Share and Follow

70,000 square feet of epic street art and graffiti blazes a dynamic and disruptive trail through London’s Saatchi Gallery.

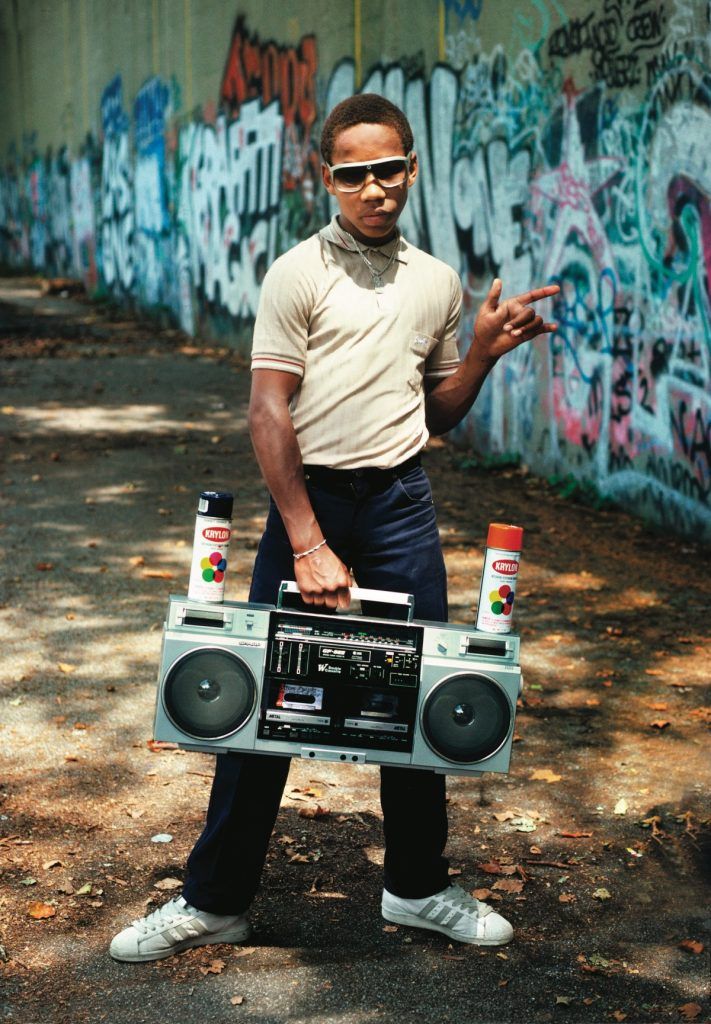

Although the term Street Art was first coined in the late 1970s, the work, by its very nature, is in constant flux and hard to categorise. Broadly speaking, it’s come to define the more visual and engaging urban art as opposed to text-based graffiti and tagging. And anything goes. Common materials and techniques involve fly-posting (also known as wheat-pasting), stencilling, stickers, freehand drawing and videos. It’s almost graphic design. Artists indulge the freedom of working in public without having to worry about what others think (Gordon Matta-Clark, Jenny Holzer and Barbara Kruger all started out in such a way). And graffiti art preceded it, having origins in the very late ’60s and early ’70s in New York, as spray paint became the medium to create images and messages on buildings and the sides of subway trains. Ranging from bright graphic images (wildstyle) to stylised monogram (tag), graffiti was incorporated from street to gallery by the likes of French artist Jean Dubuffet, who suffused his work with graphic motifs and tags. New York artists Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring were street-art pioneers in this respect.

The rise of graffiti and street art

But to fully intuit the rise of graffiti and street art we must go back further, to the advent of video in the late ’50s and early ‘60s, which changed the art world irreparably. Video allowed more freedom and experimentation – and greater portability. And it was perfect for performance art. Video allowed artists to investigate concepts of surveillance; the boundary between public and private. Diane Von Furstenberg once told us Andy Warhol “used to follow me in and out of visits to the toilet with his video camera, documenting everything”. Where sculpture (i.e, a readymade urinal) had allowed Marcel Duchamp to exhibit The Fountain in 1919 and call it “art”, video meant going to the toilet could now be a work of art.

