Share and Follow

In the realm of law enforcement, officers have traditionally been trained to swiftly gain control of chaotic situations by establishing a tactical advantage, often resorting to drawing their weapons. However, there is now a growing movement advocating for alternative strategies that prioritize de-escalation without the immediate use of firearms.

Across the Chicago area, police departments are increasingly adopting training programs that are informed by scientific research. These initiatives aim to equip all officers with the skills necessary to handle intense scenarios in a manner that minimizes the risk of harm to everyone involved, ensuring the safety of both officers and civilians alike.

ABC7 Chicago is now streaming 24/7. Click here to watch

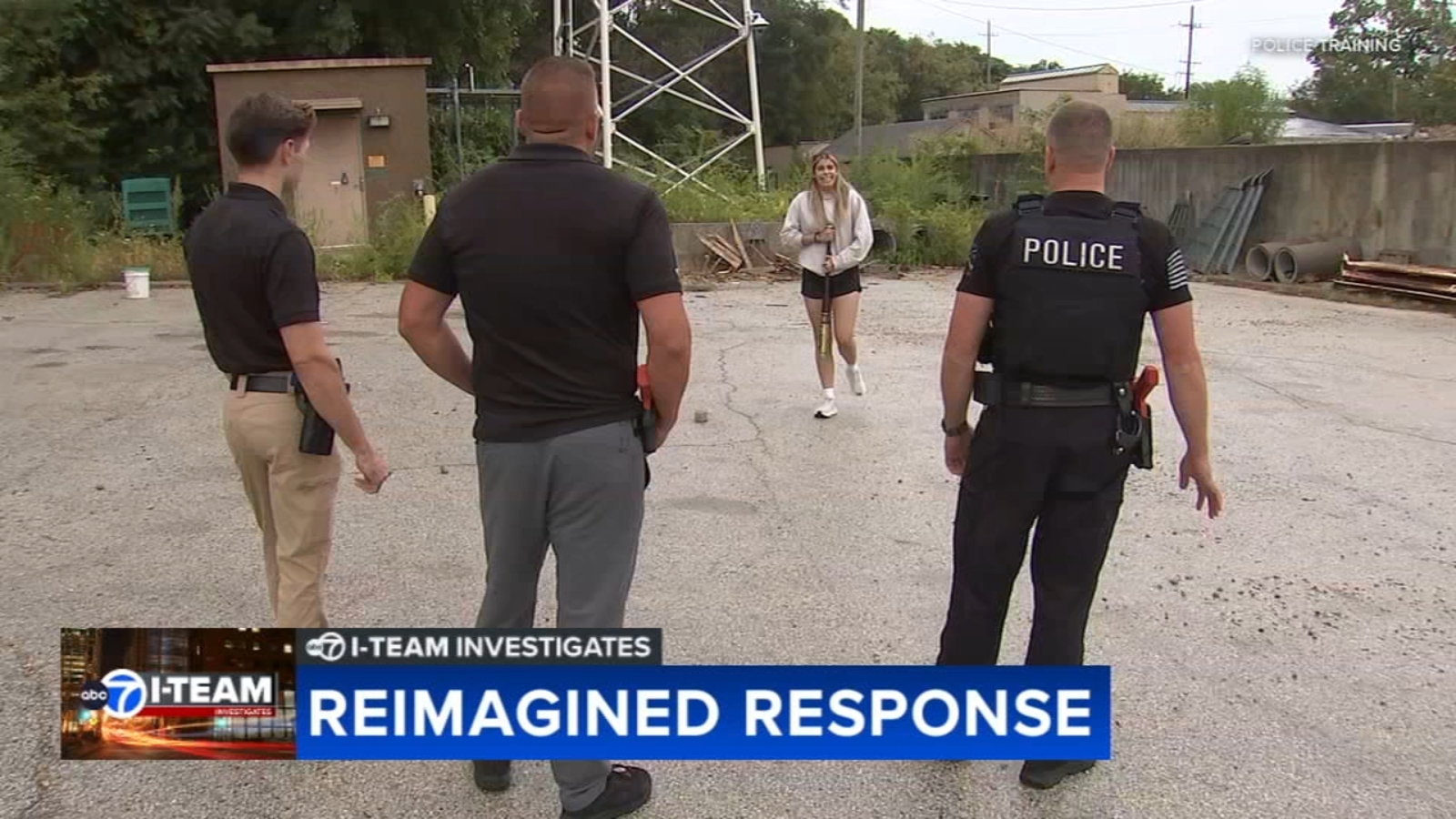

The I-Team had the opportunity to observe one of these innovative training sessions firsthand. Taking place in a sprawling, vacant parking lot, the session was designed to simulate real-life situations in a controlled environment, allowing officers to practice these new de-escalation tactics effectively.

That training is designed to bring everyone home safe, officers and subjects included.

The I-Team was there to watch the scenario-based portion in action as a training session played out in a large empty parking lot.

Officers arrive to find an agitated young woman armed with a metal baseball bat making threatening remarks.

She screamed, “Shut up!”

Those officers keep their distance as they engaged her, asking what happened with her day and expressing empathy for her frustration.

Her response was, “My coach is here, he keeps talking over me. He’s driving me crazy.”

