Share and Follow

The following contains spoilers for Kaiju No. 8, streaming now on Crunchyroll.

Every year, plenty of shonen anime arrive and try to set a name for themselves in this ever-congested genre that brims with highly acclaimed anime. Kaiju No. 8 also faced the monumental task of separating itself from other anime. Since there is not much room to experiment with core themes, it accomplished this brilliantly by turning lead character Hibino Kafka into one of the most relatable and realistic shonen anime protagonists to emerge in years. This recipe for success all boils down to the choice of making Kafka older than the typical shonen anime protagonist, as he grapples with adulthood’s trials and tribulations.

Kafka starts off as an adult man in his 30s, rightfully struggling with his current job and still dreaming about his ideal career that might never come to fruition. He lives with unfulfilled aspirations and adult insecurities that constantly remind him that his prime years have already passed by. This thought process is something that resonates with most adults in this day and age, and watching Kafka continue to chase his objective against all odds feels both natural and uplifting.

Hibino Kafka Breaks the Mold as the Most Unlikely Shonen Anime Hero

The shonen anime genre in the anime/manga industry has always targeted the adolescent boy and young men age group by structuring a story around a hero who hails from a similar generational background. The most popular shonen anime series, such as Naruto, Bleach, or Jujutsu Kaisen, all center on teenage protagonists just beginning to face life’s challenges and growing through them. These heroes are also usually filled with untapped potential and are physically primed for greatness that they are sure to have later in their lives.

Hibino Kafka represents none of those qualities. He is a 32-year-old man who is way past the most potential-rich years of his life, still clinging to the dream of joining the Defense Force even though he tries his best to move on. By the time Kafka met Reno Ichikawa, Kafka had already failed the Defense Force Entrance Exam multiple times and had accepted his fate as a Cleanup worker to a certain degree. He knows that moping about his present won’t change anything, so he throws himself into his thankless job and stays begrudgingly productive.

From here, it gets proven that Kaiju No. 8 is not the story of a prodigy discovering his talent or destiny, but of a normal man who was already told he had lost his chance, yet refused to wholeheartedly give up. When Reno informs Kafka that the age range for recruitment in the Defense Force has been raised to 33, Kafka gets another shot at his goal. This was unexpected yet reflective of real life, where opportunities can arise at any moment, but it ultimately depends on the individual to seize them.

Kafka is also a mirror for many adults who dream big in their teenage years but choose a different path later because of their circumstances. As a hero, he is also refreshing to witness because his heroism grows from persistence rather than raw talent. By deliberately making Kafka physically unassuming and far removed from the typical persona so prevalent in the shonen anime archetype, the narrative makes the audience relate to him. There is no doubt that the spectacle of Kaiju No. 8 is the Kaiju, but at its core, it is Kafka’s story and not the other way round.

There Is a Quarter-Life Crisis at the Heart of Kaiju No 8

In many ways, Kafka’s journey is a living example of a quarter-life crisis, where it is not too late for him to entirely give up, but he is also not young enough to experiment with his career. The reason why his creator, Naoya Matsumoto, managed to portray the hardships of Kafka so convincingly is that this idea of a struggling hero is something that is inspired by his own life.

In an interview with Bunshun, Matsumoto revealed that he himself was in doubt that a character so unlike the stock handsome shonen anime hero would be accepted by others. His apprehension comes alive directly within the manga as Kafka’s peers frequently call him an “old man” and mention his potbelly as friendly jabs. Even Kafka’s age and the aspect of self-doubt were drawn from Matsumoto’s own experiences as a manga artist.

There’s a big part of me projecting myself into the character. At the time, I couldn’t make a living from my manga either, and I was earning a living in a place that was close to my dream but far away. Every time I saw my manga artist friends doing well in magazines, I felt complicated and wondered, “Why am I on this side of the world?” I think that’s when Hibino Kafka was born naturally from within me.