As was its produce. In 1961, Italian artist Piero Manzoni produced 90 cans of his own excrement in numbered editions. The instruction read: “Artist’s Shit, contents: 30g net freshly preserved, produced and tinned in May 1961.” Said Manzoni of his ambitions: “If collectors want something intimate, really personal to the artist, there’s the artist’s own shit, that is really his.”

The creative process was becoming a question of packaging, marketing, branding and re-branding, closely aligned to the broader mechanisms of consumerism and commodification. Video art required viewers to lend their attention in a different manner from a traditional art object. In this way, video art changed the exhibition experience. And with it, artists were soon using technology as sculptural material – think Nam June Paik’s television sets, or Dan Flavin’s use of fluorescent lighting tubes. This was pre-digital disruption 1.0.

That notion of logo and branding was appropriated by American artist Jenny Holzer, who invoked the materials and presentation techniques of advertising, in the form of electronic LED signs, to convey extremely personal, philosophical and sometimes cryptic messages in the form of aphorisms that linger in the mind. “A great feature of the signs is their capacity to move, which I love because it’s so much like the spoken word.” And naturally, there are strong parallels between a graffiti-sprayed name on a moving subway train, or an emotive aphorism on an LED sign. Or even a static one. While Tracey Emin’s neons may not be “street art” per se, they’re still visible in railway stations such as London’s St Pancras, where her I Want My Time With You neon has become as much a part of tourist folklore and IG as Harrods or Tate Modern.

