Share and Follow

The 1970s produced a trove of films that remain cherished today, marking a period when American cinema transitioned from traditional formulas to the innovative spirit of the New Hollywood era. Globally, cinema was invigorated by various avant-garde movements, making the decade a fertile ground for groundbreaking films that sometimes left audiences bewildered.

Science fiction, in particular, soared during the ’70s, characterized by adventurous narratives and bold experimentation. Although “Star Wars” would not fully cement its influence over Hollywood until the following decade, the ’70s witnessed remarkable technological advancements in filmmaking. This era of innovation, combined with a willingness to explore new ideas, provided a unique opportunity for sci-fi films to break boundaries, blending creativity with cutting-edge techniques.

During this dynamic period, films emerged that defied conventional storytelling, embraced slow pacing and psychological depth, and fused sci-fi with seemingly incompatible genres. Some of these films were immediately celebrated for their visionary qualities, while others initially faced criticism, only to be appreciated by audiences years later. Here, we present a selection of 11 sci-fi movies from the ’70s that were truly ahead of their time, without the use of time travel.

David Lynch’s first feature film, 1977’s “Eraserhead,” represents a landmark in cinematic history, not only for introducing Lynch as a visionary artist but for its sheer audacity. Created while Lynch was at the American Film Institute, “Eraserhead” stands as a profoundly unsettling work of horror surrealism, loosely structured around an enigmatic sci-fi narrative that remains deliberately obscure.

The plot centers on Henry (played by Jack Nance), who resides in a peculiar industrial city afflicted by decay and incessant mechanical noises. Viewers follow Henry as he navigates a tumultuous relationship with his girlfriend Mary (Charlotte Stewart), attempts to win over her parents (Allen Joseph and Jeanne Bates), and contends with a newborn whose unsettling appearance and cries challenge the essence of humanity. The film’s haunting atmosphere is further enhanced by its striking black-and-white cinematography, making “Eraserhead” a modern classic.

Eraserhead

David Lynch’s directorial debut feature, 1977’s “Eraserhead” would already be a turning point in movie history just for having introduced the world to one of the most brilliant artists of all time. But there’s even more to its magnitude. Written, produced, and directed by Lynch while he was a student at the American Film Institute, “Eraserhead” is one of the boldest American films of all time: An uncommercial, limitlessly disturbing exercise in horror surrealism, just barely tethered to a bizarre sci-fi story that never once clarifies its eccentricities.

The story in question follows Henry (Jack Nance), a man who lives in a strange industrial city consumed by decay and constant droning noises. We watch as he navigates his strained relationship with his girlfriend Mary (Charlotte Stewart), struggles fruitlessly to get on the good side of her parents (Allen Joseph and Jeanne Bates), and deals with a newborn baby whose appearance and continuous screams have no recognizable traces of humanity. All of this is given an extra charge of eeriness by “Eraserhead” being one of the great modern movies filmed in black and white.

By dispensing with jump scares and traditional dichotomies between safety and danger, and offering nothing but nonstop nightmare fuel in their stead, Lynch offered an approximation of what “pure horror” might be, untethered from anything but the imperative to be maximally terrifying at every moment. The movie revolutionized student films, set a new benchmark for nauseating sound design, and essentially inaugurated a new strain of surrealism.

Solaris

Andrei Tarkovsky never made a bad movie, but, when he unveiled “Solaris” in 1972, the notion of science fiction as a province of slow, meditative drama was still minimally explored. Even “2001: A Space Odyssey,” released four years prior, had its share of blockbuster thrills; it was nearly unheard-of for a revered arthouse director to use sci-fi elements as a backdrop to strictly personal, inner-conflict-driven storytelling.

Never one to let lack of precedent deter him, Tarkovsky conceived “Solaris” as a serious, thoughtfully-considered adaptation of the eponymous 1961 novel by Polish author Stanisław Lem. The very rejection of sci-fi tropes lies at the core of the movie’s plot: A human-built space station is orbiting the ocean planet Solaris, in an ongoing mission to communicate with the planet or at least understand its functioning. But, instead of making any scientific strides, the station’s crewmates have been left in emotional disarray by an onslaught of strange phenomena. Psychologist Kris Kelvin (Donatas Banionis, with the voice of Vladimir Zamansky) is sent to Solaris to investigate, only to start having visions of his late wife Hari (Natalya Bondarchuk) upon arrival.

