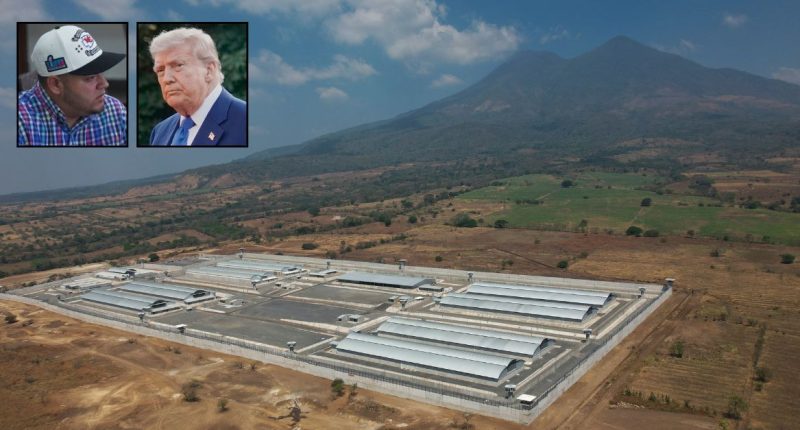

Inset left: Kilmar Abrego Garcia speaks in a hotel restaurant in San Salvador, El Salvador, Thursday, April 17, 2025 (Press Office Sen. Van Hollen, via AP). Inset right: President Donald Trump arrives for a formal dinner at the Paleis Huis ten Bosch in The Hague, Netherlands, Tuesday, June 24, 2025 (AP Photo/Markus Schreiber). Background: A mega-prison known as Detention Center Against Terrorism (CECOT) stands in Tecoluca, El Salvador, March 5, 2023 (AP Photo/Salvador Melendez, File).

Kilmar Abrego Garcia”s time in a notorious Salvadoran terrorist prison was filled with “severe beatings,” “psychological torture,” and dehumanizing conditions, he alleged in his first detailed account of the weeks after his improper deportation from the United States.

The 40-page amended complaint filed in the U.S. District Court for Maryland on Wednesday carries much of the same information and allegations already filed – from Abrego Garcia’s erroneous deportation without due process to El Salvador on March 15 to his request for injunctive relief.

However, while the original March 24 complaint held that he was “at imminent risk of irreparable harm with every additional day he spends detained in CECOT, included but not limited to torture and possible death,” the new complaint maintains some such behavior did indeed happen.

“Plaintiff Abrego Garcia reports that he was subjected to severe mistreatment upon arrival at CECOT, including but not limited to severe beatings, severe sleep deprivation, inadequate nutrition, and psychological torture,” the amended complaint states.

Love true crime? Sign up for our newsletter, The Law&Crime Docket, to get the latest real-life crime stories delivered right to your inbox.

According to the filing, the Maryland man was the first person called to disembark from the deportation plane once it arrived in El Salvador on March 15. After he was placed on a bus in a second set of chains, he was “repeatedly struck by officers when he attempted to raise his head,” the filing continues.

It then describes his arrival at the Central American country’s Terrorism Confinement Center, otherwise known as CECOT.

Upon arrival at CECOT, the detainees were greeted by a prison official who stated, “Welcome to CECOT. Whoever enters here doesn’t leave.” Plaintiff Abrego Garcia was then forced to strip, issued prison clothing, and subjected to physical abuse including being kicked in the legs with boots and struck on his head and arms to make him change clothes faster. His head was shaved with a zero razor, and he was frog-marched to cell 15, being struck with wooden batons along the way. By the following day, Plaintiff Abrego Garcia had visible bruises and lumps all over his body.

The filing continues with startling details.

“In Cell 15, Plaintiff Abrego Garcia and 20 other Salvadorans were forced to kneel from approximately 9:00 PM to 6:00 AM, with guards striking anyone who fell from exhaustion,” his lawyers added. “During this time, Plaintiff Abrego Garcia was denied bathroom access and soiled himself. The detainees were confined to metal bunks with no mattresses in an overcrowded cell with no windows, bright lights that remained on 24 hours a day, and minimal access to sanitation.”

According to Abrego Garcia, after about a week at the maximum security prison, he and the 20 or so other Salvadoran nationals who arrived together were separated based on whether they had clear gang-related tattoos. Twelve men with gang-affiliated markings were placed in another cell, “while Plaintiff Abrego Garcia remained with eight others who, like him, upon information and belief had no gang affiliations or tattoos.”

