Share and Follow

The 1960 classic movie Breathless by Jean-Luc Godard holds great significance and has had a profound influence on cinema. However, this might not be very evident when watching Richard Linklater’s film Nouvelle Vague, which is a tribute to the French New Wave. Even though it doesn’t delve deep into the historical context, the film presents a charming mix of comedy and drama akin to Linklater’s own works like Everybody Wants Some!! and Dazed and Confused.

Linklater’s admiration for the French New Wave master is not the focal point of the movie. Instead, he takes Godard’s ideas seriously without putting him on a pedestal. Nouvelle Vague focuses more on capturing the fascinating moment of Breathless‘ creation rather than just praising the film itself. While there are visual homages such as effective close-ups, the film maintains a certain distance between the camera and the unfolding events, allowing the incorporation of elements like black and white film stock and a 4:3 aspect ratio.

For those unfamiliar with it, Breathless was groundbreaking in its unconventional approach, introducing techniques like lengthy walk-and-talks and jump cuts, which have now become standard in films. Linklater’s Before trilogy is heavily influenced by Godard, but instead of mimicking his style, Linklater infuses his own unique touch. His portrayal of Godard in the film, played by Guillaume Marbeck, suggests a fictionalized version of the French legend who is somewhat perplexed by the pervasive influence of American cinema that played a significant role in the creation of Breathless.

The result is a hangout movie first and foremost, one that understands that while Godard went on to push the boundaries of cinema right up until his death, his directorial career began with a scrappy independent project that would’ve likely been fun and frustrating to those yet to be convinced of his genius. He was, after all, only 29 when he made his mark, a fact of which Nouvelle Vague never loses sight, with its litany of supporting characters playfully dressing him down.

The movie begins by introducing Godard alongside fellow New Wave enfant terribles Francois Truffaut (Adrien Rouyard), Suzanne Schiffman (Jodie Ruth-Forest) and Claude Chabrol (Antoine Besson), fellow critics for French magazine Cahier du Cinema, who all recently made their directing debuts. Godard is the last of their cohort to take the leap, leaving him to navigate both the labyrinth of film funding and pressures of expectation. However, Marbeck’s droll delivery helps craft a cool, calm and collected Godard, who spouts philosophical quotes from behind his shades, and almost always poses with a cigarette as he saunters across the frame. He’s a mystery of sorts, not unlike James Mangold’s Bob Dylan in A Complete Unknown. Only where Mangold’s camera felt in awe of his central subject, Linklater’s seems more bemused by his youthful gamble.