Going against all sci-fi convention, Tarkovsky structures “Solaris” as, essentially, a talky chamber drama, in which the painful repressed memories, traumas, and insecurities unearthed in the characters by planet Solaris matter much more than the mission per se. With Tarkovsky having demonstrated that a film in the genre could be that cerebral and psychologically heady, science fiction cinema was never the same again.

Anti-Clock

The British duo of Jane Arden and Jack Bond is among the most visionary filmmaking teams of all time, yet their incredible, seismically original work is still not as widely-known as it ought to be among movie buffs. The last of the three films they made together, 1979’s “Anti-Clock,” is an avant-garde sci-fi masterpiece so unique and inventive that it feels like a dispatch from a parallel dimension.

There is, in fact, a practical reason why “Anti-Clock” bears so little resemblance to anything made after it in the genre. Following a British festival screening and a critically acclaimed theatrical run in the United States, “Anti-Clock” was completely pulled from circulation by Jack Bond in 1983 in the wake of Jane Arden’s suicide. It was not until decades later that the film was made available again, at which time cinephiles were able to discover anew what reviewers in 1979 had already noticed: Here was a work of pure genius.

“Anti-Clock” follows Joseph Sapha (played by Arden’s own son, Sebastian Saville), a suicidal man who agrees to undergo a scientific experiment to dive into his memories and potentially alter them. The means by which Arden and Bond depict Sapha’s mind are stunning to watch even more than four decades later, combining film and video in ways no other director had thought to do before, while also offering shockingly prescient commentary on surveillance, psychological listlessness, and reality’s fickle nature in the information age. It’s mandatory viewing for all fans of out-there cinema.

Fantastic Planet

Animated films don’t get much more envelope-pushing than “Fantastic Planet,” René Laloux’s 1973 sci-fantasy masterpiece about a world in which human beings are the pets. Made with a distinctive style of cutout animation featuring incomparably expressive graphic design from co-writer Roland Topor, this French classic is one of the most beautiful hand-drawn animated films ever; the way it looks and moves alone is so enrapturing that it takes a minute to even register there’s also a story.

By the time said story snaps into focus, however, “Fantastic Planet” also reveals itself as a stunningly mature and thought-provoking work of space fiction. Set in the planet Ygam in the far-away future, “Fantastic Planet” centers around the Draags, a technologically advanced species of giant humanoid blue creatures who live as Ygam’s dominant inhabitants. Their pets of choice are Oms, i.e. humans they’ve brought over from our Earth. But, despite the superficially friendly relationship that some Draags have with “their” Oms, humans live on Ygam as an oppressed, subservient population.

“Fantastic Planet,” which was adapted from the 1957 novel “Oms en série” by Stefan Wul, proceeds to follow the Oms’ efforts to undermine and overthrow the Draags’ tyranny — a story of political resistance that, while highly allegorical and hardly rooted in realism, ultimately goes to surprisingly dark and cogent places. “Fantastic Planet” isn’t interested in working as a straight metaphor for any one specific theme, but it does contain a stunning amount of still-relevant truth about prejudice, dehumanization, and authoritarianism.

Dead Mountaineer’s Hotel

Sometimes translated as “The Dead Mountaineer’s Inn,” “Dead Mountaineer’s Hotel” is a 1970 Soviet novel that broke new literary ground by unceremoniously blending together tropes from detective fiction and sci-fi and thereby wreaking havoc in the established logic of both. In 1979, that novel was adapted to a film that retained the source material’s adventurous spirit, and the result was one of the most sui generis sci-fi movies of all time.

A Soviet-era production from Estonian filmmaker Grigori Kromanov, “Dead Mountaineer’s Hotel” was scripted by the novel’s authors, brothers Arkady and Boris Strugatsky. Latvian actor Uldis Pūcītis stars as Peter Glebsky, a police inspector who follows an anonymous call to the titular remote hotel in the Alps, where he finds that there doesn’t seem to be anything wrong. Then, an avalanche strands him in the Dead Mountaineer’s Hotel along with the other lodgers, at which point strange events begin to occur — including the discovery of a dead body.