Graffiti’s New York moment

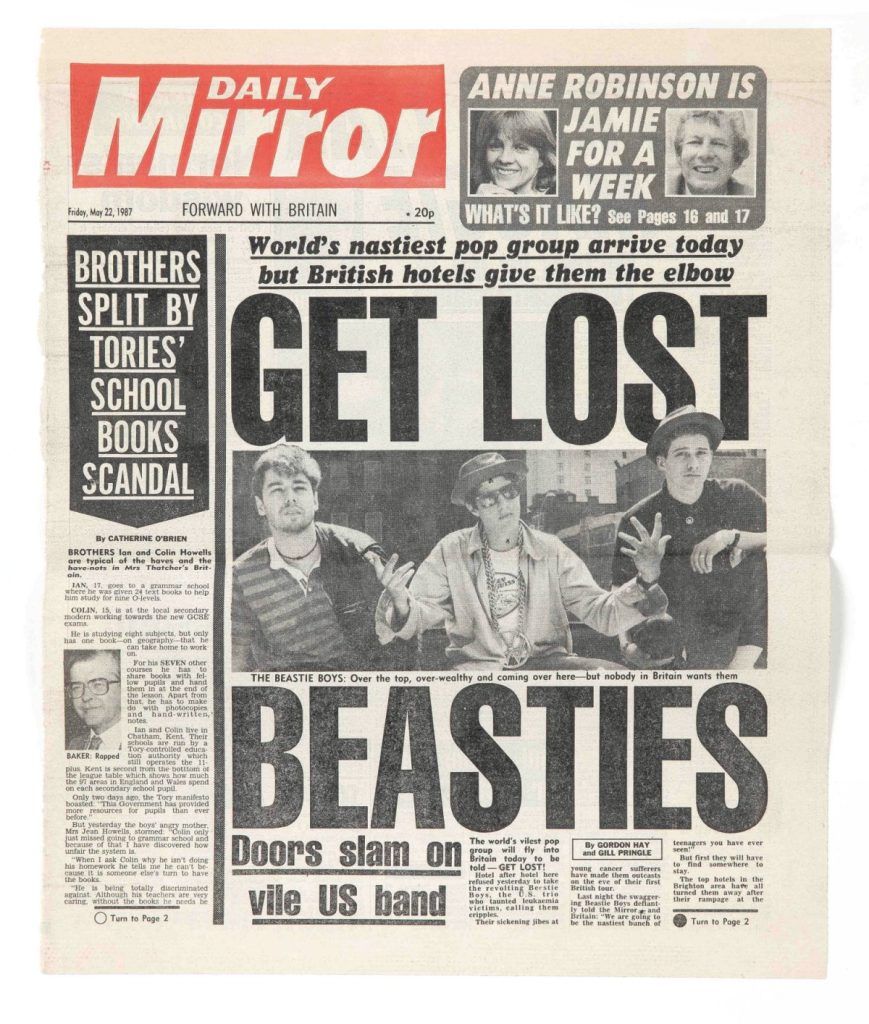

But graffiti’s major moment came in 1974, almost a decade after it had first started in New York. American author Norman Mailer was commissioned by Esquire magazine to write a piece on the phenomenon of graffiti art in New York. Mailer hung out with a bunch of graffiti/ street artists, and noted that, they do not use their own name. They adopt a name. Like a logo. And they admire and worship it. “I sometimes go on Sunday to Seventh Avenue 86 Street station, and just spend the whole day watching my name go by,” artist Super Kool told Mailer. “There ain’t nowhere I go I can’t see it.” One could argue, it was in this, or these moments, that the democratisation of luxury began. Jean-Paul Goude’s famous Esquire cover showed a black artist in a green beret sitting in front of an easel. Instead of a paint palette, which was cast to one side, he was spray-painting the canvas with an aerosol can. The cover line ran: “The Great Art of the ’70s; Norman Mailer reports on graffiti”.

Mailer reported how, Cay liked to use a red marker, Junior blue, with hundreds of masterpieces to their credit. And he identified Junior’s greatest masterpiece in the tunnel where the track descends from 125 Street to 116 Street. There, high on the wall, is JUNIOR 161 in letters six feet high. The artist Junior proudly told him: “You want to get your name in a place where people don’t know how you could do it, how you could get up to there. You got to make them think.” (It’s a mantra adopted by contemporary street artists like Invader, whose admirers trace his pixelated tiles motifs across global cities like a game.) At one point, Mailer asks Cay about the meaning of the names the graffiti artists take. “The name,” Cay says, “is the faith of graffiti.”

Mailer goes on to describe how a communion took place over New York in this “plant growth of names” until every institutional wall, every modern new school, every old slum warehouse, every standard billboard, and the halls of every high-rise, low-rent housing project were covered by a foliage of graffiti which grew seven or eight feet tall, or even twelve feet high in those places where artists had stood on one another. And after all, Mailer asked, how different, really, is Jackson Pollock’s abstract graffiti? Or Matisse’s blue and green Dance, in which “Matisse’s limbs wind on to one another like the ivy-creeper calligraphies of New York graffiti.”

Read Related Also: Billy Joel Postpones Final MSG Concert Due to ‘Viral Infection’

Banksy and other British street artists

Which sounds a lot like 21st-century Shoreditch in East London. And Hoxton. And Brick Lane. And in Britain, no artist has so successfully raised the profile of street art as the anonymous aesthetic provocateur Banksy: two policemen kissing on the side of a pub in Brighton; a street fighter brandishing a Molotov cocktail that’s in fact a bunch of flowers on a wall in Jerusalem; two soldiers looting during Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans; and even recently, seven new works from the conflict in Ukraine. From police brutality to our tech-obsessed contemporary culture, Banksy’s work has proven more popular than formally commissioned works of public art. Some still consider his work “illegal”, since it’s considered a form of vandalism.

Then there’s Bambi (called “the female Banksy”), an anonymous provocateuse who tackles themes of feminism, street violence, political injustice and pop culture with wit and irony. Her street work regales walls in the London boroughs of Islington and Camden, with figures of the late singer Amy Winehouse, Donald Trump, the Royal Family and, most recently in Islington’s Cross Street, portraits of Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky. Which makes us wonder – what’s the greater act of vandalism; spraying New York subway trains in Brooklyn or pub walls in Brighton, or shredding a sold work of art post-auction at Sotheby’s? And if painting walls with spray cans is illegal, then Shoreditch and Hoxton in London, along with Brick Lane, must represent entire ’hoods of vandalism.