“As reflected by his segregation, the Salvadoran authorities recognized that Plaintiff Abrego Garcia was not affiliated with any gang and, at around this time, prison officials explicitly acknowledged that Plaintiff Abrego Garcia’s tattoos were not gang-related, telling him ‘your tattoos are fine,'” the filing adds. This description, which was not included in the original complaint, is especially pertinent given that Abrego Garcia’s tattoos became a matter of national attention when President Donald Trump publicly shared a photo of them, claiming them as evidence he was a member of the gang MS-13. Experts and presiding U.S. District Judge Paula Xinis were dubious.

In the July 2 complaint, Abrego Garcia’s lawyers further write that prison officials told him they would move him to the cells containing gang members, “who, they assured him, would ‘tear’ him apart.”

“Indeed, Plaintiff Abrego Garcia repeatedly observed prisoners in nearby cells who he understood to be gang members violently harm each other with no intervention from guards or personnel. Screams from nearby cells would similarly ring out throughout the night without any response from prison guards [or] personnel,” the filing maintains, adding that in his final two weeks at CECOT, Abrego Garcia lost about 31 pounds.

The Maryland man, whose case against the Trump administration has become the symbol of its bumpy deportation efforts, was barred from being deported to El Salvador via an immigration judge’s 2019 withholding order, with the judge finding that he faced a risk of gang persecution. A U.S. Justice Department lawyer later admitted his deportation to the country was due to an “administrative error.”

Still, neither the Trump administration nor Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele – who has touted his CECOT prison’s effectiveness — moved to return the man, even after Xinis ordered the Trump administration to “facilitate” his return and the Supreme Court affirmed this ruling.

Abrego Garcia’s physical status away from the U.S., even after he had been moved to a different prison in El Salvador, seemed at a standstill, until he was suddenly returned to Tennessee in June to face charges related to an alleged “alien smuggling ring.” The charges launched a second case, in which he is now the defendant, which has further complicated matters as to the motivations of both plaintiff and defendant — namely, whether he should be locked up pretrial, in Maryland or Tennessee, and whether DOJ and DHS are on the same page as to what they want to do with him.

Abrego Garcia’s lawyers in this case have decried the smuggling charges as a “farce” and merely an attempt to “convict him in the court of public opinion.” On Thursday, his lawyers reiterated this allegation, asking U.S. District Judge Waverly D. Crenshaw of the Middle District of Tennessee to ban the administration from making “an extrajudicial statement … that … will be disseminated by public communication, and will have a substantial likelihood of materially prejudicing an adjudicative proceeding in the matter.”

Hours later, Crenshaw granted the motion.

The motion for an order of enforcement also traces the background of the case of Abrego Garcia’s summary deportation without due process. In the amended complaint in the Maryland case, his lawyers go a step further than they have previously — alleging that after his detainment, he was lied to about where he was being moved.

According to Abrego Garcia, after being moved to Louisiana under Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) control, he asked to speak with an ICE agent, who “falsely assured Plaintiff Abrego Garcia that he was not being deported to El Salvador but rather was being transported to Texas to appear before a judge. Relying on this misrepresentation, Plaintiff Abrego Garcia cooperated with further transport.”

The Maryland man held that he only learned he was headed to CECOT by overhearing ICE agents conversing, and that this was the first time he discovered “officials had been misleading him about being brought before a judge and that they instead intended to deport him.”

The complaint maintains:

Throughout this entire process, Plaintiff Abrego Garcia continuously informed officials that he possessed legal permission to remain and work in the United States until 2029 and had been granted withholding of removal. He repeatedly requested judicial review. Officials consistently responded with false assurances that he would see a judge, deliberately misleading Plaintiff Abrego Garcia to prevent him from taking actions to assert his legal rights.

A DHS spokeswoman responded to the new complaint in Maryland by targeting the media, saying reporters are “falling all over themselves to defend Kilmar Abrego Garcia.”

“The media’s sympathetic narrative about this criminal illegal gang member has completely fallen apart, yet they continue to peddle his sob story,” the spokeswoman, Tricia McLaughlin, said, per Politico.

Abrego Garcia’s deportation — as well as others — has put a microscope on the topic of due process. While a U.S. district judge in Maryland issued a standing order automatically barring deportations for people who file writs of habeas corpus, the Trump administration has argued that every deportation case needing to be presented in front of a judge would be burdensome and act against the executive interest.

The federal government subsequently sued the U.S. District Court for the District of Maryland and all of its judges over the standing order on habeas petitions.