Share and Follow

Mara Berton and June Higginbotham, like many young women, dreamed of starting families and becoming mothers from a young age. However, as a lesbian couple, they faced obstacles in accessing fertility treatment insurance benefits that were readily available to their heterosexual counterparts.

Residing in California, Berton and Higginbotham found themselves having to spend $45,000 out of their own pockets to conceive, while heterosexual colleagues under the same insurance plan enjoyed coverage for many of these costs.

“We knew it wasn’t right,” Berton shared in an exclusive conversation with CalMatters. Motivated by this disparity, she became part of a class action lawsuit challenging the discriminatory policy. “What we’re fighting for is about family building and having kids… It was really important to both of us that other couples not have to go through this.”

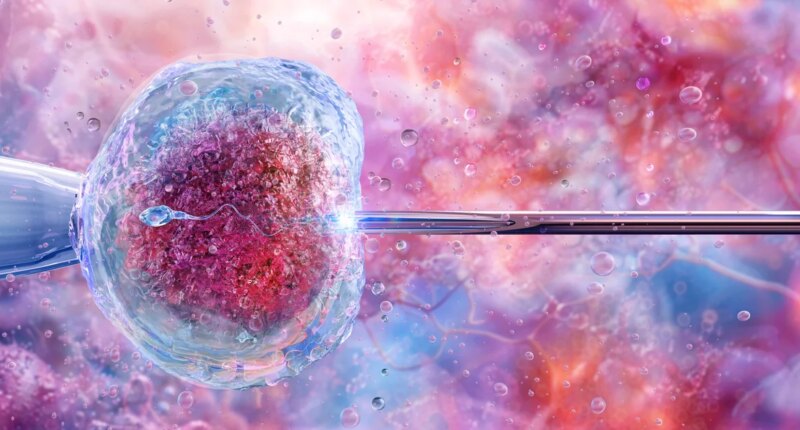

In a groundbreaking development last week, U.S. District Judge Haywood Gilliam Jr. from the Northern District of California approved a preliminary settlement for the lawsuit. This agreement mandates Aetna to extend fertility treatment coverage, including artificial insemination and in vitro fertilization, to same-sex couples, aligning it with the benefits available to heterosexual couples. This marks the first instance where a health insurer is required to implement such a policy nationwide, benefiting an estimated 2.8 million LGBTQ members, including 91,000 in California.

Additionally, the settlement stipulates that Aetna will pay a minimum of $2 million in damages to eligible members based in California. Those who qualify have until June 29, 2026, to submit their claims.

“I truly hope that this is the first of many insurers to change their policy,” said Alison Tanner, senior litigation counsel for reproductive rights and health at the National Women’s Law Center. “We were looking at that as an issue of inequality — that folks who were in same-sex relationships were being treated differently.”

Roughly 9 million additional Californians will soon have access to mandated fertility benefits under a new law taking effect in January. The law applies to state-regulated plans — which Aetna is not in this case — and amends the definition of infertility to include same-sex couples and single people.

Previously, Aetna’s policy required enrollees to engage in six to 12 months of “unprotected heterosexual sexual intercourse” without conceiving before qualifying for fertility benefits, according to the class action complaint. The policy allowed for women “without a male partner” to access benefits only after undergoing six to 12 cycles of artificial insemination unsuccessfully depending on age.

Lawyers argued that the policy fundamentally treated LGBTQ members differently and effectively denied them access to the benefit, which can be prohibitively expensive for many people.

In an email, Aetna spokesperson Phillip Blando said the plan provides infertility benefits in accordance with each member’s plan, coverage rules and applicable law.

“Aetna is committed to equal access to infertility coverage and reproductive health coverage for all its members, and we will continue to strive toward improving access to services for our entire membership,” Blando said.

Berton, who was the lead plaintiff in the case, said she was blindsided by the policy. She had consulted with a fertility clinic and decided to move forward with donor sperm and artificial insemination, when a representative from Aetna called and said she did not meet the definition of infertility.

She appealed the decision multiple times; she was rejected. The experience felt “dehumanizing,” her wife Higginbotham said.

Insurance had dictated Berton attempt 12 rounds of artificial insemination before she would be eligible for benefits. Her doctors recommended no more than four rounds.

Sean Tipton, chief advocacy and policy director for the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, said a policy like that could only be designed to dissuade people from accessing their health benefits. Doctors typically recommend three to four cycles of artificial insemination before IVF, but Tipton said there have also been studies showing it is more efficient and cost effective to go straight to IVF.

In 2023, the society updated its medical definition of infertility to include LGBTQ folks and individuals who don’t have partners. They did so in part to stop insurers from denying claims like Berton and Higginbotham’s.

“The driving force was a realization that it takes two kinds of gametes to have kids,” Tipton said. “Regardless of the cause of that absence, you have to have access in order to be treated for a fertility issue.”

Ruslanas Baranauskas/Science Photo Library

Since the definition changed, Tipton said more employers and insurers are covering benefits for LGBTQ folks or single people. They have also leveraged the definition to enact statewide benefits expansions, including California’s upcoming fertility benefits mandate.

Berton and Higginbotham said they also worried about running out of donor sperm that matched Higginbotham’s Jewish and Native American heritage — and was limited in supply.

“I don’t feel like your insurance should be involved in those types of decisions and kind of determine your journey,” Berton said.

The couple pulled together money from family members and decided to proceed even without coverage. After four unsuccessful rounds of intrauterine insemination, they moved on to IVF, partially to give themselves the best chance of conceiving with the donor they chose.

The experience was “all consuming” and emotionally difficult as Berton endured hormone injections, egg retrievals and a miscarriage. But today, she and Higginbotham have two healthy twin girls whose favorite thing is to play on the swings and “take every book off of their shelf” for their mothers to read.

The couple achieved their family dreams before the lawsuit concluded. Even so, Higginbotham said she hopes the settlement will help other LGBTQ couples across the country.

“I know people that don’t have children, that wanted children, because the stuff isn’t covered. I know people that their timeline was delayed and maybe they have fewer kids than they wanted,” Higginbotham said. “The settlement is such a huge step forward that is really righting a huge wrong.”