The frustration Matsumoto felt as a mangaka found an expression in Kafka. This parallel becomes unmistakable in the very first chapter of the manga, where Kafka, much like Matsumoto, voices the exact same question, “How’d I wind up on this side of things?” This question does prove his self-doubt, but it also showcases his grounded realization of his current self.

Yet Kafka masterfully resists the cynicism that usually comes with a quarter-life crisis. Throughout the storyline, he is not resentful of others’ success or jealous of Mina Ashiro, who is younger than him, yet succeeds in the very field he also promised to join. When Kafka enters the Third Division, not as a formal troop member but just as a cadet under Vice-Captain Soshiro Hoshina, he is ecstatic to at least get the chance to be part of the team.

While being in his group, Kafka is supportive of the younger, more talented rookies, even when they surpass him. Thus, his age becomes less of a limitation and more of a medium that fills him with patience and a sense of responsibility, reflected in his brotherly care toward others, especially Reno and Kikoru Shinomiya. In a world where monsters run rampant, Kafka really solidifies the idea that growth does not expire with age.

Even Power Doesn’t Spare Kafka from Proving Himself

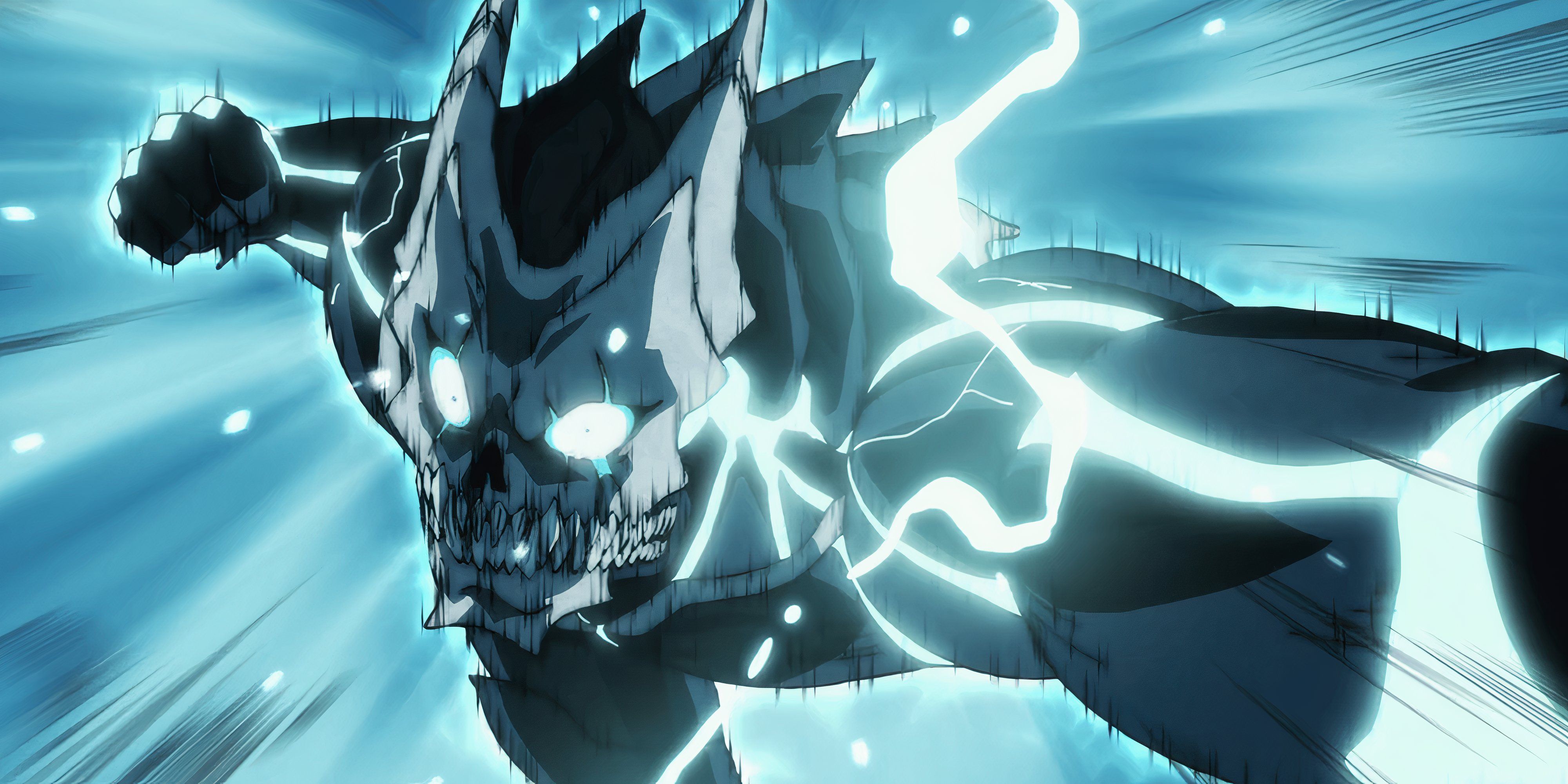

Kafta’s adulthood rut takes on even deeper pathos with the character’s power struggles. In many shonen anime series, gaining power automatically provides a turning point for the protagonist to go ahead of others. However, for Kafka, getting revealed as Kaiju No. 8 was more of a hassle than a boon. It not only made him a public enemy who must be ousted, but also a living target who can be a bigger threat than any Kaiju ever. All his past accomplishments come undone, and he gets the treatment that any monster would, with Isao Shinomiya attacking him to see whether he really can control himself or not.

The Kaiju within Kafka is not at all a silent partner and has a much more volatile presence that can cloud Kafka’s mind, as seen in his fight with Isao. Here, Kafka not only battles Isao, but also the monsters within to get control over his body and reinforce the idea that spiritually he is not the Kaiju No 8 but the human Hibino Kafka. This theme of fighting for his identity reemerges even after his comrades witness his courage and accept him as a part of the Defense Force.

