Share and Follow

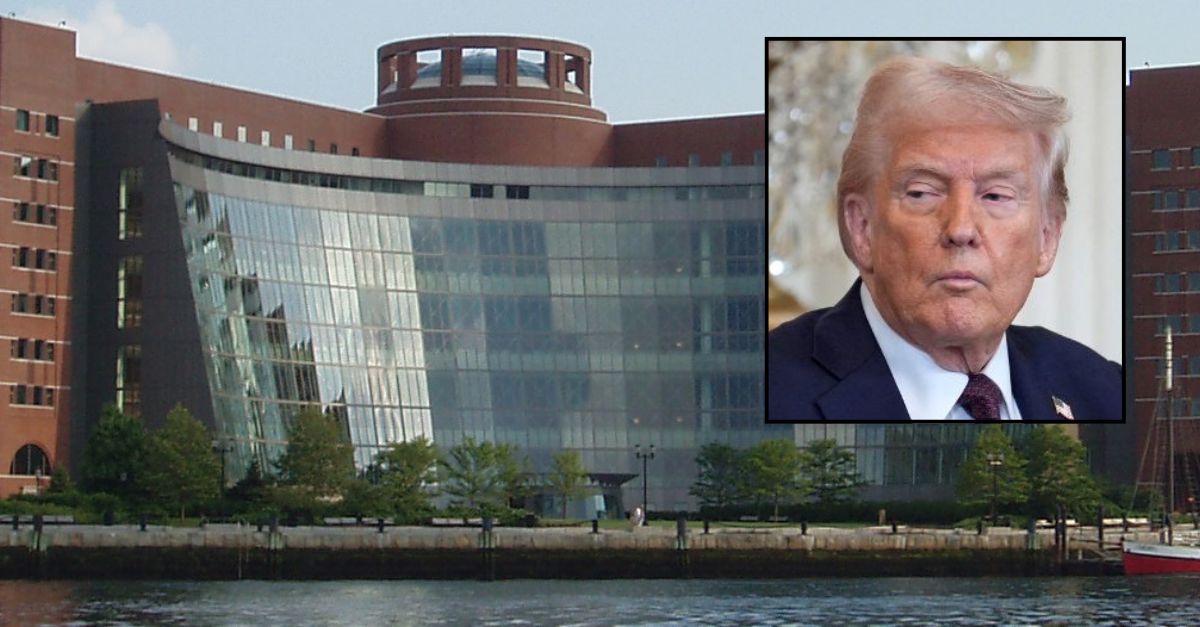

Background: The John J. Moakley Courthouse in Boston, Massachusetts, where the Boston-based 1st U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals meets (U.S. District Court for the District of Massachusetts). Inset: President Donald Trump at a press conference at the White House in Washington on February 27, 2025 (Yuri Gripas/Abaca/Sipa USA; via AP Images).

A federal appeals court has upheld that the Trump administration is not permitted to reduce billions in research grant funding provided by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This decision aligns with a congressional mandate and the Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) own rules, which require the NIH to reimburse “outside entities” based on “actual, documented research costs” rather than providing funds as “lump-sum awards,” according to a recent 38-page ruling from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 1st Circuit.

The legal battle was initiated on February 7, 2025, when the NIH released a “Supplemental Guidance” announcement indicating its intention to limit reimbursement for “indirect costs” linked to NIH-funded research, starting the next business day. This prompted legal action from three distinct plaintiff groups, including 22 state attorneys general, medical associations, and universities.

The opinion, authored by Senior U.S. Circuit Judge Kermit Lipez, explains that recipients of NIH funding can be reimbursed for two types of research expenses: direct and indirect costs. Direct costs are clearly attributable to a specific research project, while indirect costs are more complex.

Indirect costs, also termed “facilities and administration” (F&A) costs, cannot be easily assigned to a single research project. They often include expenses such as equipment upgrades, utility payments, and administrative salaries. The Trump administration’s proposal to cap these “indirect costs” at 15% was seen as an attempt to withhold approximately $4 billion, according to the court’s ruling.

Also known as “facilities and administration” — or F&A — costs, they “cannot be ‘readily and specifically’ attributed to a single research project” and often consist of equipment improvements, utilities payments, and the salaries of administrative personnel. The Trump administration sought to place a cap on the reimbursement of these “indirect costs” at 15%, which, according to the ruling, amounted to a withholding of around $4 billion.

Boston-based U.S. District Judge Angel Kelley essentially said not so fast, issuing a preliminary injunction “barring NIH from taking any steps to implement, apply, or enforce the” new guidance. The preliminary injunction was converted to a permanent injunction, and the guidance was deemed invalid “in its entirety.”

Though the Trump administration would appeal, landing the case before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 1st Circuit, Lipez and the other two judges on the panel found the administration’s arguments unavailing. For one reason, the judges noted, efforts by multiple presidential administrations to put limitations on reimbursements of indirect costs have, “with few exceptions,” failed.

According to the opinion:

One such failed effort is particularly relevant here. In 2017, the first Trump administration issued a budget proposal for 2018 advocating a 10% cap on NIH’s reimbursement of indirect costs. The proposal explained that reducing expenditures on indirect costs would allow “available funding [to] be better targeted toward supporting the highest priority research on diseases that affect human health” and would “bring NIH’s reimbursement rate for indirect costs more in line with the reimbursement rate used by private foundations.” Congress rejected that proposal, with the House Appropriations Committee explaining that it “would have a devastating impact on biomedical research across the country,” and the Senate Appropriations Committee noting that it “would radically change the nature of the [f]ederal [g]overnment’s relationship with the research community” and “jeopardiz[e] biomedical research nationwide.”

Congress went even further and “enacted an appropriations rider ‘directing NIH to continue reimbursing institutions for F&A costs’ and prohibiting NIH from using appropriated funds ‘to implement any further caps on F&A cost reimbursements,’” the opinion says. The Trump administration acknowledged in its 2019 budget proposal that it was indeed prohibited by law “‘from reducing grantee administrative costs and shifting these resources to support direct research’ and urged Congress to ‘eliminate the current prohibition.’”

“Congress declined to do so and instead reenacted the appropriations rider. It has continued to do so in every subsequent year,” the opinion adds, noting that in February 2025 the legislature announced that it would impose “a standard indirect rate of 15% across all NIH grants for indirect costs in lieu of a separately negotiated rate for indirect costs in every grant.”

“Congress went to great lengths to ensure that NIH could not displace negotiated indirect cost reimbursement rates with a uniform rate,” Lipez later wrote.

The opinion added that a sudden uniform cap on indirect costs would go against HHS’ very own regulations that set forth how NIH grant recipients are awarded funding.

The judges held that “NIH’s attempt, through its Supplemental Guidance, to impose a 15% indirect cost reimbursement rate violates the congressionally enacted appropriations rider and HHS’s duly adopted regulations,” Lipez finished by saying. “The district court’s decision is therefore affirmed.”