During the exercise, an officer said, “I’d like to get closer to you to talk, but you for me to do that, can you put the bat down?”

There is more back-and-forth as part of the simulation and eventually, she puts the bat down.

Trainers are nearby, coaching officers as they work through the situation.

That scenario is just one of several simulations west suburban officers with the Aurora Police Department completed as part of the Integrating Communications, Assessment and Tactics, or ICAT training.

It is designed to defuse tense situations involving people who are armed with weapons other than firearms.

Just a couple of months ago, officers already trained with the program helped locate and calm a teenager who fled his home at night following a family argument.

Police body camera video captured the response.

After talking with the family about what led up to the conflict, officers used a megaphone to try to get a response from the teen as they tried to locate him.

They said, “It sounds like someone hurt you today,” and, “If we only listened to your mom and didn’t hear what you had to say and we want to talk to you as well, and you could just come out here so we can get your side of it. We would appreciate it.”

Officer Joel Clausing with the Aurora Police Department was there on the scene and was able to use the ICAT training during that call to service.

“This is the best way to prepare myself for dealing with the real human, is to deal with the human role player,” said Clausing.

ICAT is designed for a wide variety of dynamic situations, including mental health crises.

Gina Schonhoff made a gut-wrenching choice to call police on her then 11-year-old adopted son.

“The times that I’ve had to call, my son was just being very unsafe, or a personal safety was threatened, and so it was a matter of if I don’t call, somebody is likely going to get hurt,” she explained.

Her son has mental health challenges and behavioral issues. But Schonhoff worried about the police response. How severe would they be?

“I don’t want him to have this trajectory, this life of, you know, hospitalizations is one thing… jail or prison time, potentially, as he gets older is a whole different ballgame. And I didn’t want that for him. But yet, when faced with violence towards me, I’m like, I can’t advocate for him if I’m not here.”

Those police calls ended with her family being safe and her son getting the care he needed. But she says it was the tipping point.

“I think I have a whole lot more understanding and compassion for the families that we work with,” said Schonhoff.

She went back to school and got her master’s degree and is now a police social worker with the Aurora Police Department’s Crisis Intervention Unit, or CIU. She now helps respond to calls just like hers saying, “To help families like mine and to just bring awareness of you know the complexities of what families like mine go through.”

While members of that unit already have specialized training, she said the ICAT training for all officers would be invaluable, especially if the crisis unit cannot get to the scene immediately.

The program’s philosophy is to use time and distance to slow things down and lower the temperature in volatile situations.

Officers learn to be active listeners, gathering intelligence about the subject and building rapport before approaching.

David Guevara, an investigator with Aurora Police Department, is also on the crisis team and helps with the ICAT training.

He explained what officers are taught to consider on a call.

“Do we need to be right there in somebody’s personal space, or can we give ourselves some space and talk with them in a different means? Don’t be the reason that you have to use force,” he said.

The urgency for new policing tactics was underscored recently after a former Sangamon County sheriff’s deputy was convicted of second-degree murder in the death of Sonya Massey. She called 911 asking for help over a possible prowler.

Sean Grayson shot Massey after confronting her about how she was handling a pot of hot water.

That shooting prompting a federal probe that resulted in the sheriff’s department agreeing to de-escalation training. The department used the ICAT program.

Some skeptics have long questioned whether the overall philosophy of de-escalation training is effective or safe, citing a lack of evidence.

Robin Engel, Ph.D., is a senior research scientist and a criminology expert at The Ohio State University.

She told the I-Team, “That initial reaction by law enforcement, I think is a legitimate one we hardly ever test training. But in this case, we did test the training.”

Engel and a team of researchers evaluated the ICAT model and said they have proof the program works.

That research shows officer use of force in Louisville, Kentucky was down 28.1%, and use-of-force incidents with citizen injuries decreased by 26.3%.

Injuries to police were down even more, by 36%.

A follow-up study with Indianapolis police also found similar declines.

“The thing about ICAT is, it’s centered around core principles of the sanctity of life, and that sanctity of life is at the core of all decision making… It helps everyone, quite honestly, go home safe at night,” Engle said. “We didn’t realize how strong the impact would be of keeping officers safe along with the subjects that they were interacting with. So that was something that we could finally come back. We had the evidence to say ‘No, this isn’t going to get you killed out there. It’s actually making you safer, and it’s making the subjects you interact with that are the persons in crisis – it’s making them safer, too.’”

Guevara said since Aurora started using the program this past spring, they are seeing a difference on the streets, but he admits the department knows there will be times the approach does not fit the situation, especially if a subject is threatening with a gun.

“You have the ability to do what you can, and we cannot control what a person does. There are times where we may not have a safe outcome. That person may put us in a situation where we may have to use some force. At least I can say, ‘I tried,’” Guevara said.

The teen involved in the August disturbance was located and, without incident, transported to a hospital for evaluation.

“There’s a way we can come to a solution without the police getting hurt, without the subject getting hurt, without citizens getting hurt. That’s what we’re going after and that’s what we can accomplish,” said Clausing.

The Police Executive Research Forum, which developed the ICAT, told the I-Team more than 1,300 law enforcement agencies from across the nation have received ICAT training since its inception 10 years ago.

In Illinois, 80 departments including Chicago police and Illinois State Police are now trained. Click here for more information.