Share and Follow

As Colorado River stakeholders scramble to negotiate the basin’s long-term operational guidelines, the Trump administration is expressing support for a state-level consensus agreement while warning that federal officials will step in if necessary.

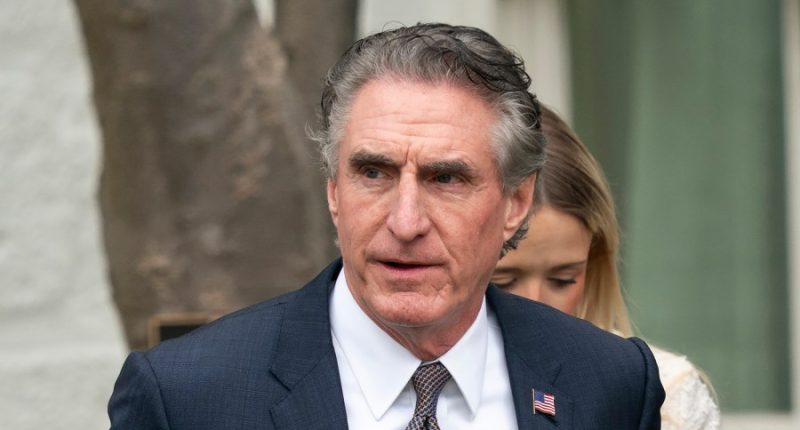

A message relayed on behalf of Interior Secretary Doug Burgum on Thursday indicated that his department would “be intensely, consistently and constantly involved in discussions with the representatives of the seven basin states to forge a path forwarded together on the Colorado.”

“He really wants to have the department help you arrive at a seven-state solution,” Scott Cameron, senior adviser to Burgum, told Colorado River commissioners from Colorado, Wyoming, Utah and New Mexico.

“Having said that, though, in the, we hope, highly unlikely and unfortunate event that there is no seven-state agreement, then he is prepared to act,” Cameron said of Burgum.

Cameron was participating in a meeting of the Upper Colorado River Commission, which convened to discuss ongoing negotiations over the artery’s future, as well as shorter-term hydrological matters.

The seven basin states have been engaging in intense negotiations for more than a year over an update to the river’s interim guidelines, which were set in 2007 and expire at the end of 2026.

Key differences have persisted among the Upper and Lower Basin states Arizona, Nevada and Californiaas federal environmental review deadlines loom near.

While the Lower Basin has prioritized shared cuts across the watershed, the Upper Basin has favored a plan that reflects the dynamic hydrological conditions of a region reliant upon mountain snowpack.

The final rules, which must also receive the Interior Department’s approval, will steer conservation policies for a 1,450-mile river that serves about 40 million people in the U.S. and Mexico.

“I urge you to continue to work with your commissioners and give them the freedom of maneuver to strike an appropriate deal so that all seven states can move forward on your own terms,” Cameron said on Thursday.

In his role as adviser to Burgum on Colorado River issues, Cameron told the Upper Basin commissioners that he had received “consistent direction” from the secretary.

Among the secretary of the Interior’s Colorado River responsibilities includes the role of “water master” of the Lower Basin, through which the secretary has the power to allocate surpluses and shortages in that region as confirmed in multiple court decisions.

While the secretary has no such powers in the Upper Basin, there are multiple federally owned and managed water storage and transport facilities across the Colorado River system.

Cameron said that Burgum charged him with getting heavily involved in the negotiations by working “intensely to help the states come to a seven-state solution but let him know if he has to act.”

“That’s certainly not his preference at all, but he’s prepared to follow through on his responsibilities if necessary,” Cameron added.

As far as the upcoming federal deadlines are concerned, Cameron highlighted the need for an environmental impact statement (EIS), explaining that his team is framing a draft of alternatives that is broad enough to “address virtually any conceivable seven-state deal that might arise.”

The Interior Department, he continued, hopes to receive confirmation of a seven-state consensus by November 11 and intends to publish a draft EIS by December, kicking off a requisite public comment period.

If the seven states submit the details of their consensus-based proposal by “Valetine’s Day of 2026, February 14,” Cameron said he plans “to essentially parachute in a seven-state deal as the preferred alternative” into a March 2026 EIS.

“We would anticipate the record of decision being in May or June of 2026,” he added.

Adherence to these deadlines, Cameron explained, would enable the implementation of new operational regimes for the Colorado River’s two major reservoirs, Lake Powell and Lake Mead, whose respective water years begin on October 1 and December 1.

Progress cannot necessarily wait until the last minute, as related federal legislation must pass through Congress and then head to President Trump’s desk, while some states have similar requirements in their own legislatures, Cameron noted.

“If you can’t get there, Secretary Burgum is prepared to exercise his authority,” he reiterated.

Nonetheless, Cameron also revealed that the Trump administration was willing to supply funding that might be necessary to advance negotiations.

“We’ve been carefully husbanding available federal cash from the Inflation Reduction Act and the bipartisan infrastructure law in case some of that might be needed to seal a seven-state deal,” he said.

In addition, under the Interior secretary’s federal Indian trust responsibility — through which the U.S. must fulfill fiduciary obligations to protect treaty rights Cameron said that the administration has been engaging with the region’s 30 tribal nations, some of whom have senior rights to water.

Emphasizing that there is “a lot less water in the Colorado system than people thought there was going to be 100 years ago,” Cameron identified “a new hydrologic reality” and a need to “behave differently.”

He spoke with members of the Upper Colorado River Commission just days after news emerged that the seven basin states might be coming to terms with a brand-new proposal centered on “natural flows,” as originally reported by KUNC.

The new plan would allocate Colorado River water deliveries to each basin by taking a three-year rolling average of the amount of water that would flow if dams and diversion infrastructure didn’t exist, according to KUNC.

The possibility of such a proposal first came to light last week at a meeting of the Arizona Consultation Committee, which Cameron also attended.

At the meeting, Tom Buschatzke, director of the Arizona Department of Water Resources, said his state was “evaluating a supply-driven concept that shares the water that the river actually provides while requiring each basin to take actions, to live within their respective shares.”

“The concept maintains an Upper Basin delivery obligation for the Lower Basin,” he added.

Releases for the current water year would be derived from the average “natural flow” of the three preceding years with the releases occurring according to a fixed, yet to be determined, percentage of that flow, Buschatzke explained.

“It is still just a concept,” he said. “We haven’t agreed to anything at this point, but we agreed to test it.”

As these evaluations occur, Buschatzke noted that he was now “more optimistic” that the two basins might be able to come to a consensus and thereby avoid potential litigation.

At the Upper Colorado River Commission meeting on Thursday, Becky Mitchell the group’s chair and Colorado’s lead negotiator likewise confirmed that “the basin states have been exploring an explicit supply driven operational framework based on the natural flow of the river.”

Mitchell said that the suggestion came from the Lower Basin and was framed “as a divorce” that could give each contingent an opportunity to manage their supplies independently.

“We must move to a supply-based approach, and this natural flow could provide a potential opportunity to do that,” Mitchell said.

She emphasized, however, that a natural flow strategy would need to be “used appropriately” and include some flexibility to make adjustments if hydrological conditions worsen.

Deviating from Buschatzke’s proposal, Mitchell stressed that this “conscious uncoupling” arrangement “must not impose a delivery obligation on the Upper Basin under any context.”

At the same time, she described this moment as “the precipice of a major decision point,” which she also characterized as “an opportunity point.”

“We owe it to ourselves to consider how we got here,” Mitchell said. “Today, we stand on the brink of system failure.”

“We have the responsibility and opportunity to do better if we collectively choose to do so,” she added.