Share and Follow

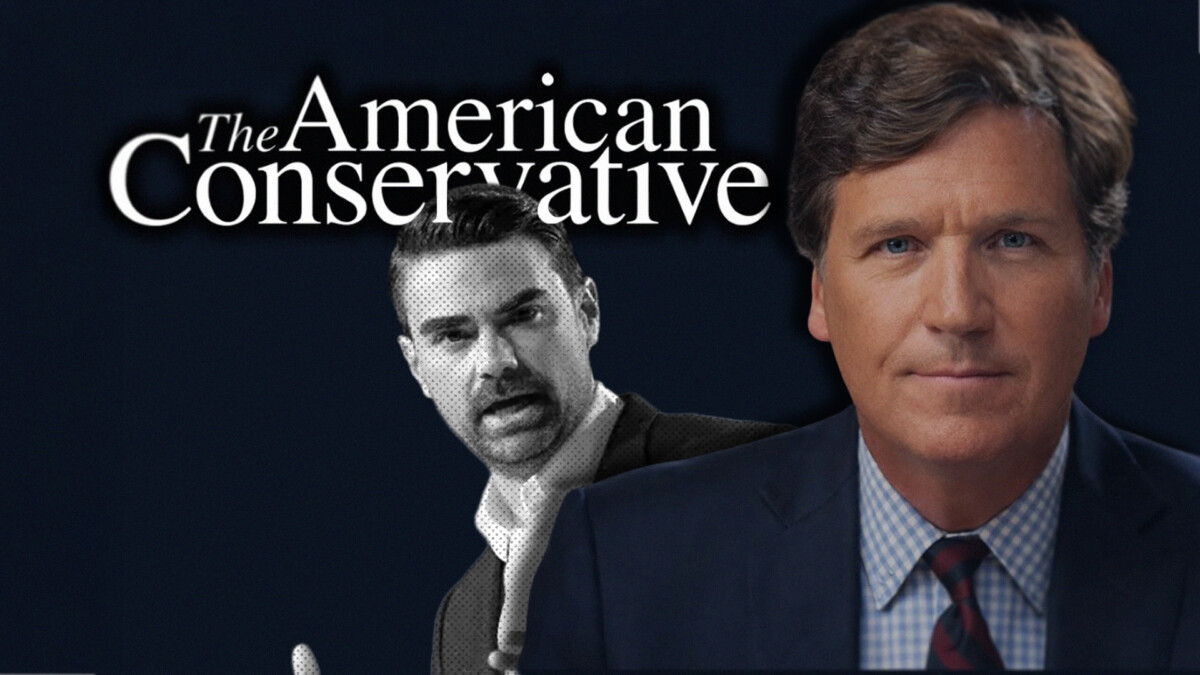

In a interview with The American Conservative’s Harrison Berger, Carlson ties the core of Western civilization to the Christian belief in the individual human soul, arguing that any politics built on hating entire groups—Muslims, Jews, or anyone else—betrays both Christianity and the West.

He critiques figures like Ben Shapiro and Jonathan Greenblatt, accusing them of inciting group-based anger. He chooses not to engage with what he terms “hate bait” and encourages conservatives to evaluate individuals on their own merits to maintain moral clarity and cohesion.

Muslim hate vs. anti‑Semitism: TPUSA speech and Christian basics

Harrison Berger begins by likening Carlson’s recent speech at a TPUSA event to a call reminiscent of Martin Luther King Jr., advocating for judging people as individuals “as God would,” rather than as representatives of a group. Carlson explains that his speech wasn’t pre-planned but rather an expression of his current thoughts, including the rise of rhetoric that labels all Muslims as adversaries. He questions, “How is hating all Muslims better than hating all Jews?” and labels such sweeping hatred as “disgusting.”

Carlson firmly believes that Christians have no justification for harboring hatred against entire groups. “Christians aren’t supposed to hate anybody,” he asserts, while acknowledging his own past personal animosities. The key principle, he emphasizes, is to assess behaviors on an individual basis rather than by group affiliation. Punishing children for their parents’ actions crosses a boundary that undermines justice, he argues.

He further explores the topic of “Western civilization” often discussed by right-wing commentators. Carlson contends that the essence of the West lies not in economic metrics like the free market or GDP, but in “the belief in the individual human soul,” a concept deeply rooted in Christianity. This belief opposes collective punishment and group animosity and, according to him, sets the West apart from “non-Western societies” that prioritize clans and groups over individuals.