Inspector Glebsky sets out to solve the case with limited resources and in claustrophobic proximity with the hotel’s other occupants; eventually, there turns out to be more to them than meets the eye. Kromanov blends sci-fi and film noir in ways that breathe new life into both genres at once, expanding the horizons of what they could accomplish on screen while laying the groundwork for “The Thing”-style paranoia sci-fi in eerie, secluded locations. To this day, there’s very little in the movie world that resembles it.

The Andromeda Strain

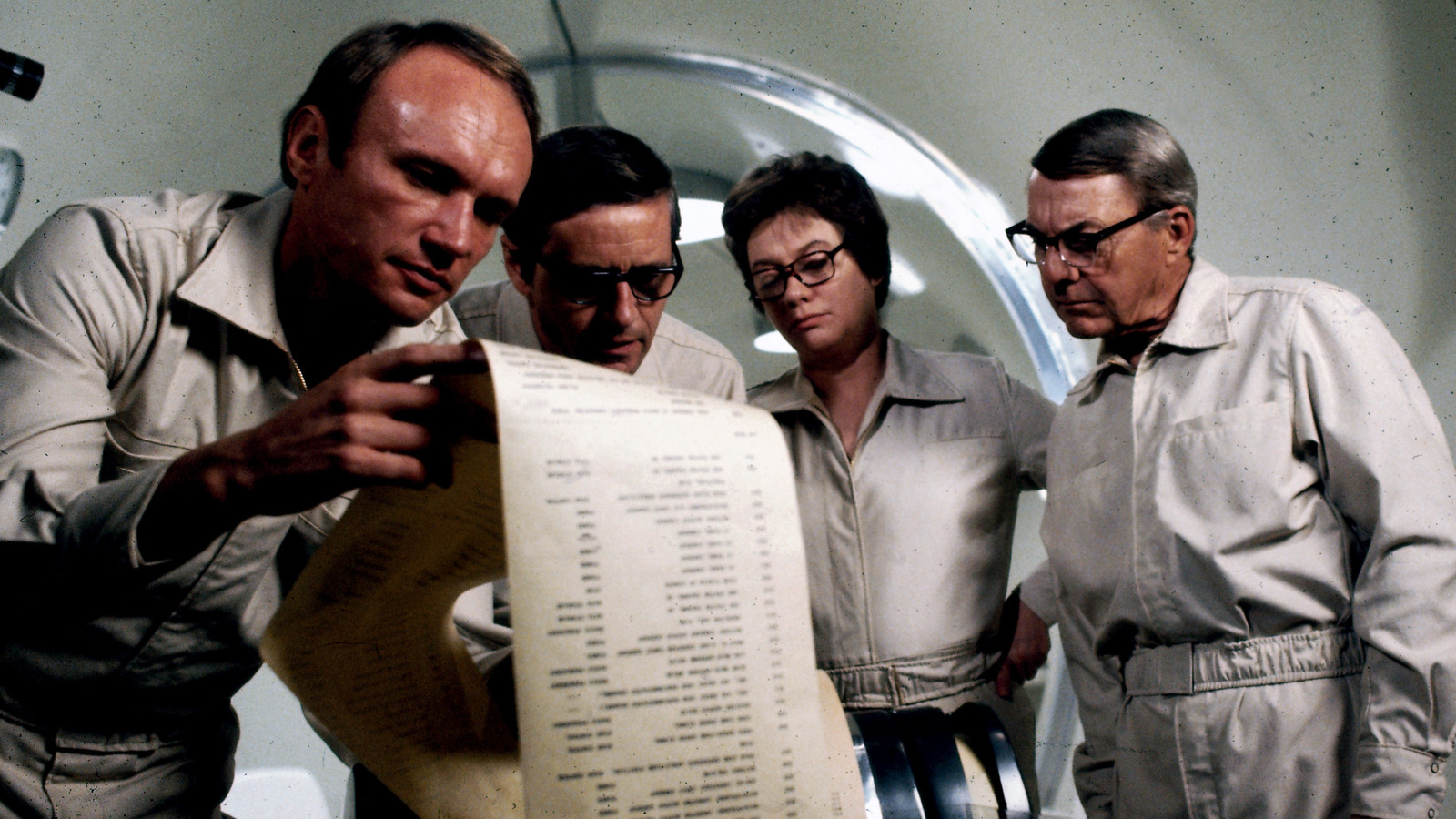

Robert Wise is best-remembered as the director of “The Sound of Music” and “West Side Story” and the editor of “Citizen Kane,” but he also made several other great movies. One of the best was “The Andromeda Strain,” a 1971 sci-fi thriller that pulled off something oft-unthinkable even to this day: employing cutting-edge visual effects in service of a story that didn’t remotely conform to blockbuster standards.

