Share and Follow

The execution of a man in Utah by firing squad was halted by the state’s Supreme Court on Friday after his lawyers contended that his dementia should prevent his execution.

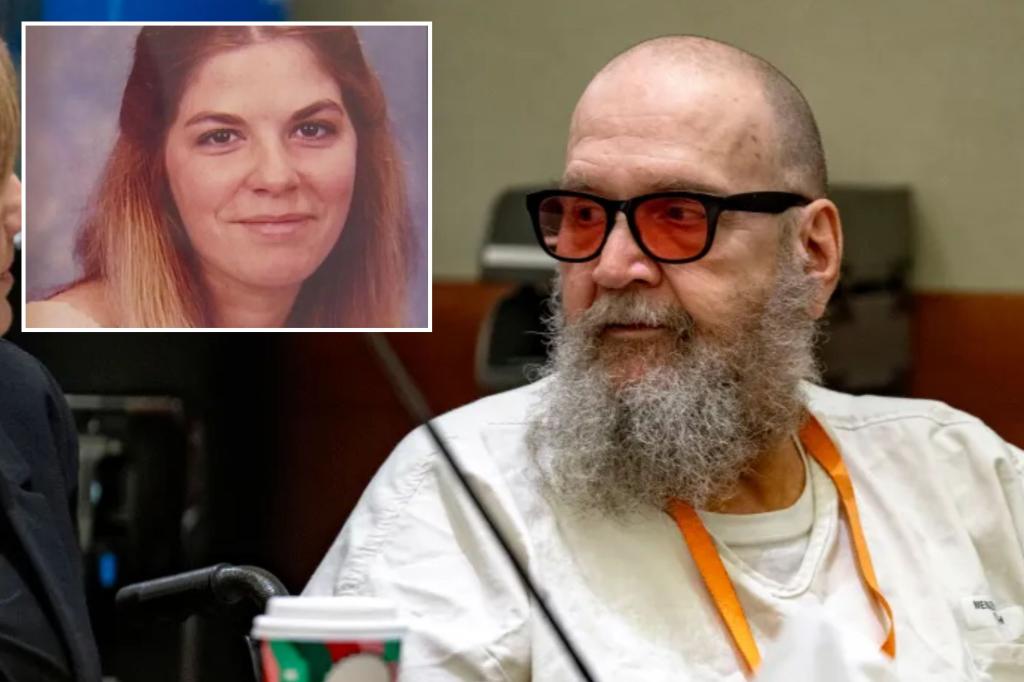

Ralph Leroy Menzies, 67, was set to be executed Sept. 5 for abducting and killing Utah mother of three Maurine Hunsaker in 1986.

When given a choice decades ago, Menzies selected a firing squad as his method of execution.

He would have become only the sixth US prisoner executed by firing squad since 1977.

Attorneys for Menzies initiated a renewed effort in early 2024 to have his death sentence lifted, stating that the dementia he developed during his 37 years on death row is so advanced that he relies on a wheelchair, needs oxygen, and cannot comprehend why he is set to be executed.

The Utah Supreme Court determined that Menzies convincingly demonstrated a significant change in circumstances and presented a compelling question regarding his capacity for execution, leading to a decision that a lower court must reassess his competency.

“We acknowledge that this uncertainty has caused the family of Maurine Hunsaker immense suffering, and it is not our desire to prolong that suffering.

But we are bound by the rule of law,” the court said in the order.

A defense attorney for Menzies said his dementia had significantly worsened since he last had a competency evaluation more than a year ago.

“We look forward to presenting our case in the trial court,” attorney Lindsey Layer said.

In a statement to media outlets, Hunsaker’s family members said they “are obviously very distraught and disappointed at the Supreme Court’s decision” and asked for privacy.

The Associated Press left phone and email messages Friday with a spokesperson for the Utah Attorney General’s Office seeking comment on the ruling.

Menzies is not the first person to receive a dementia diagnosis while awaiting execution.

The US Supreme Court in 2019 blocked the execution of a man with dementia in Alabama, ruling Vernon Madison was protected against execution under a constitutional prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment.

Madison, who killed a police officer in 1985, died in prison in 2020.

That case followed earlier Supreme Court rulings barring executions of people with severe mental illness.

If a defendant cannot understand why they are dying, the Supreme Court said, then an execution is not carrying out the retribution that society is seeking.

Medical experts brought in by prosecutors during hearings into Menzies’ competency said he still has the mental capacity to understand his situation.

Experts brought in by the defense said he does not.

Hunsaker was abducted from a store Feb. 23, 1986.

She later called her husband to say she had been robbed and kidnapped but that she would be released by her abductor that night.

Two days later, a hiker found her body at a picnic area about 16 miles away in Big Cottonwood Canyon. Hunsaker had been strangled, her throat slashed.

Utah’s last execution played out by lethal injection a year ago.

The state hasn’t used a firing squad since the 2010 execution of Ronnie Lee Gardner.

Earlier this year, South Carolina executed two prisoners by firing squad.