Share and Follow

NEW YORK – Capturing moments that echo both today and a century past, the imagery of individuals in custody—at times behind bars or shackled, always under vigilant supervision—remains consistent. These scenes, whether serving as a backdrop or taking center stage, are presented at the discretion of authority figures.

Such visuals have been a defining feature of President Donald Trump’s tenure, reflecting his stringent immigration policies and efforts toward mass deportations. These images have appeared in recruitment ads for Immigration and Customs Enforcement across various cities and in social media content from both the White House and federal agencies.

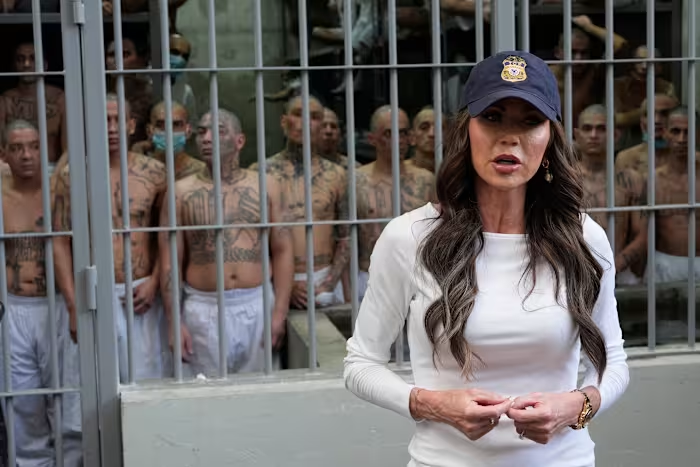

A striking illustration of this came earlier this year when Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem toured a notorious high-security prison in El Salvador. This facility had become a destination for some Venezuelan immigrants under the Trump administration’s directives.

The prison scene was stark: rows of shirtless, tattooed men with shaved heads pressed against the bars of an overcrowded cell, as photographers and videographers captured the moment. Noem, standing before them, issued a warning to immigrants in the United States about the potential for deportation.

The March images sparked a wave of fury and condemnation, criticized by many as a form of propaganda that exacerbates the plight of detainees.

But the playbook is not new.

It goes back almost as far as photography

Such images have been used for more than a century to demonstrate political might and the power of the criminal justice system.

— Photographs of convicted men at work in the sewing room at Alcatraz federal penitentiary in the mid-20th century.

— Images of Black men holding farm tools under the watchful eye of a guard at Mississippi’s oldest prison, Parchman Farm, dating to the early 20th century.

— A 1988 presidential campaign ad created by supporters of Republican candidate George H.W. Bush against Democratic candidate Michael Dukakis, which used the image and criminal history of Willie Horton, a convicted felon, to paint Dukakis as soft on crime.

Showcasing the images of people in detention or the criminal justice system has served multiple purposes over the years, says Ashley Rubin, associate professor of sociology at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. Rubin cited “Wanted” posters and photographs documenting executions.

And some have been about sending a larger message.

“Historically we’ve used images of various kinds, whether it’s actual photographs or paintings, wood types, sketches and that sort of thing, to indicate either the functioning of power or the functioning of a well-ordered state,” Rubin said. She pointed to prison tours organized by authorities to underscore the caliber of the conditions inside, and suspects being brought before the media to showcase a successful law enforcement effort.

But is it ethical?

Visuals are powerful because humans “believe what we see,” at times over the things we are told, said Renita Coleman, who researches visuals and ethics as a journalism professor at the University of Texas at Austin.

“Photographs, we know they work. They get into our brains a different route than … words do. And they get processed faster. They have an emotional component,” she said. “You see a picture, you feel something before you think about it, and that colors everything.”

And an observer’s opinions also can influence how they understand what they’re seeing, Coleman said. With images of detainees, “political ideology is going to affect how people interpret these photographs. To some people, it’s ‘Law and order is a good thing,’ and other people will see people being … used for political messages.”

When detainees are photographed, they generally are not asked if they are willing nor are they in a position to refuse, according to Tara Pixley, assistant professor of journalism at Temple University. Being incarcerated goes hand-in-hand with being considered less than and dehumanized for breaking the law. It’s the officials running things who decide.

But “consent and permission, permission from a person in power and consent from the person being photographed, are two completely different things,” she said.

Politics and prejudice combine

Prejudice and bigotry have gone some way toward making prisoner and criminal justice imagery potent for tough-on-crime rhetoric in electoral politics over the decades, said Ed Chung, vice president of initiatives at the Vera Institute, a criminal justice-focused organization that advocates against mass criminalization.

“Historically, this type of political propaganda has worked to win elections,” he said, citing the ad featuring Willie Horton, a Black man who committed crimes while out of a Massachusetts prison through a furlough program. Dukakis was governor at the time.

Joseph Baker, a professor in the department of sociology and anthropology at East Tennessee State University, says the issues of race and class that run through American society are part of our feelings about those being detained or imprisoned, and how they’re treated.

“There’s a heavy class dimension, but there’s also a racial ethnic dimension to it. That is a big part of why people feel it’s OK. Because we’re punishing these people who don’t look like me or don’t sound like me or any of that stuff and that sort of allows them to think, ‘oh, you know, good, get those bad people out of here,’” Baker said.

Chung’s organization is trying to educate elected officials and the public about the prison system and advocates for the dignity and humanity of incarcerated people. He’s hopeful those efforts have been making some positive inroads in areas like the push for more and better resources for former prisoners returning to their communities, as well as how crime and safety are talked about.

“When you’re able to step back from the political rhetoric,” he said, “that creates change.”

Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.