Based on the eponymous novel by “Jurassic Park” author Michael Crichton, who was known for his heavily technical and carefully-researched sci-fi novels, “The Andromeda Strain” is a science fiction movie that places a vanishingly rare amount of emphasis on the science, with a plot that largely consists of experts arguing tensely about the most sensible course of action. And, to be clear, it’s riveting stuff.

Set at the height of Cold War anxieties surrounding biological warfare, the movie chronicles the efforts of a scientist team to isolate and analyze the area of a New Mexico town, in which nearly the whole population died following a satellite crash. While carefully investigating the nature of the life form that laid waste to the town, the scientists are faced with a terrifying question: Has their own facility already been contaminated? A close-quarters thriller of uncommon intelligence and tautness, “The Andromeda Strain” also pioneered the use of optical photographic VFX. In other words, it was ahead of its time both technically and narratively — an early-’70s film that feels startlingly, impossibly modern when watched today.

Ivan Vasilyevich Changes His Profession

When seen in 2025, the 1973 Soviet megahit “Ivan Vasilyevich Changes His Profession” aptly demonstrates that great comedy is ageless and universal, even when steeped in the culturally and politically specific. Directed by Leonid Gaidai and scripted by himself alongside Vladlen Bakhnov, “Ivan Vasilyevich Changes His Profession” adapts the play “Ivan Vasilyevich” by Mikhail Bulgakov, completed in 1936 but not allowed to be published or performed until the 1960s. And, much like the play, it’s a fierce yet buoyant work of political satire.

The hilariously dry title refers to the accidental bringing of Ivan IV Vasilyevich, a.k.a. Ivan the Terrible, to then-modern-day Moscow. After engineer Aleksandr “Shurik” Timofeyev (Aleksandr Demyanenko) builds a time machine in his apartment, it ends up sending his building’s superintendent Ivan Vasilyevich Bunsha (Yury Yakovlev) and burglar George Miloslavsky (Leonid Kuravlyov) into the 16th century, while the most infamous tsar in Russian history (also played by Yakovlev) gets yanked into the present. He just so happens to look exactly like the superintendent — starting a series of farcical, increasingly absurd misunderstandings as Shurik scrambles to fix the machine.

Naturally, it’s a movie that pokes fun at Soviet politics and history, drawing whip-smart humor from the efforts of a stuffy 1970s state bureaucrat to pass as a medieval tyrant. But “Ivan Vasilyevich Changes His Profession” is also witty and thoughtful enough to remain hilarious even decades removed from its original context, and even for Westerners who don’t know the first thing about Russia.

Zardoz

Sometimes, it’s not until the dust has settled on a movie’s initial reception that its real, enduring value can be ascertained. Such is the case of “Zardoz,” the notorious 1974 John Boorman sci-fi blockbuster that got initially written off as a critical and box office failure — before being rehabilitated, over the decades, by a growing contingent of devoted aficionados.

“Zardoz” followed Boorman’s failed attempt to bring “The Lord of the Rings” to the big screen and teems with passion for the lush imaginative possibilities of the film medium. The original, Boorman-written plot is a kooky post-apocalyptic saga: In the year 2293, some humans have become immortal and sequestered themselves in the insulated, ennui-filled “Vortex,” while mortals — known as “Brutals” — fight for survival in the wasteland that has become of the rest of the Earth. Sean Connery plays Zed, a Brutal trained to kill other Brutals at the orders of the stone idol Zardoz; through a series of circumstances, Zed winds up in the Vortex, where he becomes a key player in ongoing political upheaval.

Like many cult classics, it’s a film to which a conventional critical lens doesn’t necessarily do justice. Audiences at the time didn’t take to “Zardoz,” while reviewers wrote it off as goofy, weird, and awkwardly-paced. But it’s those very offbeat qualities that now make this bizarre Sean Connery sci-fi movie a self-evident high point of ’70s fever dream cinema. It’s a dreamy, unique, breathtakingly gorgeous work of neo-surrealism that operates by its own fascinating rules.

