Share and Follow

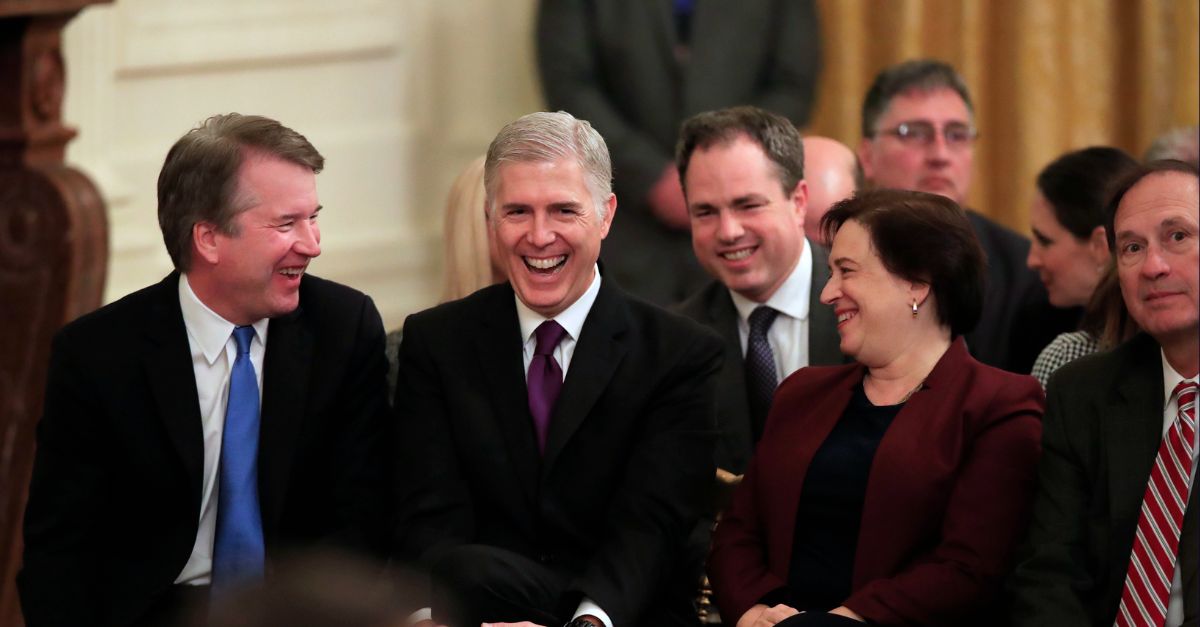

U.S. Supreme Court Justices, left to right, Brett Kavanaugh, Neil Gorsuch, Elena Kagan, and Samuel Alito, talk with other attendees before the start of the presentation of the Presidential Medal of Freedom in the East Room of the White House, in Washington, Friday, Nov. 16, 2018. (AP Photo/Manuel Balce Ceneta)

While not the most headline-grabbing ruling of the day, the U.S. Supreme Court on Wednesday sidestepped a complaint from a business that opposed the storage of spent nuclear fuel or “radioactive waste” at a private facility in Texas, leaving dissenting Justice Neil Gorsuch and two allies wondering how the case had come to this.

At issue was the Nuclear Regulatory Commission”s (NRC) issuance of an “interim storage license” permitting the private company Interim Storage Partners (ISP) to store “thousands of tons of spent nuclear fuel” on property that neither contains a nuclear reactor nor is owned by the federal government, facts that Gorsuch saw as clear proof that the agency “decision was unlawful.”

Although Fasken Land and Minerals and the State of Texas took to federal court to oppose the NRC’s issuance of “a renewable 40-year license,” the challengers failed at the U.S. Supreme Court for a technical reason.

The majority, led by Justice Brett Kavanaugh — and including Chief Justice John Roberts, Justice Sonia Sotomayor, Justice Elena Kagan, Justice Amy Coney Barrett, and Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson — decided that Fasken and Texas were “not entitled to obtain judicial review” because they were “not parties to the Commission’s licensing proceeding” — even though the NRC itself ensured that the private business and “landowner with property near the proposed facility” couldn’t participate in the licensing hearing.

Gorsuch, joined by Justices Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas, began the dissent by decrying the NRC’s heads-I-win, tails-you-lose maneuvering. The justice, in a similar vein to his comments in a recent IRS case, refused to cater to agency gamesmanship.

“The agency’s decision was unlawful,” Gorsuch stated. “Still, the Court says, there is nothing we can do about it.”

“Radioactive waste poses risks to the State, its citizens, its lands, air, and waters, and it poses dangers as well to a neighbor and its employees,” he continued. “But, the Court insists, the agency never admitted Texas or Fasken as ‘parties’ in a hearing it held before issuing ISP’s license — and that’s the rub.”

Gorsuch said that shouldn’t, in fact, be the end of the story because the Nuclear Waste Policy Act is clear about where “radioactive waste” is to be stored — “at reactors or federally owned facilities,” not privately owned land in Andrews County, Texas, with the nearest nuclear reactor “hundreds of miles” away.

“Maybe the agency’s internal rules governing who can participate in its hearing are highly restrictive. Maybe those rules are themselves unlawful. But, the Court reasons, its hands are tied: The agency did not admit Texas or Fasken as parties in its hearing, and that is that,” Gorsuch wrote. “I cannot agree.”

Love true crime? Sign up for our newsletter, The Law&Crime Docket, to get the latest real-life crime stories delivered right to your inbox.

Gorsuch said the NRC should not be able to set itself up to be answerable to no one in pursuit of the “misbegotten license.”

With the majority’s decision, Gorsuch continued, the Supreme Court is “effectively” allowing the NRC to “keep even a neighboring landowner and the very State in which massive amounts of spent nuclear fuel will be stored from being heard in court.”

“Fox meet henhouse,” he remarked.

Warning that there are “obvious and grave risks associated with transporting highly radioactive material across the country and entrusting it to a private company operating on private property,” Gorsuch bristled at the “fantasies” the licensing agency conjured up for the court.

“The NRC’s theory otherwise requires us to ignore the full scope of the agency’s own licensing proceeding. It forces us to reimagine a statute expanding public access to the agency’s administrative proceedings into one restricting access. And it asks us to believe that the very State in which the agency intends to store spent nuclear fuel indefinitely cannot be heard in court to complain about the agency’s plans,” Gorsuch concluded, with the support of Thomas and Alito. “Because nothing in the law requires us to indulge any of those fantasies, I respectfully dissent.”