Following blockbuster exhibitions in Los Angeles and New York, Beyond The Streets London at the capital’s Saatchi Gallery is curated by Roger Gastman, noted graffiti historian and founder of Beyond the Streets. “The story of graffiti and street art can’t be told without highlighting the significant role London, and the UK in general played in revolutionising these cultures and continuing to spread the word of their existence,” he says.

Beyond The Streets at Saatchi Gallery

While the show was still being prepared when we spoke, Gastman promised “the majority of the work in the show will be new, so we’re thrilled to work directly with so many artists and their studios, to bring together some historical pieces, along with art made specifically for this exhibition. We’ll have an exciting new Trash Records set up, new puppets from Paul Insect and, of course, Kenny Scharf’s Cosmic Cavern. We’re also bringing the vandal’s bedroom back from Todd James, so plenty of unique stuff.”

James’s The Vandal’s Bedroom made its debut at the Los Angeles MOCA in 2011. The graffiti-filled structure overwhelms the viewer with a teenage environment run amok. Part object, part installation, this bedroom-turned-graffiti-battle-station gives glimpses of plans for an imaginary artistic takeover. Bleeding marker drawings form letter styles from the rough and tumble 1980s New York subway era.

London’s Paul Insect makes paintings which peer into an uncertain world filled with masked people armed with unnerving glares. He made a name for himself as one of London’s original street art trailblazers, first in 1996 with his collective, Insect, which created flyers for raves and parties in the East End. He then broke out as an individual artist with his first solo show in 2007. His gallery work takes the form of abstract portraits in distant landscapes, mixing his street aesthetics with bold colours, Pop imagery and puppetry.

Among the hits – more than 160 artists are exhibiting across the Saatchi Gallery’s entire 70,000-square-foot space – there’s a bunch of discoveries to be made. Argentinian-Spanish artist Felipe Pantone, whose work evokes a collision between analogue past and digitised future, and paints dynamic murals on citycapes with names like Chromadynamica and Optichrome; FUTURA and his creation of Pointman, a spaceman-like figure concocted for the cover art of British trip-hop group, Unkle; French artist Invader, one of whose tile mosaic pieces, Space2, which emulates the pixilation of ’70s and ’80s-era video games, resides on the International Space Station, and Kenny Scharf, former roommates with Keith Haring and part of the 1980s East Village Art movement, so-called “father of a feral expression between street and gallery”, who befriended graffiti artists like DAZE and HAZE and created trademark Cosmic Caverns and immersive Day-Glo paintings (artistic director of Dior and Fendi, Kim Jones, channelled Scharf for a fashion collection as recently as 2020). And Haring, who appreciated Dubuffet’s approach to aesthetics, was inspired by New York’s subway graffiti artists to explore the subway system as a venue for showing his own deliberately primitive markings. And Maripol, a designer and art director who documented everyone from Jean-Michel Basquiat and Scharf, to Haring, Deborah Harry and Madonna at Studio 54 with her cameras and recorders, the French student having been drawn to New York by Mailer’s book, The Faith of Graffiti, a follow-up to his article.

There’s also a street-load of music and fashion references to ponder, along with the art. And talk of another show in Shanghai later this year, if logistics allow. Hit those streets people.

(Header image: Optichromie 114 by Argentinian-Spanish artist Felipe Pantone (Photo © FPSTUDIO, 2019))

!function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s)

{if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function(){n.callMethod?

n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments)};

if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version=’2.0′;

n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0;

t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0];

s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)}(window,document,’script’,

‘

fbq(‘init’, ‘2133171443594059’);

fbq(‘track’, ‘PageView’);