While getting shifted to the First Division, its Captain, Gen Narumi, refuses to take him and only relents when Kafka manages to convince him that he cannot die yet. Needless to say, Kafka earns his place not by going all-out but by proving he can hold back and put others first. In a way, Kaiju No. 8 also flips the script on the concept that being strong is everything. Where the hero himself might become a threat to others, establishing that he deserves to use that strength matters the most. This subversion gels well with Kaiju No 8‘s more seasoned shonen anime protagonist, and ultimately helps make the anime feel even more grounded in reality.

Kafka’s Victory in Kaiju No. 8 Is Personal

Kaiju No. 8 is undoubtedly a rare example of a shonen anime series that speaks to adults tackling struggles far removed from the usual teenage dilemmas. But this series does not completely abandon a younger audience, as their struggles are also shown through a secondary but impactful character like Kikoru.

Kikoru Shinomiya’s journey in Kaiju No. 8 offers an essential look at the pressures faced by youth. Her drive to be the best stems from a desperate need for her father’s acknowledgment, as Isao made her go through years of parental neglect. She becomes an emotional counterpoint to Kafka’s own struggles, showing that the series understands pain across all ages.

In Kaiju No. 8, the monsters are a big part of the franchise and a highlight of the experience, but the story is not about them. Hibino Kafka and, to some extent, other characters become the heart of the story as they live their lives with internal and external battles. Kafka represents the adult dreamer in everyone who still longs to be a hero despite getting to an age where most are told it’s too late.

The biggest reason why Kaiju No. 8 works is because of its universal message that establishes the idea that second chances are not reserved for the chosen ones. Through Matsumoto’s original and Kafka’s fictional journey, Kaiju No 8 proves opportunities do not stop coming, making the series so resonant and Kafka so relatable.