God Told Me To

Sometimes titled “Demon,” “God Told Me To” is a highly eccentric 1976 film that showcases Larry Cohen’s knack for making movies that nobody else could. Like many a Cohen production, it’s hard to classify in terms of genre, hovering somewhere between horror, sci-fi, crime investigation, political suspense, and frantic street-level action. Also like much of Cohen’s work, it didn’t get the attention it deserved originally, opening to mixed critical reception and poor box office, but has since become a highly-reputed cult favorite.

It’s entirely possible that audiences in 1976 just weren’t ready for what a liberated, forward-thinking mélange of moods, styles, and genre conventions “God Told Me To” is. Nor, for that matter, did viewers at the time necessarily know what to make of Cohen’s proudly emotional approach to exploitation, in which the histrionic excess is always laced with poignancy.

“God Told Me To” follows a detective (Tony Lo Bianco) who begins to investigate a series of gruesome murders — including multiple mass killings — committed by individuals who insist that God told them to do it. As morbidly intriguing as that premise is, Cohen also wrings it for all the sincere drama it can offer. And then there’s the matter of the tenacity and creativity with which he lays out his elaborate thriller across real, gritty New York City locations, creating a sprawling urban epic that feels rooted in everydayness even as the sci-fi elements take over. Few ’70s movies are so mesmerizing to watch nowadays.

The Visitor

The ’70s were a golden period for strange, indefinable psychedelia that spoke directly to the brain’s sensory response centers. This was also true of sci-fi cinema, which saw a rise in movies where speculative technology and made-up machinery worked as extensions of the overarching non-logic, and interplanetary contact served as an excuse for boundless absurdity. Within that context, it’s no surprise that the decade was bookended by “The Visitor.”

This 1979 Giulio Paradisi-directed film, also often known by its original title “Stridulum,” puts the lie to the idea that ’70s Italian horror began and ended with giallo. While there are echoes of giallo in its bright colors, gruesome violence, and feverish tone, “The Visitor” is sci-fi horror of the weirdest, and therefore highest, order. The plot concerns a cult determined to bring back Zatteen, an ancient malevolent cosmic force, by channeling him into a human child. It’s up to Jerry Colsowicz, an alien emissary with telekinetic powers, to stop their plans.

If that all sounds corny, that’s because it is: As a work of organized storytelling, “The Visitor” is messy, derivative, overfussy, and hard to get a grip on. But, as pure cinema, it’s fantastic, a succession of images and plastic ideas so beguiling that there hardly needs to be a throughline connecting them. At the time, it probably seemed to viewers like little more than a “Rosemary’s Baby” clone; now, it’s hard to care about anything other than its visuals, which carry an ineffable, almost transcendent power.

Quintet

“Quintet” is one of the most critically reviled movies of Robert Altman’s career. It’s also, depending on who you ask, one of the best, and maybe the single most benefited by hindsight. If made today, with similar directorial prowess and the same level of star power and acting talent, “Quintet” would probably be deemed a tough, challenging, wilfully impenetrable, but nonetheless vital work from a master reaching beyond his comfort zone. In 1979, it was deemed a turkey.

Even as a turkey, “Quintet” presented such an indelible new vision for sci-fi cinema that it laid the groundwork for a lot of the genre’s modern offerings. There’s an abstract, minimally-teased-out plot about a seal hunter (Paul Newman) crossing a barren post-apocalyptic tundra and ultimately finding himself in a hotel where bored rich people are playing a board game with life-or-death stakes. But Altman scarcely concerns himself with the plot. He’s interested in the epic snowy landscapes, the societal breakdown, the pervasive sense of helplessness and isolation, and the (highly prescient) theme of humans’ failure to do right by their planet.

Critics at the time lambasted the movie for its efforts at profundity and its so-called pretentiousness and self-importance, and audiences responded in kind by not turning out to see it. But there’s something fundamentally riveting about Altman making a stark, atmospheric arthouse sci-fi drama that lets big ideas fill the silences and the vast spaces. About half a dozen cinephile-darling contemporary directors could have their work traced back to “Quintet.”