Share and Follow

TOKYO (BLOOM) — Hearing someone in pain might actually make you hurt more—literally. A new study out of Tokyo University of Science reveals that ultrasonic “stress calls” from mice in pain can trigger brain inflammation and heightened pain sensitivity in nearby mice, even when they’re not physically touched or injured.

The research, published in PLOS ONE, presents a major development in how scientists understand pain, emotional empathy, and stress-related disorders. The implications are wide-reaching—from improving patient care in hospitals to better managing chronic pain conditions that have puzzled clinicians for decades.

“We demonstrate for the first time that ultrasonic vocalizations emitted in response to pain can induce hypersensitivity in other mice,” said Assistant Professor Satoka Kasai, lead author of the study. “This is sound stress—no injury, no direct contact—and yet it triggers pain-like responses.”

Why It Matters to You

For patients, caregivers, and anyone working in high-stress environments—this study suggests that the sounds of suffering around you could physically affect your body, worsening your own pain or undermining recovery. In short, stress is contagious—and now, sound may be one of its main carriers.

What the Researchers Found

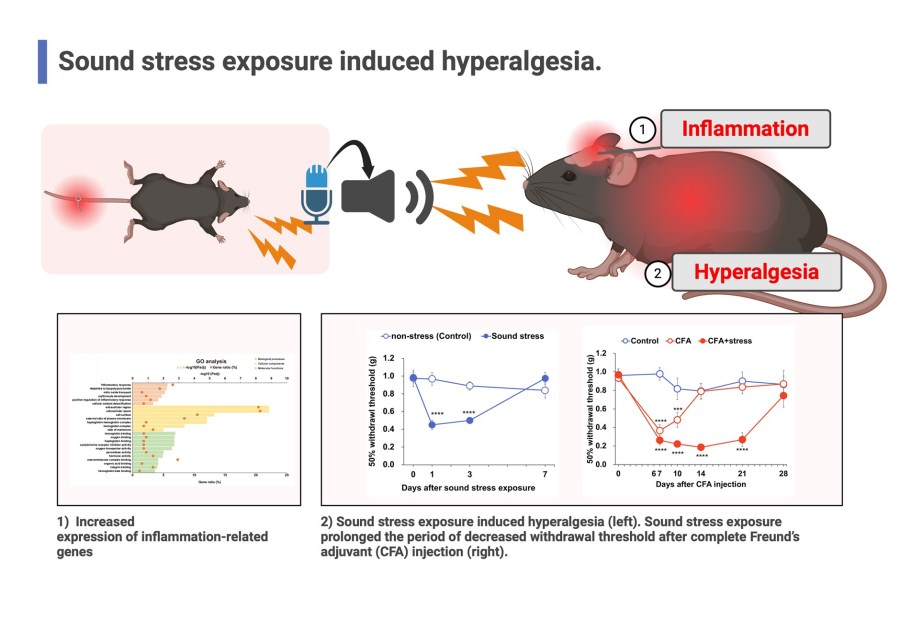

Kasai’s team exposed healthy mice to ultrasonic recordings of other mice in pain. The exposed mice, while uninjured, developed hypersensitivity in their paws, a sign of increased pain perception. Microarray gene analysis revealed that the sound stress activated hundreds of inflammation-related genes in brain tissue.

Key markers like prostaglandin-endoperoxidase synthase 2 and CXCL1, both tied to inflammatory response, were sharply elevated.

Even more striking: when anti-inflammatory drugs were introduced, the pain response was reduced—showing that inflammation directly mediated by sound exposure can be treated.

Beyond the Lab: Sound as a Stressor

The research opens the door for a rethink in how we design medical environments. Hospitals, nursing homes, and even households may benefit from minimizing exposure to distressing sounds—especially for patients already in pain or dealing with chronic illness.

“Soundproofing, calming acoustic design, and mindful auditory environments could be more than just comfort—they could be clinical interventions,” Kasai said.

The findings also hint at why some people seem more sensitive to pain after witnessing others in distress. Emotional empathy, it turns out, may not just be psychological, it could be biological.

What’s Next?

The researchers call for more studies to examine how different types of sound, whether from pain, fear, or sadness, can influence neuroinflammation and pain modulation in the brain. Human trials are still a long way off, but this work lays the foundation for future pain management innovations that go far beyond pharmaceuticals.

The Bottom Line

Sound doesn’t just carry emotion, it can carry pain. Whether in hospital rooms or high-stress homes, paying attention to auditory environments could become a crucial part of better care, mental health support, and pain treatment strategies.

Reference:

Kasai S., Miyazaki S., Saitoh A., Iriyama S.†, Yoshizawa K. Tokyo University of Science. PLOS ONE, 2025. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0324730