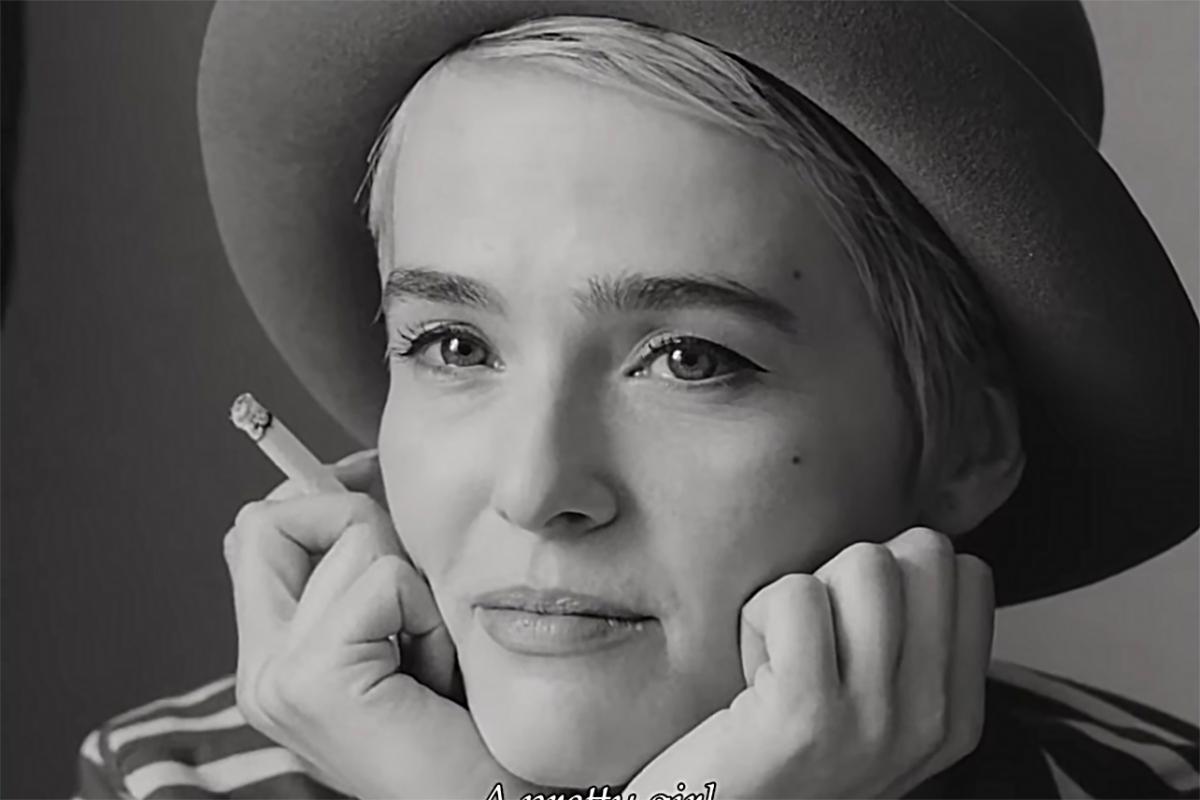

This cautious perspective aligns with that of Breathless actress Jean Seberg (Zoey Deutch), a rising American star whose skepticism and frustration with Godard’s erratic techniques is the heart of Nouvelle Vague’s comedy. On the other hand, her co-lead Jean-Paul Belmondo (Aubry Dullin) goes with flow, convincing her to let loose and give in to Godard’s script-less musings. For Seberg, this experience is one of constant negotiation, and despite having been proven wrong by history, Linklater’s camera never judges her for her misgivings. If anything, when Godard slinks away from set to scribble ideas in his notebook, he seems entirely off his rocker, which is part of the movie’s fun.

From a meta perspective, the question of whether Linklater himself buys into Godard’s madness is equally amusing to unpack. Like any stylistic influence this enormous and omnipresent, it’s hard for a film like Breathless not to seep into one’s creative DNA. In fact, this might even be possible without having ever experienced Godard’s work. Linklater introduces each legend from the era—Varda, Rohmer, Rossellini, Cocteau—with their own individual frame and slug text plucked out of time, like something from a Wes Anderson film (if anything Anderson’s post-modern wonderlands are the true American successor to Godard). However, when it comes to the specific innovations of Breathless, Linklater plays coy, and only employs familiar shots and cuts on special occasions.

When the story begins taking shape in Godard’s mind, we glimpse his signature jump cuts during a car ride (much like in Breathless), and when he finally begins shooting, we’re finally afforded the pleasure of a conversation in a lengthy, snaking wide shot, the kind with which he would go on to capture Seberg and Belmondo. Other than these two moments—in which Godard’s ideas are so potent that they re-shape the image—Nouvelle Vague is mostly constructed from traditional means, with back-and-forth coverage in medium shots that helps establish a wildly enjoyable comedic rhythm.

In fact, if there’s any shot that defines the film’s approach, it’s one of Godard operating a wheelchair as a makeshift camera dolly, moving across the screen in one direction as Linklater’s camera executes a similar shot while moving in the opposite direction, as though he were actively fighting against the tide of Godard’s influence. Regardless, they still briefly meet in the middle, because when you make a movie today, you’re speaking a language Godard practically re-wrote over six decades ago, whether or not you realize it.

Nouvelle Vague may not be enlightening the way Godard’s movies usually were, but that Linklater toys with this language in service of a film about the joys of DIY filmmaking is all the more delightful. He does so while tossing both skeptics and believers in the mix, giving them equal claim to Godard the flesh-and-blood artist, as well as Godard the filmmaking legend, two identities that once existed as pure potential. We might be watching the film from a future vantage, with foreknowledge of how things went, but Linklater beams it to us from the past—from a time where such things were unknowable, and thus, all the more exciting.

Siddhant Adlakha (@SiddhantAdlakha)is a New York-based film critic and video essay writer originally from Mumbai. He is a member of the New York Film Critics Circle, and his work has appeared in the New York Times, Variety. the Guardian, and New York Magazine.

(function(d, s, id) {

var js, fjs = d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0];

if (d.getElementById(id)) return;

js = d.createElement(s); js.id = id;

js.src = “//connect.facebook.net/en_US/sdk.js#xfbml=1&appId=823934954307605&version=v2.8”;

fjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js, fjs);

}(document, ‘script’, ‘facebook-jssdk’));