Hiroshima, Gaza and the erosion of moral boundaries

Carlson reveals to Berger that his remarks at TPUSA, particularly about the “erosion of moral boundaries” during conflicts as “disgusting and immoral,” provoked strong backlash from Shapiro and like-minded conservatives. He clarifies his stance, stating, “If indiscriminately bombing children is wrong in Hiroshima, it’s equally wrong in Gaza.” This perspective led to accusations of betrayal and more from critics.

He argues that the anger from his critics shows they do not really believe in individual souls at all. To justify mass killing of civilians, he says, “you have to believe… they’re subhuman,” and that assumption is “the only reason they’re comfortable” with the images coming out of Gaza as long as they fit their narrative. This, he continues, is a “non‑Western view” that obsesses over group identity and treats whole populations as either guilty or expendable.

Carlson links this mindset with both anti‑Semites and ethno‑nationalist hawks. He notes that both anti‑Semites and ethno‑narcissists fixate on Jews in the same way; they only disagree over whether Jews are villains or heroes. What they share is an obsession with groups rather than persons. For Carlson, that is the opposite of what Christianity demands.

He also describes the personal fallout from his stance: lost friendships, subscription cancellations and a flood of attacks labeling him a “Nazi.” Instead of responding in kind, Carlson says he has started to pity some of his fiercest critics. He points to Shapiro’s own admissions about heightened security and says bluntly that if you “wear a bulletproof vest in private” and live in constant fear, “you live in hell.” In Carlson’s telling, people in that condition are not moral guides; they are warning signs of what unchecked hatred does to the soul.

Rejecting dual loyalty myths and the ‘hate bait’

Berger notes that anti‑Semites like Nick Fuentes and hardline Israel‑first figures like Mark Dubowitz both push dual‑loyalty narratives—Fuentes claiming Jews secretly care only about Israel, Dubowitz urging Jews to flee to Israel in response to Western antisemitism. Carlson agrees and says plainly that in practice they are making “the same arguments,” merely from different angles. Both crowd politics around a single group and tell everyone else to define themselves in relation to it.

As a non‑Jew, Carlson says he is “not obsessed with Jewishness” and refuses to make any group, Jewish or Muslim, the center of his moral universe. He emphasizes again that anti‑Semitism is “immoral” in Christian teaching, but adds that the principle is universal: the same rule applies to hatred of Muslims, whites, blacks, or any other category.

Carlson argues that public figures like Shapiro and Greenblatt are not simply reacting to hatred; they are, in many cases, trying to manage and weaponize it. By smearing critics as Nazis and bigots, he says, they hope to “control your emotions,” much like a dysfunctional spouse who deliberately provokes fights to gain leverage. The goal of this strategy is to increase anger and fear, not resolve it.

He calls this dynamic “hate bait” and warns his audience not to bite. The entire point, he says, is to entice conservatives into becoming the caricatures their enemies already describe—seething anti‑Semites, seething Muslim‑haters—and thereby justify more censorship and repression. “Why would I let that person set the terms for me?” he asks, referring to his most vocal critics.

Christianity vs. the identity trap

Carlson closes the interview by focusing on what this means for the future of the right. He says he has become “calmer” and “less angry” as he has consciously refused to let hatred take root, especially with “too many children” and responsibilities depending on him. In his experience, “haters” are “always destroyed by it,” whether their obsession is race, religion or politics. He is not willing, he says, to sacrifice his soul or his family to join that club.

He warns that both anti‑Semitism and across‑the‑board Muslim hate are being deliberately stoked as tools to “increase the hatred,” splinter conservatives and turn them against each other so entrenched elites can grab more power.. The antidote, in his view, is a return to Christian first principles: refuse to hate entire peoples, refuse collective guilt, and insist on seeing each person as an individual soul before God.

For Carlson, this is not a soft or sentimental stance; it is a hard boundary. Either conservatives reclaim that soul‑based understanding of the person, or they slide into the same identity‑driven politics they once opposed. His message is stark but hopeful: do not let your enemies, or your supposed allies, turn you into a hater; decide what is at the center of your life “as a free man,” judge people as individuals, and rebuild unity on that ground—or watch the movement, and the country, fracture along lines of fear and revenge.